© by Terry McNamee

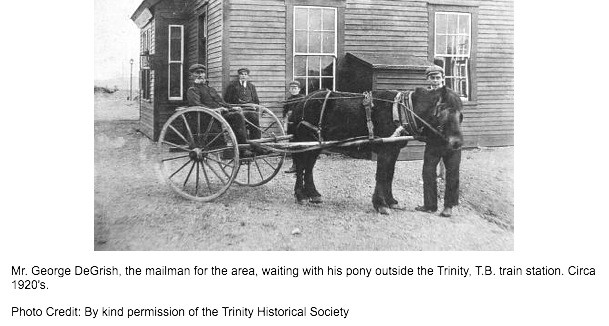

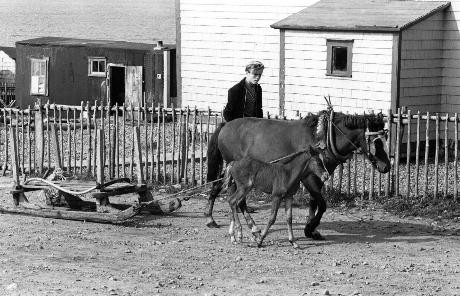

Life on the island of Newfoundland was, and in some cases still is, based on subsistence farming and fishing. The first non-Native immigrants were the Vikings, who settled there briefly around AD 1000, but they were driven out by the native Beothuk people and they left no horses behind. A few European settlements began to emerge after 1600, but most residents were seasonal, living there only long enough to catch and dry cod to sell in Europe or to go whaling and sealing. Farming was not really part of the equation until the late 1700s, but those who did farm arrived in Newfoundland with ponies, sheep and cattle. After Newfoundland was recognized as a British colony in 1824, more immigrants started arriving from the British Isles (primarily from Ireland and Scotland). They brought Galloways and Highland Ponies from Scotland, a few Connemaras from Ireland, some Dartmoor, Exmoor, Fell and New Forest Ponies from England, and all four types of Welsh Ponies and Cobs from Wales. Today, the Galloway, a large pony or small horse 12 to 14 hands and similar to the Welsh Cob, is extinct due to crossbreeding with draft horses in its native Scotland, but its genes live on in the Newfoundland Pony and Scotland's rare Eriskay Pony.

Versatile Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retrieverson 08/02/2014

Versatile Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retrieverson 08/02/2014

Should You Spay or Neuter Your Puppy?on 08/12/2014

Should You Spay or Neuter Your Puppy?on 08/12/2014

Horse Racing History: the Preakness Stakeson 05/15/2014

Horse Racing History: the Preakness Stakeson 05/15/2014

Dinosaurs Will Be On Display in Trenton, Ontario, Canadaon 07/29/2013

Dinosaurs Will Be On Display in Trenton, Ontario, Canadaon 07/29/2013

Comments

Interesting, my cousin love horses, it's her life, going to forward this to her.

Great article! Sad they are not yet recognized!