Adolt, Radim; Pavlis, Jindrich. (2004). “Age structure and growth of Dracaena cinnabari populations on Socotra”. Trees – Structure and Function, 18 (2004): 43-53.

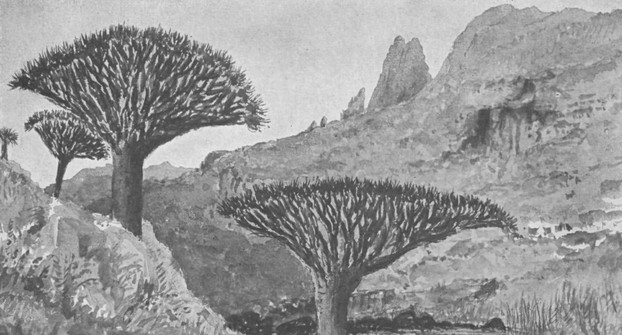

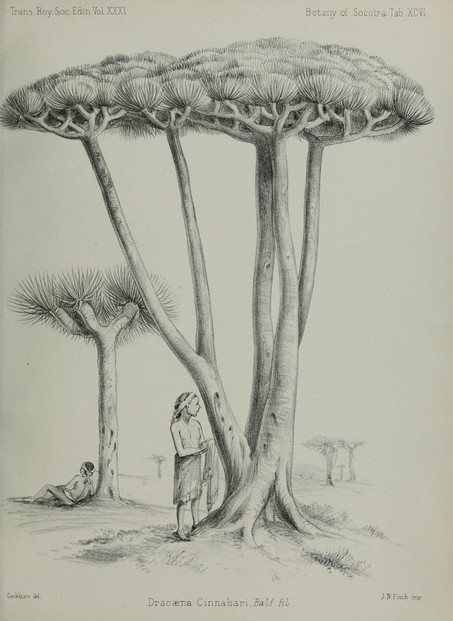

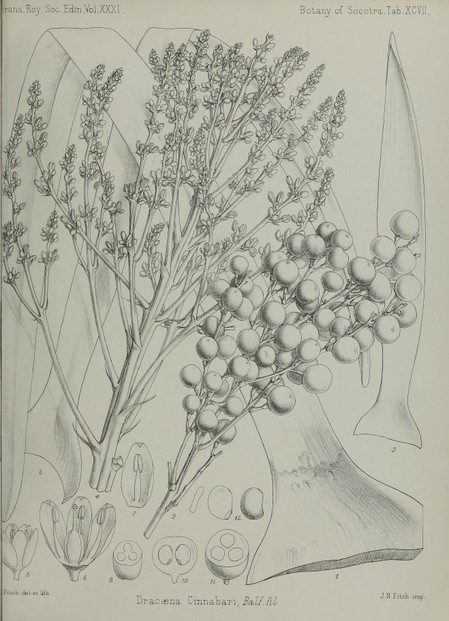

Balfour, Isaac Bayley. “Botany of Socotra.” Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences. Volume XXXI (31). Edinburgh: Robert Grant & Son; London: Williams & Norgate, MDCCCLXXXVIII (1888).

- Available at Google Books at: http://books.google.com/books/about/Transactions_of_the_Royal_Society_of_Edi.htmlid=dB5XAAAAYAAJ

Balfour, Isaac Bayley. Botany of Socotra. Forming Vol. XXXI of The Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Edinburgh: Robert Grant & Son; London: Williams & Norgate, MDCCCLXXXVIII (1888).

- Available at Biodiversity Heritage Library at: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/42457

- Available at Internet Archive at: http://archive.org/details/botanyofsocotra00balf

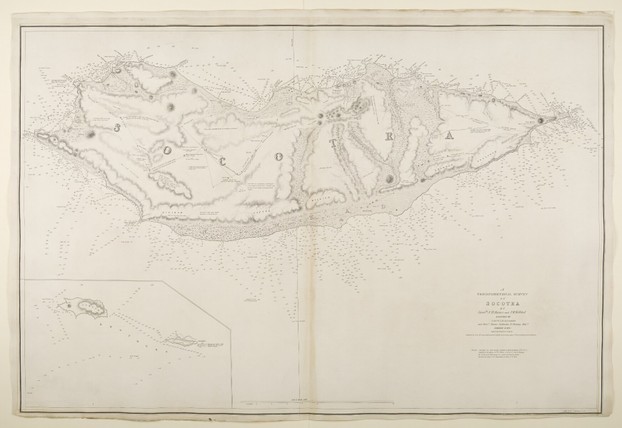

Bent, Theodore, and Mrs. Theodore Bent. Southern Arabia Soudan and Socotra. With a Portrait, Maps, and Illustrations. London: Smith Elder & Co., 1900.

- Available via Google Books at: http://books.google.com/books/about/Southern_Arabia.htmlid=jNoTAAAAIAAJ.

