While we have copies of all of Hildegard's works, the illuminated copy of her theological work, Scivias,is lost.During World War Two it was sent to Dresden for safe keeping, but this was unfortunate, as the Allies bombed Dresden and the city became a fire storm. Compared to the lives that were lost, a book is a small, though regrettable matter.

It is said that she wrote more prolifically than any women of her time, but she wrote more than most men as well. It has been noted [ www.hildegardeofbingen.net ] that while there were always influential women, most wielded influence through their menfolk, but Hildegard was a woman whose influence rested on her accomplishments, and these grew out of her profound religious experience that came to her as visions. For many years she kept the visions to herself until in one vision God told her to write them down and they became the basis of her works of theology.

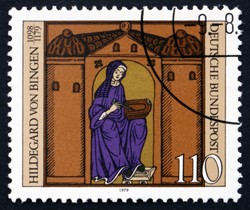

There were three long theological works: the Scivias [Know the Ways] Vitae Meritorum [Of Life's Merits, Liber Divinorum Operum. Each one details her visions, which are then interpreted in terms of her completely orthodox theology. There was nothing uncatholic about Hildegard. Each of these works was written by hand in Latin, and as one early image of her seems to show her as an illustrator it is likely that she was talented in illustration as well. She also wrote the Ordo Virtutum, n allegorical morality play, possibly the first of its kind.

Yet her experience in nursing led to her to take an interest in medicine, and this meant botany, so she wrote works on natural medicine. She broke new ground in writing about women's subjects, one of which was gynecology, so it is likely that she and the nuns were dealing with the health of women in their locality. She also touches on sex, writing on the female orgasm, about which none seems to have written before. Yet she also found time to compose music. She composed within the plainchant traditions of the Catholic Church. Still much of her music survives.

Besides this she found time to found two convents, one at Rupertsberg and one at Eibingen, which replaced an earlier Augustinian foundation. This abbey still survives today.

Along with this came at least four hundred letters to the leading people of the age, including the following: various popes, Emperor Barbarossa, Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, Henry II af England and his queen Eleanor. All these letters give advice. And this is in addition to her being the spiritual leader of an abbey, responsible for guiding the nuns in their religious life.

The energy to work as hard as this derives from her deeply spiritual life, and this sort of work rate is not unusual among saints, for they are energized and motivated by God's power. Yet if you examine the image above you see her bearing a feather, which symbolizes what she saw as her weak body, for she was always conscious of her frailty.

Darkness over the Earth the skies darkened when Jesus was crucified17 days ago

Darkness over the Earth the skies darkened when Jesus was crucified17 days ago

TheThousand Year Gardenon 11/26/2025

TheThousand Year Gardenon 11/26/2025

Women of the Gospelson 10/11/2025

Women of the Gospelson 10/11/2025

Religious Gardenson 08/25/2025

Religious Gardenson 08/25/2025

Comments

The Channel Isles, e.g. Jersey, werebpartvof Normandy and fully integrated into its coin economy. The other isles, such asvthebOrkneys and Man were Norsebterritorybandbtook to cashbasvthe Norse did

Thank you for your comments below, in answer to my previous observation and question.

Isles such as the Outer Hebrides lagging in cash-economizing what they once looked as barter-economics-able makes me mull why they might make that move.

Would present British-Isles-ers of the isles such as Inner and Outer Hebrides, Jersey and Man be among those persevering in traditional beliefs and practices and procrastinating politico-socio-economic change?

I must say that bit was the North West of Scotland, around Loch Maree and in the region of Lochaber that still had a barter economy.

Maybe the Outer Hebrides, but I am uncertain.

Thank you for your comment below, in answer to my previous observation and question.

That highland Scotland "did not have a cash economy until the early nineteenth century" intrigues me.

Might there have been other areas of what merged into the present-day United Kingdom without a cash economy until the above time (or even later)?

The payment would have varied. In some areas it would be in coin, but in others, e.g. highland Scotland, which did not have a cash economy until the early nineteenth century, payment was in kind, with food, other items such as cloth or services.

Thank you for your comment below, in answer to my previous observation and question.

The "local wise women" charging intrigues me.

Their charging and the Church nuns not lets the former perhaps learn more easily about Church healing lore from patients not loaded with healing-services charges than the latter learning from patients less likely to let others freely learn what they logged healing-services charges (and perhaps debts?) for.

Might it be known payment amounts and forms?

Some were church people, though their ministry was not within the church structure. But some were traditional healers. Some paid lip service to Christianity.

Thank you for your comment below, in answer to my previous observation and question.

The phrase "local wise women" intrigues me.

Might these wise women have been Church believers and practitioners or otherwise?

It depends on the area. Sometimes there was a choice of medical specialist, but often the choice was between the church and local wise women, but the church gave service for free,