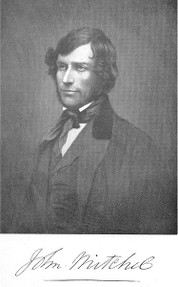

In 1861, Young Irelander John Mitchel wrote a pamphlet. In it, he stated that, 'Ireland was actually producing sufficient food, wool and flax, to feed and clothe not nine but eighteen millions of people'.

In 1861, Young Irelander John Mitchel wrote a pamphlet. In it, he stated that, 'Ireland was actually producing sufficient food, wool and flax, to feed and clothe not nine but eighteen millions of people'.

Furthermore, he contended that every ship bringing a cargo of food relief for the starving masses, would meet another six ships packed with food exports on the way out of the same harbours.

His most famous line was his conclusion: 'The Almighty, indeed, sent the potato blight, but the English created the Famine.'

For this, John Mitchel was first charged with sedition. When that looked set to fail, the prosecution hurriedly changed it to Treason Felony. Mitchel was found guilty by an English jury and deported to Australia.

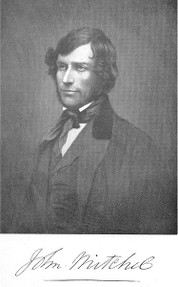

However, it wasn't only the Irish who were levelling charges of genocide at the English government. Its own prime minister, Robert Peel, felt the same way. He was forced to resign, when he was out-voted and out-manoeuvred on the Repeal of the Corn Laws.

Entering the legislate on June 26th 1846, these measures allowed 'money crops' to be taken out of Ireland without incurring any taxation at all.

Peel's closing speech railed against his profiteering peers, as he demanded, "Good God, are you to sit in cabinet and consider and calculate how much diarrhoea, and bloody flux, and dysentery a people can bear before it becomes necessary for you to provide them with food?"

His successor, Lord John Russell, openly reassured the business community that his government would no longer interfere with the grain market. By the following winter, prices on maize alone had 'virtually tripled'.

It was not an issue which was only determined by hindsight. In March 1847, the leader of the Conservative Party, Lord George Bentinck, was moved to question the ruling Whigs.

He spoke accusingly in Parliament, saying, "They know the people have been dying by their thousands and I dare them to inquire what has been the number of those who have died through their mismanagement, by their principles of free trade. Yes, free trade in the lives of the Irish people!"

During the same month, Queen Victoria herself was leading a Day of Atonement. The idea was for Christian people to have a day of fasting, as penance for the situation in Ireland. With such a patron, English congregations flocked to join her, but not to petition their government to do anything about it.

No doubt those Irish who heard about the gesture found it to be very cold comfort. But it is extremely telling that even the monarch judged that they had something about which to feel penitent.

Occasionally, a prominent member of parliament let slip their real motivation. Writing to an Irish landowner, the Chancellor of the Exchequer Sir Charles Wood actually stated, "I am not at all appalled by your tenantry going. That seems to be a necessary part of the process... We must not complain of what we really want to obtain."

Those representing the interests of the British government, actually inside Ireland, sometimes found the 'process' too much to bear. Edward Twisleton, an officer of the Poor Law Commission, resigned in 1849. He claimed that he was an 'unfit agent for a policy that must be one of extermination'.

His words were echoed a few months later, when Lord Claredon, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, wrote to his prime minister. He did not mince his words, raging, "I don't think there is another legislature in Europe that would disregard such suffering as now exists in the west of Ireland, or coldly persist in a policy of extermination."

His appeal for aid, like so many others before him, was solidly ignored.

Over half of the British army was stationed in Ireland during the potato blight.

Over half of the British army was stationed in Ireland during the potato blight.

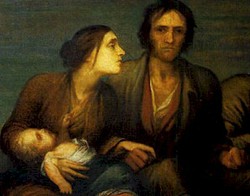

At the time of the potato crop failure, Ireland was ruled by Westminster. It was a British government which took the decisions that would prove so fatal to the Irish population.

At the time of the potato crop failure, Ireland was ruled by Westminster. It was a British government which took the decisions that would prove so fatal to the Irish population.