- Available via Project Gutenberg at: www.gutenberg.org/files/21569/21569-h/21569-h.htm

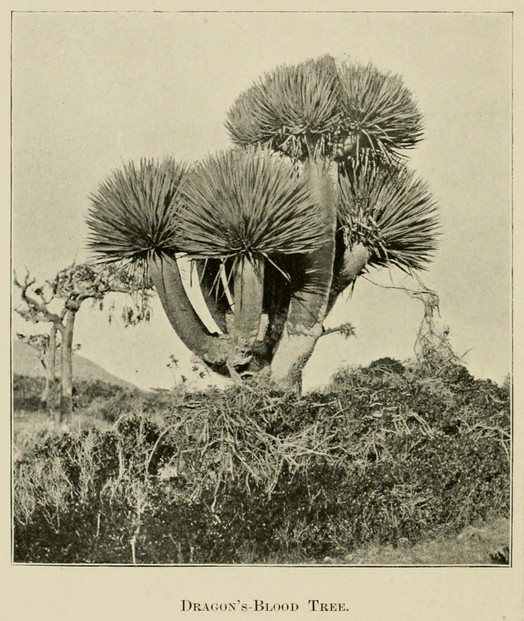

Botting, Douglas. Island of the Dragon's Blood. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1958.

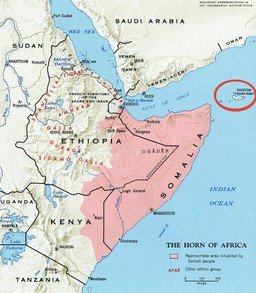

Boxhall, P.G. "Socotra: 'Island of Bliss.'" The Geographical Journal, Volume 132, Number 2 (June, 1966): 213-222.

Baumer, Ursula, and Patrick Dietemann. (2010). "Identification and differentiation of dragon's blood in works of art using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry." Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 397 (2010):1363-1376.

Cheung, Catherine, and Lyndon DeVantier. Socotra: A Natural History of the Islands and their People. Hong Kong: Odyssey Books & Guides, 2006.

“Decisions Adopted at the 32nd Session of the World Heritage Committee (Quebec City, 2008)." United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage World Heritage Committee Thirty-second session Quebec City, Canada 2-10 July 2008. World Heritage 32 COM. WHC-08/32.COM/24 Rev 31 March 2009. Paris, France: UNESCO World Heritage Centre, May 2009.

- Available at: http://whc.unesco.org/archive/2008/whc08-32com-24reve.pdf

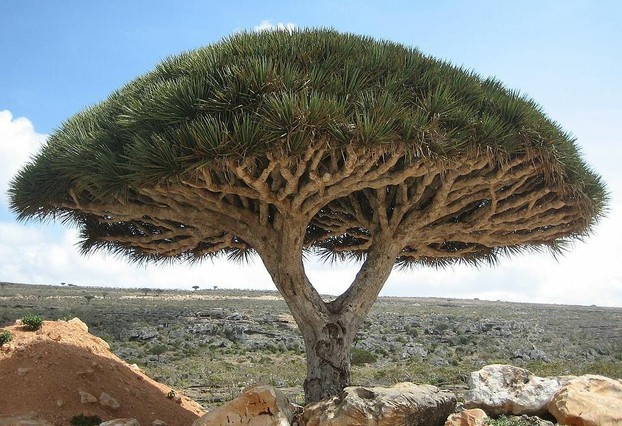

“Dragon’s blood tree (Dracaena cinnabari)". ARKive Images of Life on Earth: Plants and algae. 2003-2011.

- Available at: http://www.arkive.org/dragons-blood-tree/dracaenacinnabari/image-G70994.html

