Varanus giganteus is native to Australia, where it commonly is known as perentie.

The common name is adopted from aboriginal languages of the northeastern part

of the State of South Australia in south central Australia. There Varanus giganteus

is known as pirrhinti by the Diyari tribe and as pirrinti by the Arabana tribe.

Dreamtime Perenties: Australia's Enormous Varanus Giganteus on the Prowl

The largest lizard in its native Australia, perentie (Varanus giganteus) has iconic associations with historic and prehistoric landscapes. This intrinsic connection is explored.

The genus Varanus comprises over fifty species with a prehistoric distribution evinced by varanid fossils on all continents except Antarctica and South America. In the New World, fossils of varanids are present in North America. The presence of a venomous sister group, Helodermatids (genus Heloderma), occurs natively in Central and North America, stretching from the southwestern United States south to Guatemala. A well-known member of this relative is the Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum), which is native to the southwestern United States and the northwestern Mexican state of Sonora and which has protected status in Arizona and Nevada.

Varanids are presently found throughout Africa, Asia, and Australia. In fact, twenty-four species of Varanus have been identified as endemic (Greek: ἐν, en, “in” + δῆμος, demos, “people, district”) to Australia because their specific geographic range is found only there, which "to a very large extent . . . is a land of lizards," particularly in the Red Sands of Western Australia's Great Victoria Desert with its unequalled reptilian diversity (Hedley Herbert Finlayson, The Red Centre). Fossil evidence places the existence of varanids as far back as 90 million years ago.

The oldest known Varanus fossil in Australia dates about 23 million years ago to the Early Miocene

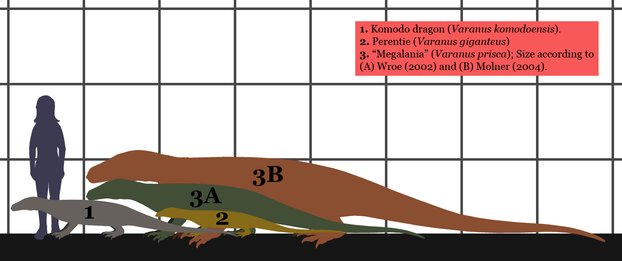

Period (Greek: μείων, meiōn, “less” + καινός, kainos, “new”). One of perenties' relatives, Megalania prisca ("Ancient Great Roamer"), also known as Varanus prisca, inhabited eastern Australia, roaming from the southern coast near Melbourne in the southeastern state of Victoria all the way up north to Queensland's Cape York Peninsula. An absence of complete skeletons precludes precision in size. Total length is estimated variously between 20 to 32 feet (6 to 10 meters), with a weight of over 1,322 pounds (600 kilograms). Known commonly as giant ripper lizard, Megalania left fossil reminders of its existence before its probable extinction about 30,000 to 40,000 years ago in the late Pleistocene (Greek: πλεῖστος, pleistos, "most" + καινός, kainos, "new") Epoch. It is entirely possible that Australia's first human inhabitants encountered Megalania in their respective roamings.

The point of origin for the varanid diaspora has not been conclusively determined. Speculation focuses on Africa, Asia, and possibly, though seemingly unlikely, Australia.

Australians refer to varanids of all sizes as "goanna," which is thought to be a corruption of iguana, which actually is a lizard native to Central and South America and the Caribbean.

Distribution ~ Habitat ~ Shelter

Distribution

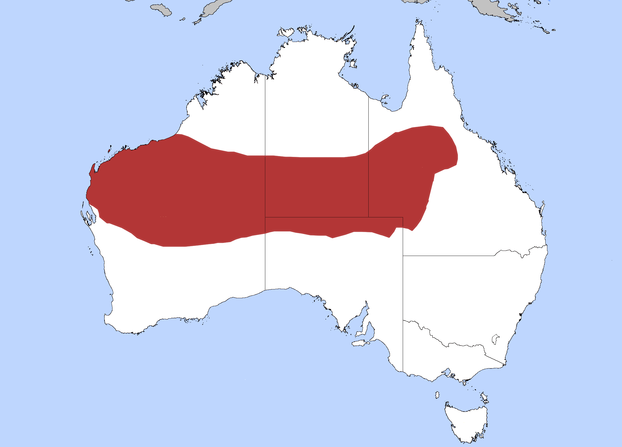

Perenties' distribution ranges throughout arid regions banding from northwestern New South Wales to the west coast. Perenties favor Northern Territory, Queensland, South Australia, and Western Australia as well as many islands off the west coast, especially on Barrow Island.