In 1861, Young Irelander John Mitchel wrote a pamphlet. In it, he stated that, 'Ireland was actually producing sufficient food, wool and flax, to feed and clothe not nine but eighteen millions of people'.

In 1861, Young Irelander John Mitchel wrote a pamphlet. In it, he stated that, 'Ireland was actually producing sufficient food, wool and flax, to feed and clothe not nine but eighteen millions of people'.

No-one has tried to argue that the British government acted well during the Irish famine, but was it

No-one has tried to argue that the British government acted well during the Irish famine, but was it  Kate

on 09/06/2012

Kate

on 09/06/2012

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Comments

Then please tell us what you learned from your Grandad. I can cover all the stuff that can be found in books. That's not particularly useful, because others can read the same books and discover the same information. What your Grandad told you and what you see around you every day, that is what's needful. New information to be shared.

Tell us about things like this: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CBE0t...

And if you ever need the history facts and figures, you shoot a private message over to me and I'll provide it for you to include in your articles.

Oh Jo!! I'm honoured and humbled that you think I may be capable of writing something worth reading. :)

It is a terrible shame that you never spoke with my Grandad before he died, you two would have had a lot to talk about, now there was a man who could have written an encyclopaedia, never mind an article!

I would have to do a LOT more study to be anywhere near ready to write articles. What I know I learned from speaking with my Grandad and from reading the books he owned. To write articles I feel that I would need to either be or have studied history full time as to make a mistake while purporting to know what I'm talking about would be unforgivable!!

I can shed some light upon the evolution of the names for our islands. I wrote this one: http://wizzley.com/difference-between... for foreign visitors here.

Michael, I would love for you to join Wizzley and write articles here on the issues under discussion. I've been planning plenty for Ireland myself - particularly with the Easter Rising century coming up in a couple of years time - but I've been focusing on Scotland and Wales just recently instead. It would be great to have a real mix going on.

As for history, it's never over. Three days ago, I was looking at the Tamar River and there were tears in my eyes, as I recalled battles that happened there over 1000 years ago. The Cornish NEVER gave up, yet they've been side-lined to the point where so many believe Kernow is part of England. It's not and it never was. It's not an armed occupation there, but one of economic sanctions, blockades and neglect. They're being dismissed into compliance.

Then there's Scotland. To me, it's such a no brainer which way people should be voting up there. Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes! For all those who would vote no, and keep Scotland in the Union, then I want to ram history books down their throats until they choke on the knowledge and precedents that they are ignoring. It's said that the definition of madness is to do something over and over again, with the same result, yet expect the next iteration to be different. With all due regard to the history books, it would be utter madness to vote no.

And for all those who say, 'but that's only history, it means nothing now; we've all grown up and we're all soooo much more fluffy and lovely than in the past, I say LOOK AT CORNWALL!' Every law passed in Westminster RIGHT NOW is illegally pressed onto the Cornish. When their Stannary is allowed to sit again, then perhaps Westminster might have given up on the Empire.

I should stop, because I'm full of cold/flu/virus/whatever it is, and exhausted too. I could rant forever. I'm Cymry and we have long, long, long memories. But Eire gave us heart. Thank you for that.

"the term, British Isles, is rooted in history."

And there it should remain. It was an inaccuracy to begin with when coined by whomever initiated the moniker........(someone british I'd wager) and then became indoctrinated into acceptance as the norm by educational sectors. But because it has been written, does not make it so.

"I spent a year,1969-1970, living in County Cavan on the border; and on one hike I nearly ran into the B specials [in Fermanagh]. Is any more comment needed? I was afraid, but escaped with my life. I have been followed down the Falls Road by soldiers, who spend the whole journey looking down machine guns at me, and I did not feel comfortable or safe. So I have lived with the Northern Irish problem, and I have felt fear."

A year is a year and I am glad that you experienced the truth of living here, however it is not lifetime and certainly not a drop in the ocean in the history of this land.

Again, I agree with some of your opinions outlined below but as this conversation has served to reveal, there are still deep wounds living inside the hearts and minds of the people here and abroad. Unfortunately, I do not see them being resolved any time soon. Certainly not without full acknowledgement, admission of guilt, sincere apologies, full military withdrawal and a guarantee of no further involvement in the affairs of this sovereign nation.

