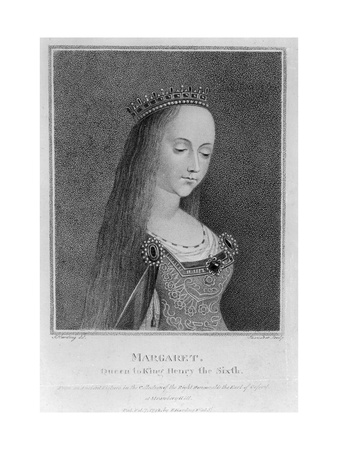

Margaret of Anjou should have had it all. Her husband, King Henry VI, was in her possession. She had a massive army and the road was now clear to London. But what she hadn't reckoned upon was the Londoners.

From their point of view, the hard won Act of Accord had ended the brutal Wars of the Roses. Then their foreign queen had broken the peace. Moreover, she'd done so with a massive army of Scots! (England and Scotland had spent several centuries fighting each other by this point.)

Said Scottish army had been looting and pillaging their way south of the River Trent (as per the agreement hashed out between Margaret of Anjou and Mary of Guelders). And now the queen wanted to lead her Scottish army into London.

She found the gates barred against her. King in tow or not, she was NOT bringing a huge Scottish army into England's capital city.

Margaret didn't have the supplies for this. She could not camp outside London's walls for weeks on end. As she began the withdrawal north, towards the city of York, much of her army realized that the game was up. They broke away and marched back over the border, taking their plunder with them.

Meanwhile, the two bodies of the Yorkist army, headed by Edward and Warwick respectively, joined forces. When they appeared at London's gates, they found them opened wide.

The Earl of Warwick strode into Westminster and proclaimed his teenage companion to be their rightful monarch. Though it was only five months since Parliament had refused to support the same declaration from Richard, Duke of York, the nobles were more amenable to the idea this time.

Which gives a measure of just how upset they were over Margaret's actions.

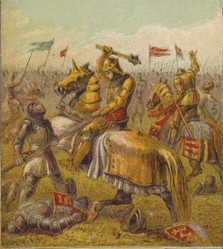

Hurriedly crowned Edward IV, the eighteen year old Plantagenet wasted no time in summoning the full strength of southern England to fight for him. Fully aware that this was going on, Queen Margaret was doing the same in the north, on behalf of Henry VI.

King Edward led his forces north in terrible weather. He'd managed to attract around 30,000 men. Already in Yorkshire, the House of Lancaster got to choose the site of the battle. Approximately 35,000 men turned out for Henry. They took the high ground near the village of Towton and waited.

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Comments

Thank you for reading it, and I'm glad that you liked it. I did hesitate about where to top. Sticking Towton in the middle there just seemed wrong. But there are natural stopping points, when whizzing through all of the Wars of the Roses. I went with the history, not the sentiment.

Yes, I plan to have another two in this series. The next round will be the challenge of the Duke of Clarence, with Warwick.

I've finally had the chance to read this through all the way and I'm glad I didn't rush it. It's a perfect second part to the story. I wondered whether you'd stop at Edward becoming Edward IV so was really glad you didn't.

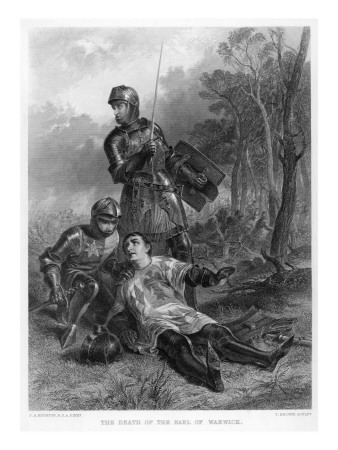

Are you planning on writing anymore about the subsequent battles? I'd love to read a piece by you on Richard Neville's betrayal and his death, along with the Battle of Tewksbury (why can I not spell that right now?)

Of course! This wild ride is all inclusive, jump on!

Thank you very much. <3

500 Wizzles! Woo hoo! GO GIRLFRIEND!!! Can I come along for the ride?

PLLLEEEAAASSEEE!! Take me with you!!! :)

Thank you very much! *blush*

Brilliant article - you really make it come alive! Well done on the EA! You worked so hard. Thanks for this. :)

Gettysburg is the most famous US battle; Antietam was the most deadly. The amount of Americans who died in Maryland that day is truly staggering. Yet still doesn't come close to Towton.

I've seen a parhelion! Ironically, it was while my friend and I were walking around the site of the Battle of Shrewsbury. It's a really, really weird thing to spot. It makes the hair on your arms stick up with sheer weirdness.

I felt that knowing what it was. Imagine those poor Welsh archers at Mortimer's Cross...

Thank you very much for reading my article. <3

A fantastic 500th article! I have almost zero focus today, I'm a bit hyper at the moment so it took me a minute to get through it all >.> But I did!

I found the three suns bit really interesting, I didn't know that could even happen!

The battle of Gettysburg is one of the deadliest in the US right? You used in in comparison with another which I don't think I am familiar with, when talking about the battle Towton.

Congrats on the Editor's Choice!!! And congrats on 500 articles and all of your hard work! <3

Thank you very much. I've been celebrating with a couple of tipples. I nearly choked on it, when I saw the Editor's Choice Award. :)

Congrats Jo, so very well deserved :)