Habitat

Perenties prefer desert regions intersected by rocky terrain with deep crevices or caves for burrowing. Nevertheless, they also inhabit grasslands and shrublands without rocky outcrops as well as sandy flatlands. Although perenties are terrestrial (Latin: terrestris, "earthly" [from terra, "earth"]) lizards, they have been observed avoiding human interaction by taking refuge in nearby trees in the absence of any other viable escape route!

Shelter

Perenties prefer to seek shelter in caves and crevices. In the absence of exposed rock, they use their powerful front legs and claws to dig burrows or to appropriate existent tunnels. For instance, on Barrow Island in Western Australia, perenties preempt underground homes dug by boodies, or burrowing bettongs (Bettongia lesueur), a small marsupial relative of kangaroos averaging about 15 inches (40 centimeters) in length.

Perentie size

As the largest lizard in Australia, Varanus giganteus is characterized by length at both ends: a long neck sleekly flows into a robust body, which ends in a long, tapering tail. Varanus giganteus adult males have an average total length, from the tip of the nose to the tip of the tail, of around 5.2 feet (1.6 meters). Nevertheless, maximum total lengths have been recorded that range from 6.5 to 8.2 feet (2 to 2.5 meters). Females usually have shorter lengths than males. The total length of captive-born perentie hatchlings averages about 1.2 feet (0.37 meters).

The tail usually accounts for one-and-one-fifth (1.20) to one-and-one-half (1.5) of the snout-to-vent length (SVL), a standard measurement of body length in lizards that is demarcated at one end by the snout (tip of the nose) and at the other end by the cloaca (Latin: cloaca, "sewer, drain [from cluere, "to cleanse"]) or vent, which is the posterior vent that is the opening for the digestive, reproductive, and urinary tracts.

An average weight of almost 10 pounds (4.46 kilograms) has been reported from a range of 0.33 to 25.7 pounds (0.15 to 11.7 kilograms). Maximum adult weights in excess of 38 pounds (17.24 kilograms) have been recorded. The weight of captive-born perentie hatchlings averages about 0.09 pounds (40 grams).

Coloring

Adult dorsal (Latin: dorsalis, "of or relating to the back") coloring, that is, on the upper side or back, is a stippled pattern of rows of cream or yellow spots with dark brown to black centers and edges. Undersides are whitish.

Diet

In their food forages, perenties are willing to wander at length over open plains and on the sparsely arbored expanses of Australia's gibber (rocky rubble or fragments) plains with their loose, variable-sized rocks and stones. Perenties have keen senses that enable them to be superb trackers. As they flick their highly sensitive forked tongues in and out of their mouths, they are extracting, from the air and the landscape, chemicals, which are translated, as the tongue withdraws briefly into its sheath, into meaningful information for its brain by Jacobson's organ, a olfactory sense organ contained within two pits on the roof of its mouth. Moreover, their tracking abilities extend below ground as well. Thus, perentie prey have great difficulty in eluding this predator.

Perenties, especially juveniles, are known to devour centipedes (class Chilopoda anthropods), grasshoppers (suborder Caelifera insects), and spiders (order Araneae arthropods). Nevertheless, the typical adult perentie diet is almost exclusively carnivorous. Dietary staples include birds, eggs (especially turtle), and small marsupials (i.e., wallabies [family Macropodidae]). Perenties have also added to their diet the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus), which were first introduced into Australia in 1859 by pioneer settler Thomas Austin at his 29,000 acre (12,000 hectare) estate, Barwon Park, in Winchelsea in the state of Victoria.

Although perenties have acquired a taste for European rabbits, populations of this mammal only need to fear their other predator, European red fox (Vulpes vulpes) in Tasmania, which is too cool for sun-basking perenties.

European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) in Austin's Ferry, new home suburb of Hobart, southeastern Tasmania |

Size of prey does not intimidate perenties. Basically, any creature that Varanus giganteus can overpower serves as prey. They also feed on carrion, including road-killed kangaroos. Generally, perenties swallow their victims whole. If their prey is too large to be swallowed whole, perenties use their powerful front legs and claws to dismember them into consumable pieces. In this manner they have been observed consuming large kangaroos (family Macropodidae).