I feel that this discussion could go on indefinitely (especially if history is anything to go by), I also feel that I have made my position clear and I appreciate and understand your sentiments and point of view so I thank you for your time and thoughts and will exit now.

I spent a year,1969-1970, living in County Cavan on the border; and on one hike I nearly ran into the B specials [in Fermanagh]. Is any more comment needed? I was afraid, but escaped with my life. I have been followed down the Falls Road by soldiers, who spend the whole journey looking down machine guns at me, and I did not feel comfortable or safe. So I have lived with the Northern Irish problem, and I have felt fear.

Delineating a rational possibility does not mean that you support it. There are several rational possibilities, but the present situation is not one. My preferred option is a united Ireland that has strong friendship with a united Britain. Breach of friendship between the two islands would rip my family and friendships apart. Only tonight I spent the evening with my best friend, who is a Mayo man, and my wife is of a Mayo family, her maiden name was O'Rourke. I do not want to create splits or dissension.

The term British Isles is difficult, as I do not want to establish any British power over Ireland, but the term, British Isles, is rooted in history. The whole archipelago was known in ancient times as Prydain, of which there was Albion and Eire as the main islands, besides Mona, Mann. Vectis. Ebridae and Orcades. The Isles are geographically connected,and this should be the basis of co-operation between them. We need to move forward,as the legacy of past hatred only means pain

Frank, I'll have to disagree with you on those points. I don't think any of those options are feasible.

Firstly, nobody in Ireland accepts the moniker of "british isles". That is a title forced upon this country by centuries of occupation by a foreign power determined to delete the independent identity of this nation. I wholeheartedly reject any notion of this country being referred to in any way by the term british.

Secondly, even Scotland at present does not wish to be part of the current UK and they share an island with that nation. We have no connection whatsoever besides the military occupation of the North of Ireland.

The time for domination of, and identification by, what was the British empire has come to an end. Any nation is entitled to its identification by its own wish and definitions or the path will never be cleared for peaceful coexistence.

Unless you have lived here and seen armed soldiers belonging to a foreign power on your home soil then you honestly can not fully understand the situation.

To give you some perspective on this; think how you would feel if Germany had won WW2 and there were armed soldiers in German uniform walking the streets of the UK, stopping you from going about your daily business, searching and arresting you. WW2 was only 70 years ago. We've been putting up with that for centuries.

I believe that rational politics should adopt the principle that political entities should correspond to geographical, cultural and ethnic boundaries. There are two rational options in the British Isles:

1: A united, independent Britain next to a united, independent Ireland;

2: A united British Isles [with devolution to geographical and culural divisions]

[Choose which of the two suits you or what you think is best.]

Option 3 is not rationally justifiable: the present situation, in which Britain is united with a bit of Ireland.

Michael - We are definitely of the same opinion here. I'm very, very well aware of Irish History. Where possible, I undertook Irish history modules during my MA, and I've got bookshelves worth of history books about the country. I've written several articles on Wizzley about it too, so I'm trying to get the word out. :)

I too would love to see Eire united. I really, really would.

Frank and Michael - My apologies, gentlemen. I should have mentioned that I was heading off into the wilds of Somerset and Kernow for a couple of weeks. Hence I wasn't here to reply. I'm back now though!

Frank - It's good to see that you have some of the Gailege left too!

Those contemporary politicians showed no remorse, because they didn't seem to think it wrong what they were doing. It was 'only' the troublesome Irish dying in droves.

Hi again Frank, I am of the same opinion. I have no issue with the british public. I have many acquaintances in the UK from doing business there and have always found my encounters with the people of britain to be very pleasant in all aspects. I would like to see a time where apologies have been made and friendships forged from that, your Queen Elizabeth came almost as close as Mr. Blair did on her visit here and to hear her speak in Irish was a very unexpected but welcome part of her visit.

I also have many members of my family who are not nearly as interested in the history of the country so I understand where your brothers are coming from. History is just history to some of us where others of us find it more interesting and revealing.

I hope as our nearest neighbour and also our main trading partners, the future holds much brighter times than the past.

Slán go fóil mo chara. (Goodbye for now my friend) if you didn't already know!!