de la Rosa C.L.; Nocke C.C.. (2000). A Guide to the Carnivores of Central America: Natural History, Ecology, and Conservation. University of Texas Press.

d'Orbigny, Charles. Dictionnaire Universel d'Histoire Naturelle. Atlas de la Deuxième Édition. Zoologie: Races Humaines, Mammifères et Oiseaux. Tome Premier. Paris: Abel Pilon et Cie, n.d. (1867).

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at:http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/25404602

Eisenburg J.F. (1989). Mammals of the Neotropics. Volume 1: The Northern Neotropics. University of Chicago Press.

Eisenberg J.F.; Redford, K.H. (2000). Mammals of the Neotropics. Volume 3: The Central Neotropics. University of Chicago Press.

Ford L.S.; Hoffmann R.S. (27 December 1988). "Potos flavus." Mammalian Species 321:1-9. Retrieved on January 14, 2014.

Glatston A.R. (1994). "The Red Panda, Olingos, Coatis, Raccoons, and Their Relatives: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan for Procyonids and Ailurids." International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

Grzimek B. (2003). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Volumes 12-16: Mammals I-IV, second edition. Gale Cengage Learning.

Kays R.W. (May 1999). "Food preferences of kinkajous (Potos flavus): a frugivorous carnivore." Journal of Mammalogy 80(2):589-599.

Kays R.; Reid F.; Schipper J.; Helgen K. (2008). "Potos flavus." In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. Retrieved on January 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/41679/0

"Kinkajou." Honolulu Zoo. Internet Archive Wayback Machine. Retrieved on January 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://web.archive.org/web/20120402080432/http://www.honoluluzoo.org/kinkajou.htm

"Kinkajou (Potos flavus) #58-365." Comparative Mammalian Brain Collections. Retrieved on January 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://brainmuseum.org/Specimens/carnivora/kinkajou/index.html

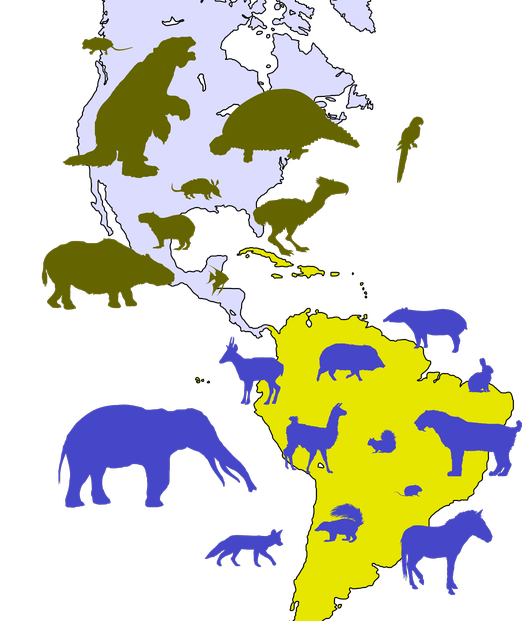

Koepfli K.-P.; Gompper M.E.; Eizirik E.; Ho C.-C.; Linden L.; Maldonado J.E.; Wayne R.K. (2007). "Phylogeny of the Procyonidae (Mammalia: Carvnivora): Molecules, morphology and the Great American Interchange." Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 43(3):1076-1095. Retrieved on January 14, 2014.

"Mammals: Kinkajou." San Diego Zoo Animals. Retrieved on January 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://animals.sandiegozoo.org/animals/kinkajou

McLeod L. "Kinkajous as Pets." About.com Pets: Exotic Pets. Retrieved on January 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://exoticpets.about.com/cs/rarespecies/p/kinkajou.htm

Menino H.; Klum M. "The Kinkajou." National Geographic Society. Retrieved on January 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/ngm/0310/feature2/index.html

Motta M.C.; Leiva M. "Jupará." Fundação Parque Zoológico de São Paulo. Retrieved on January 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.zoologico.sp.gov.br/mamiferos/jupara.htm

Murie. O.J. (1984). A Field Guide to Animal Tracks, second edition. Houghton Mifflin Company Peterson Field Guide Series.

Nowak R.M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World. Johns Hopkins University Press.

"Potos flavus." Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved on January 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://eol.org/pages/328067/details

"Potos flavus (Schreber, 1774)." ITIS Standard Report Page. Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved on January 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=621964

"Potos flavus Schreber 1774 (kinkajou)." Fossilworks Paleobiology Database. Retrieved on January 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://fossilworks.org/bridge.pl?a=taxonInfo&taxon_no=232928

Rehder D. (2007). "Potos flavus." Animal Diversity Web (On-line). University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved on January 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Potos_flavus/

"Wild Life Live! Kinkajou." Discover Oregon Zoo Exhibits. Retrieved on January 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.oregonzoo.org/discover/animals/kinkajou

Wozencraft W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora: Species Potos flavus." In: Wilson D.E.; Reeder D.M. (Eds.). Mammal Species of the World: a taxonomic and geographic reference, third edition. Johns Hopkins University Press. Retrieved on January 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.departments.bucknell.edu/biology/resources/msw3/browse.asp

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Comments

Tolovaj, Kinkajous are unknown to many, even though they are very pleasing as exotic pets. I'm glad that you enjoyed the photos.

I never heard about them. Lovely photos!

Jo, Yes, they are adorable!

They are so ridiculously cute!