Perenties also devour snakes (suborder Serpentes). Herpetologist Gavin Bedford of Darwin in Australia's Northern Territory reported that he radiotracked a central carpet python (Morelia bredli), a non-venomous Australian native typically over 6.5 feet (2 meters) in length, to an old rabbit burrow near the Alice Springs airport, which revealed, when dug open, a male perentie of 5.9 feet (1.8 meters). The perentie disgorged a large, mulga snake (Pseudechis australis), which is the second longest snake in Australia, with a length ranging from 8.2 to 9.8 feet (2.5 to 3 meters). Dr. Bedford cut the venomous snake's carcass open to find the dead carpet python inside.

Mealtime: Perenties walking around with tails hanging out of their mouths

Lizards, however, are a major food source. Perenties favor large and dwarf goannas and exhibit cannibalism by devouring weaker members of their own species. Documented cannibalism include the observation of a 4.9 foot (1.5 meters) perentie swallowing most of a 3.9 feet (1.2 meters) perentie and then walking around with all 1.5 feet (0.5 meters) of the victim's tail hanging out of its mouth. In another instance, a juvenile perentie, about 2 feet (0.6 meters) in length, ingested the body of an agamid lizard of nearly its same length, a long-nosed water dragon (Lophognathus longirostris), about 1.6 feet (0.5 meters) long, and the juvenile was seen with the majority of the victim's tail trailing out of its mouth for the next 24 hours.

Echidnas: Prickly fatal attraction as perentie prey

Covered like porcupines with sharp spiny quills, spiny anteaters, also known commonly as echidnas (family Tachyglossidae), are one of the few mammals that generally does not cringe or cower at a perentie encounter. Any perentie that does succeed in swallowing an overpowered echidna in all likelihood lives just long enough to regret the food choice because the echidna's quills fatally perforate the perentie's innards in the course of being ingested. Such encounters are rare but have been documented postmortem.

The question remains whether the consumption was attempted on carrion or on live prey. Either way, fatality ensues regardless of the motivation, be it in desperation or in a rare flash of lack of intelligence.

A grisly mummified reminder of such an unfortunate encounter is housed in the Museum of Brisbane in sunny Queensland.

Predators sometimes make irreversible mistakes in prey: fatal encounter of short-beaked echidna in perentie's mouth, with a loss of life for both, but more gruesome for perentie ~ echidna's spines (upper left) in perentie's open mouth (upper right).

perentie vs short-beaked echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus) ~ Museum of Brisbane, southeast Queensland |

Breeding

About four weeks elapses between mating and deposition of about five to eleven eggs into a burrow, which occurs in late summer. With a long incubation period averaging at about 219 days (a little over seven months), the eggs overwinter and hatch in the next spring or summer.

Hibernation and thermoregulation

As an ectotherm (Greek: εκτός, ektós, "outside" + θερμός, thermós, "hot"), perenties regulate their body temperature by absorbing heat from the external environment. Their activity patterns reflect seasonal and environmental conditions, such as temperature. During the Australian winter in June, maximum activity occurs during warmest times of the day, whereas in summer (December to February) major activities coincide with cooler times of the day. Perenties hibernate during the coldest months, from May to August.

Because they do not generate their own sustained body heat, perenties have ongoing concerns with thermoregulation, whereby they often shuttle sensitively between sun and shade. When the earth's surface sizzles, perenties may sink into the cool depths of underground burrows or caves or even seek breezes or strong winds by climbing shrubs or trees. Basking is a familiar reptilian posture that is reminiscent of human sunbathing, only perenties are getting warm rather than tanned.

Maintaining the proper body temperature has also been known to trouble several female perenties at bedtime. One female scoured half a dozen crevices before settling in for the night. Another thought that she was retiring for the night but when her body temperature began rapidly decreasing, she evacuated the burrow and located a rocky crevice in which her temperature stabilized.

Tripoding: Surveying the world while basking

A typical posture is the triangular position favored by quadrupeds called tripoding in which a perentie settles back on its tail and haunches while its upper body is upraised and supported by the full length of its front legs. In this posture, perenties may crane their necks for an even better view of their surroundings. Remaining in this position, they also enjoy the sun's warmth. This favorite varanid posture accounts for the common name for this genus, monitor (Latin: monere, "to warn") lizards, in recognition of their predilection for regularly surveying and monitoring their domain.