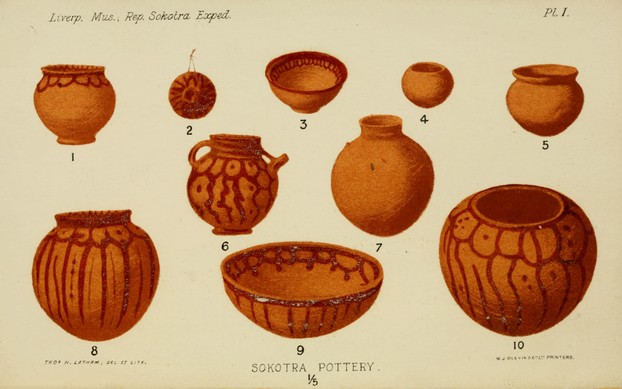

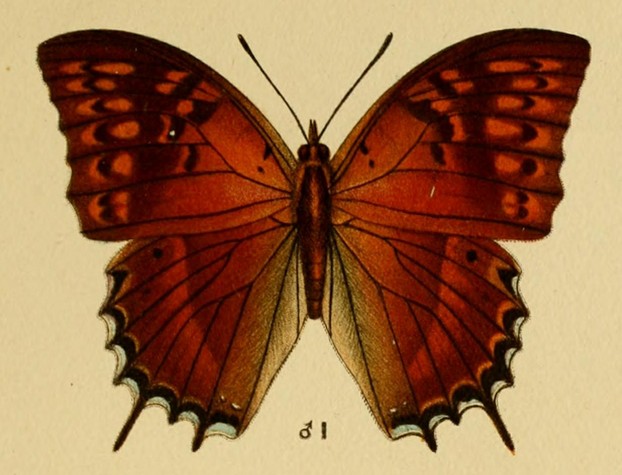

Forbes, Henry O., ed. The Natural History of Sokotra and Abd-el-Kuri: Being the Report upon the Results of the Conjoint Expedition to these Islands in 1898-9, by Mr. W.R. Ogilvie-Grant, of the British Museum, and Dr. H.O. Forbes, of the Liverpool Museums, together with information from other available sources Forming A Monograph of the Islands. Liverpool-London: The Free Public Museums, 1903.

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/80063

- Available via Internet Archive at: http://archive.org/details/naturalhistoryof00forb

Gupta, Deepika; Bleakley, Bruce; Gupta, Rajinder K. “Dragon’s blood: botany, chemistry and therapeutic uses.” Journal of Ethnopharmacology, Vol. 115, No. 3 (2008): 361-380.

Miller, Anthony G. (2004). "Dracaena cinnabari". In: IUCN 2011. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.1.

- Available at: http://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/30428/0

Petroncini, Serena. "Survey and monitoring of Dracaena cinnabari Balf.Fil. in Soqotra Island (Yemen)". In: ETFRN [European Tropical Forest Research Network] News 36: New Instruments for Monitoring and Evaluation: Organisations – Programmes.

- Available at: http://www.etfrn.org/ETFRN/newsletter/news36/n136_oip7.html

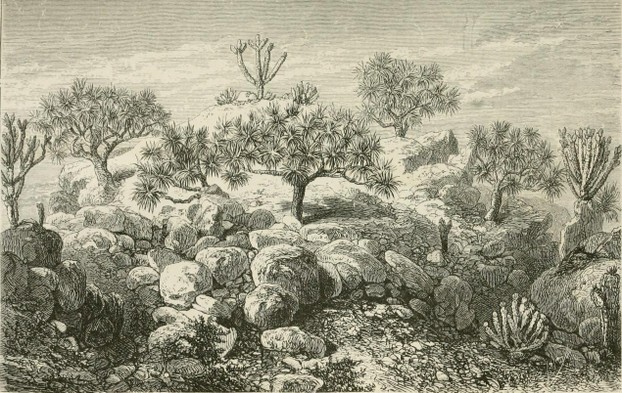

Schweinfurth, Georg. The Heart of Africa. Three Years' Travels and Adventures in the Unexplored Regions of Central Africa from to 1871. Translated by Ellen E. Frewer. With an Introduction by Windwood Reade. In Two Volumes. Vol. I. With Maps and Woodcut Illustrations. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Low, and Searle, 1874.

- Available via Internet Archive at: http://archive.org/details/heartofafricathr01schw

Sclater, P.L. (Philip Lutley), and Dr. G. Hartlaub. "On the Birds Collected in Socotra by Prof. I.B. Balfour." Proceedings of the Scientific Meetings of the Zoological Society of London for the Year 1881, January 4, 1881: 165-175. London: Messrs. Longmans, Green, Reader and Dyer, 1881.

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/96698

Silverstein, Shel. The Giving Tree. New York: Harper & Row, 1964.

Stang, David. (2009). Dracaena cinnabari (Dragon’s Blood Tree). ZipcodeZoo.com, 2004-2011.

- Available at: http://zipcodezoo.com/Plants/D/Dracaena_cinnabari/

“Socotra Archipelago.” United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization World Heritage Convention: The List. UNESCO World Heritage Centre, 1992-2011.

- Available at: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1263

Wellsted, J.R. "Memoir on the Island of Socotra." Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, Vol. 5 (1835): 129-229.

- Available via Internet Archive @ https://archive.org/details/s572id13663570/page/129/mode/1up

Wellsted, James Raymond. Travels to the City of the Caliphs along the Shores of the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean: Including a Voyage to the Coast of Arabia, and a Tour on the Island of Socotra. In Two Volumes. Volume II. London: Henry Colburn, 1840.

- Available via Google Books at: books.google.com/books?id=S-YDAAAAQAAJ

- Available via HathiTrust at: http://hdl.handle.net/2027/nnc1.0035548509

- Available via Internet Archive at: http://archive.org/details/travelstocityca02wellgoog

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Date12 days ago

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Date12 days ago

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 202413 days ago

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 202413 days ago

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2023on 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2023on 04/13/2023

Comments

VioletRose, Me, too: plants and trees present such fascinating variety that they always hold my interest.

Very interesting, I love learning about plants and trees.