Liberal scholarship makes out that there is no support for Jesus' divinity in the Synoptic Gospels and that as the Gospel of John, which makes the claim for Jesus' divinity was the last canonical gospel written, it is clear that the belief that Jesus is divine was not part of the original message. Pitrie takes aim at this claim, stating that the divinity of Jesus is present, but couched in Jewish language. He analyses the conceptual background to Jesus' proclamation of God's kingdom, but focuses on three incidents.

Pitrie begins with Jesus' walking on water to point out that the English translation of his words to the Apostles does the gospel no justice. We are told that Jesus meant to pass them by, but said, "It is I." But the phrase "pass them by" in the Moses story denotes what God does when he visits his people. Moreover, the words "It is I" are a mistranslation of ego eimi, which means I am. "I am " is the name for God, which we know as Yahweh and its misspelling Jehovah. This, according to Pitrie is a gentle revelation of who Jesus truly is. A similar revelation comes in the story of the calming of the storm."Who is he that the winds and waves obey him?" For the Jews only God was lord of the winds and the waves. Again, a quiet demonstration that Jesus was more than human.

The words I am are used by Jesus in his self-revelation to Caiphas, who asked Jesus whether he is the Christ. "I am and you will see the Son of Man seated at the right hand of the power and coming on the clouds of heaven." In this we have a coming together of titles that constitutes a self-revelation of a special status. What is more, there are seven I am sayings in John's Gospel that are regarded by liberal scholars as late additions to the Jesus tradition, but Pitrie's observations indicate that they are not Johannine theological elaboration, but are genuine parts of the Jesus story.

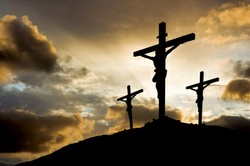

Finally Pitrie turns to the Transfiguration, which liberal scholars dismiss as a post-resurrection experience wrongly placed. But the content of the transfiguration, which contains references to Jesus' coming passion, are inconsistent with this view. Furthermore,Pitrie points out that Moses and Elijah, who appear talking to Jesus. both had experiences of God but did not see him face to face, and as they now see is face the story is hinting that in Jesus they finally see the face of God. Yet another hint of Jesus' divinity in the synoptic gospels.

I have not given an exhaustive account of the book, for there is more in this well-written volume that will repay the reader's time and commitment. Truth is often spoken simply, and in its lucid prose this book speaks the truths of the Christian faith in concise, simple language. I commend it to you

Pilgrimage. A review19 days ago

Pilgrimage. A review19 days ago

Leo the Fourteenthon 05/09/2025

Leo the Fourteenthon 05/09/2025

The Melsonby Hoardon 03/25/2025

The Melsonby Hoardon 03/25/2025

Comments

There is no stated connection. Going without water is limited by human nature.

Thank you for your comment below in answer to my previous observation and question.

So fasting without water can be practiced for "very limited periods."

Might that limited period be 3 hours (for respect to Jesus Christ's time on the Cross?

The church Makes no hard and fast rules on fasting, but after some overzealous devotees fasted without water for periods of more than a day. This resulted in physical illness and sometimes psychiatric hallucinations. So to be safe the church banned fasting without water for anything more than very limited periods.

Thank you for your comment below in answer to my previous observation and question.

The United States once closed businesses between noon and 3 p.m. Good Friday. Some Unitedstatesian churches once followed day-long fasting on that day.

The first practice is non-existent. The second is rare.

What is the Church guideline for extended fasting? Is it absolutely nothing or is it perhaps water or water and bread?

Wilderness survival always first and foremostvneeds water. Bread alone is not moist enough.

Thank you for your comment below in answer to my previous observation and question.

The phrase "bread of life" intrigues me.

Throughout time bread and water invite that possessive prepositional phrase.

Which choice, between bread -- because one survives not on water alone -- and water -- because one survives with it in desert climates -- would be more compelling during Jesus Christ's ministry?

(Would bread have sufficient moisture content for someone to survive without a water source?)

His uttering the words "I am"in the Jewish context indicate that he knew what he was saying. Any and every Jew would have picked up the meaning.

"I am the Bread of life; no one who comes to me will ever hunger." The sentence is easy to translate, with no grammatical complexities and a simple vocabulary. That is what made it stand out from the grammatically complex Latin in which the church documents were couched.

An excellent review. Indeed, the references to Jesus' divinity might have eluded Jesus Himself, if He had not yet, in His human form, come to a full understanding. Of course as a member of the Godhead in Heaven He would always have understood His true nature. It is possible Hos human nature was inspired by His divine nature to choose the words used,

FrankBeswick, What was the statement by Jesus that so impressed you in the Latin that you were translating?