"The Perentie," Sir David Attenborough's Life in Cold Blood BBC documentary (globalzoo, YouTube)

Ploys for disengaging unwelcome attention: From spacing out to intimidating to evading

Varanus giganteus resorts to various ploys for dissuading unwelcome or unexpected approachers. They display uninterested behavior by staring into space, acting as though they are unaware of the visitor's presence. Sometimes perenties crouch low to the ground, almost as though they are flattening themselves into the earth. Other times, if feeling provoked, they may choose to rise up pugnaciously on their hind legs, towering over the unwanted guest, and hissing. An anecdotal, though not common, reaction involves intentionally or unintentionally maiming through lashing out with its mighty tail. Thus, a dog's forelegs were alleged to have been broken, and a native woman was felled to the ground.

Or perenties may engage in the kinesthetic reaction of running away, an agile, graceful, and highly successful choice. Perenties are endurance runners as, unlike most lizards, they are able to run continuously and lengthily. Because the anatomy of most lizards requires them to use the same muscles both for inflating their lungs and for moving, they are not efficient or effective long-distance runners. On the contrary, Varanus lizards are endowed with large, muscular throats which function like bellows by pumping air into their lungs. In this way, typical of the Varanus genus, gular (Latin: gula, "throat") pumping does not interfere with running and in fact enhances perentie swiftness, enabling them to attain speeds of over 20 miles (32 kilometers) per hour.

Varanid swiftness is further sustained by raising their forelimbs from the ground to run bipedally on their back legs. Greg Fyfe, while a ranger at Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park, the UNESCO World Heritage natural and cultural site in the lower southwestern portion of the Northern Territory, was quickly outdistanced at Ayers Rock (Uluṟu) by a perentie that switched easily from quadrupedal to bipedal running. Moreover, the perentie did not swerve around obstacles such as fallen branches piled to a height of 3.3 to 6.6 feet (one to two meters). Rather, the perentie plunged directly at the pile,

". . . slid up and over it without slowing down. Maybe the raised and inclined body

enabled the perentie to 'ski jump' or toboggan over these obstacles . . ." (Pianka &

King, p. 344)

Dreamtime perentie: Ngintaka in Tjukurpa (The Dreaming)

Perenties have a special, sacred status in indigenous Australian mythology. They are connected with the journey of creation through Tjukurpa, the Dreaming. The Australian landscape abounds in unique features, such as Uluru (Ayers Rock), which are considered to be living vestiges created during the Dreaming as vital reminders of the mythological Spirit Being ancestors of Australia's first human inhabitants.

Tjukurpa ngaranyi pulingka munu iwara, ankuntja, tjukurpa ankuntja:

"This is a story of rocks and tracks"

The Pitjantjatjara, known to themselves as Aṉaŋu or Arnangu ("human being, person"), are indigenous to an area that radiates out from Uluru. One of their totemic Creation Beings is a perentie named Ngintaka, who, during a search for the perfect stone (tjiwa) for grinding wild pigweed (Portulaca oleracea) seeds for making seed cakes (kind of bush bread), created the landscape from his home in a place named Ataramula near the Western Australian border eastwards to Oodnadatta (Arrernte: utnadata, "mulga [Acacia aneura tree] blossom") in the upper mid-northern part of the state of South Australia.

This area created by Perentie Man (wati ngintaka) is known as Angatja, which, with its location in the Mann Range near the border with the state of Western Australian, is one of the northernmost localities in the state of South Australia. Driving distance to Angatja from Uluru (Ayers Rock) is about four hours. Situated around 2,300 feet (700 meters) above sea level, Angatja is also one of the higher localities in South Australia. Angatja is about 783 miles (1,260 kilometers) northwest of South Australia's coastal capital city, Adelaide.

The Mann Range is part of the Central Ranges, which also comprise Petermann and Musgrave Ranges. These mountains and hills wind through contiguous borders of the Northern Territory with the states of South Australia and Western Australia. This rugged area, surrounded by Quaternary (less than 10 million years ago) red alluvial sand plains, is the heartland of Pitjantjatjara Lands.

Mountains arose wherever Ngintaka rested. Salt lakes were created wherever his tail scraped the ground. Vegetation, especially kaltu-kaltu or native millet (Panicum decompositum), highly treasured for seed cakes, and food plants (mayi) and actual seeds (uninypa), as well as numerous perenties, streamed out of Ngintaka's mouth.

Ngintaka's landmarks and plants are sacred legacies which were entrusted through the Dreaming to indigenous Australians for caretaking and immortalizing in ritualistic appreciation of the wavering boundaries between Dreamtime and real time.

Forever perenties

From its prehistoric role in Australia's creation myths to its modern cachet as innovative, reliable, and versatile off-road vehicles of uniquely Australian design, Varanus giganteus has timeless associations with its native land. In its comfortable prowl through its uniquely Australian domain, Varanus giganteus links past with present and mythological time with so-called real time. Perhaps it is strong evidence of Varanus giganteus' inherent harmony with its ecosystem that this endearing, enduring species has been, and continues to be, inextricably intertwined with the sense of place that is evoked within Australians for their decidedly unique landscape.

"Built For The Kill - Island - Perentie" (Paleoworld101, YouTube)

Dedication

This article is dedicated to the memory of renowned Pintupi artist Clifford Possum Tjaplatjarri (1932-June 21, 2002) in appreciation of his exquisite artistic talents, especially in painting Dreamtime images.

Acknowledgment

My special thanks to talented artists and photographers/concerned organizations who make their fine images available on the internet.

Image Credits

Perentie in Perth Zoo, Western Australia: SeanMack, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Perentie_Lizard_Perth_Zoo_SMC_Spet_2005.jpg

Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum, Tucson: SearchNet Media, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Heloderma_suspectum_-Arizona-Sonora_Desert_Museum-8a.jpg

estimated sizes of extant monitor lizards comparative to size estimates for Megalania: Conty, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Extant_Monitor_lizards-Megalania_SIZE.png

skeletal reconstruction of Megalania, steps of Melbourne Museum, Carlton Gardens, south central Victoria: Casliber, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Varanus_priscus_Melbourne_Museum.jpg

distribution of perentie in land down under: Nrg800, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Perentie.png

perentie in Red Centre, southern Northern Territory, central Australia: Masteraah, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:Perentie.jpg

Closeup of perentie's head, in wild near 17-Mile Quobba Station, on coast about 100 miles from Canarvon, West Australia: Richahel, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Perentie_closeup.png

gibber plains in seemingly endless stretch across bordering states of Queensland and South Australia: Jussarian, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Flickr @ https://www.flickr.com/photos/90511472@N00/527230197/

European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) in Austin's Ferry, new home suburb of Hobart, southeastern Tasmania: JJ Harrison, CC BY SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Oryctolagus_cuniculus_Tasmania_2.jpg

perentie's sharp claws ~ Ayers Rock Resort, Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, Northern Territory, central Australia: F Delventhal (krossbow), CC BY 2.0, via Flickr @ https://www.flickr.com/photos/krossbow/462076489/

short-nosed echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus): should be removed by perenties from their prey list: bazzat2003, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tachyglossus_aculeatus_ss.jpg

perentie vs short-beaked echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus) ~ Museum of Brisbane, southeast Queensland: Orin Zebest, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Flickr @ https://www.flickr.com/photos/orinrobertjohn/148581560/

baby perentie, cautiously inquisitive ~ Wild Life Sydney, Darling Harbour, southeastern New South Wales: Aaron Gustafson, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Flickr @ https://www.flickr.com/photos/aarongustafson/1508044718/

Typical tripoding pose ~ in the wild near 17-Mile Quobba Station, on coast about 100 miles from Canarvon, West Australia: Richahel, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Pirentie_tripodding.JPG

partial tripod: most of body resting on ground, but still alert~in habitat, Coral Bay, northwestern Western Australia: Harclade, CC BY SA 2.0, via Flickr @ https://www.flickr.com/photos/harclade/4239610803/

globalzoo, "The Perentie," YouTube, Jan. 21, 2010, @ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=614hIg2lNM8

Unique Uluru, with spinifex grass (Triodia irritans) in foreground: nosha, CC BY SA 2.0, via Flickr @ https://www.flickr.com/photos/nosha/2836119312/

panorama of Kata Tjuta (Pitjantjajara: "many heads"): Christian Mehlführer (Chmehl), CC BY 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:MC_Olgas_pano.jpg

common purslane, also known as pigweed (Portulaca oleracea), capsules, closed, with one open to reveal seeds: Loasa, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Portulaca_oleracea_fruit01.jpg

Lake Amadeus: Württemberg (1822-1892) Source:http://www.flickr.com/photos/donmaedi/157324335/

*Removed, per URL message: 404 This is not the page you’re looking for. It appears the photo or video you seek no longer exists.

native millet (Panicum decompositum): Harry Rose (Macleay Grass Man), CC BY 2.0, via Flickr @ https://www.flickr.com/photos/73840284@N04/8243411144/

Paleoworld101, "Built For The Kill - Island - Perentie," YouTube, Dec. 16, 2009, @ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ykheaHXNN08

head and neck closeups of two perenties in Perth Zoo, Western Australia: Helenabella, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Perentie_Lizard_Pair.jpg

Perenties rest in sand near dead wood~Snakes Downunder Reptile Park, Childers, south Queensland, northeastern Australia: Michael Zimmer (zayzayem), CC BY-SA 2.0, via Flickr @ https://www.flickr.com/photos/zayzayem/5822981849/

perentie in Australian Outback: Avia55, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr @ https://www.flickr.com/photos/81715383@N00/4127569272/

Sources Consulted

Bennett, Daniel. A Little Book of Monitor Lizards. Viper Press, 1995.

Bosnak, Robert. Tracks in the Wilderness of Dreaming. New York: Delacorte Press, 1996.

DPIPWE Pest Risk Assessment: Perentie (Varanus giganteus). Hobart, Tasmania: Tasmanian Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment, December 2011.

- Available at: http://www.dpiw.tas.gov.au/inter.nsf/Attachments/JTIN-8R7VU2/$FILE/ Perentie_risk%20assessment_Final.pdf

Finlayson, Hedley Herbert. The Red Centre. London: Angus & Robertson, 1943.

Flood, Josephine. Archaeology of the Dreamtime. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1983.

Flood, Josephine. "Linkage between rock-art and landscape in Aboriginal Australia" (pp. 182-200). In: Christopher Chippindale and George Nash, eds., The Figured Landscapes of Rock-Art: Looking at Pictures in Place. Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Jauncey, Dorothy. Bardi Grubs and Frog Cakes: South Australian Words. Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2004.

King, Dennis, and Brian Green. Goannas: The Biology of Varanid Lizards. 2nd ed. Australian Natural History Series. Sydney: University of New South Wales, 1999.

Kirschner, Andreas, Thomas Müller, and Hermann Seufert. Faszination Warane: Pflege und Zucht. Rheinstetten: Kirschner & Seufer Verlag, 1996.

Naish, Darren. "Perentie tries to swallow echidna. Echidna too spiky. Perentie gets horribly injured. Dies." ScienceBlogs: Tetrapod Zoology. December 4, 2009. (Last accessed October 7, 2013)

- Available at: http://scienceblogs.com/tetrapodzoology/2009/12/04/perentie-dies-swallowing-echidna/

Pianka, Eric R. Ecology and natural history of desert lizards: analyses of the ecological niche and community structure. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1986.

Pianka, Eric R. The Lizard Man Speaks. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1994.

Pianka, Eric R., and Dennis R. King with Ruth Allen King, eds. Varanoid Lizards of the World. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004.

Reed, Alexander Wycliff. Aboriginal Fables and Legendary Tales. Wellington: Reed Books Australia, 1994.

Somerville, Margaret. Body Landscape Journals. North Melbourne: Spinifex Press, 1999.

Reptiles and Amphibians of Australia by Harold G. Cogger

This classic work, originally published in 1975, has been completely brought up to date. This seventh edition includes all species described prior to October 2013.

|

| perentie-themed books |

You might also like

Australia's Flaming Red Spires: Gymea Lily (Doryanthes excelsa)Native only in the area of Sydney, wild Gymea lilies reach heights of 16 feet...

Ring-Tailed Rock Wallaby (Petrogale xanthopus) of Australian L...The yellow-footed rock wallaby also is called the ring-tailed rock wallaby. B...

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Date21 days ago

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Date21 days ago

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 202421 days ago

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 202421 days ago

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2023on 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2023on 04/13/2023

Comments

Mira, The burrows tend to be tight-fitting so that the heat doesn't have too far to go from the perentie, whose body temperature requirements are lower underground than above.

This was very interesting even though this lizard is quite repulsive. But I appreciated learning about it. How fascinating that it uses its throat like that to breathe! And how interesting that it hibernates. But if it needs warmth, where does it find it in burrows?