Christian theology was not delivered fully formed by Jesus. Indeed, as a member of the Jewish people he belonged to a people renowned for centuries for their questioning and intellectual vigour. The early Christians were also Jews, who shared in the rich and varied religious and cultural life of Judaism. It was therefore inevitable that the early Christians differed quite vigorously among themselves about the nature and person of Christ. This article looks at how views of Christ differed in the early Christian community.

What Think You of Christ?

by frankbeswick

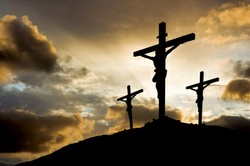

Christian understanding of the significance of Christ evolved over several centuries.

Presence, Charisma and Theology

Various secular thinkers try to reduce Jesus to a single role. He was a story teller, socialist, healer and so on; and what they say is passed off as theology. Erroneously, for to do theology you must be a person of faith reflecting on his/her belief. Without faith you are merely doing history of ideas. Faith in Jesus begins with an apprehension that here was and is someone really special, someone unique who cannot be shrunk to fit into a single category, but one who transcends simple categorisations, one who spoke with authority and exercised spiritual power. Put simply, Jesus was one who knew God intimately and spoke for him. Theology explores what made Jesus unique.

The branch of theology that examines the nature of Christ and his uniqueness is Christology. Over many centuries there has been a division in Christology between low and high Christologies. Low Christology sees Jesus as a man chosen by God. If you read Acts of the Apostles chapter 2, Peter's preaching to the crowds at Pentecost, you see an example of a low Christology in which Jesus is one approved by God and made Lord and Christ. The path to a high Christology is implicit here, because the term Lord denoted the divine being, God, but it seems that Peter's thinking had not evolved into a higher Christology yet. This is understandable, as his preaching [kerygma] was the first instance of a Christian theological statement, so was yet undeveloped.

Instances of low theology persisted among some Jewish Christians for a long time. Adoptionism taught that Jesus was so holy that God adopted him as his son. The weakness here is that a mere mortal cannot become divine, so this would lead to Jesus being less than divine, merely a superior mortal. Another form of low theology which still persists today is Islam's belief that Jesus was a great prophet. Christians believe that Jesus was a prophet [see Luke 24] but more than a prophet.

The Christian sense that Jesus was more than a prophet, rabbi, good man led quickly to the development of high Christology. Two thinkers were instrumental in this. Paul in his letter to the Colossians speaks of Christ as being the image of the unseen God, and in Philippians chapter 2 speaks of Christ as being in the form of God, but emptying himself, a process which he called kenosis. Paul unites this high Christology with the original low Christology in Colossians 1:9 when he moves on to say that for his death on the cross, an expression of kenosis, God raised Jesus high and gave him a name above all other names. It is clear that for Paul Christ's saving work is a sign of a status higher than mere mortal.

The other high Christological thinker was the writer of John's Gospel, a work that is wrongly dated by certain scholars to the second century, but which was written and edited with additions between 60 and the 90s. In John chapter 1, the Prologue he describes Jesus as the Word of God, which the Jews called Dabar, a power that emanates from God to effect his will. But he uses a term from Greek philosophy, logos [word] which was the underlying rationale of creation. Thus Christ is seen as fully human, but also as an expression of God, fully divine, fully human.

Thus high and low Christological themes unite to form a coherent account of Christ's significance. Neither is sufficient by itself.

Divine and Human

From quite early on Christians had recognized that Christ was human and divine, fully God and fully man, having taken a human nature to save humankind. The problem was getting the balance right, because it was easy to err on one side or the other. One aberrant idea was Docetism, which thought that Jesus' human side was merely a front. Jesus' actions were not the actions of a human body, and this meant that he did not really suffer and die. The Church rejected Docetism as it undermined the belief in the saving death of Christ. The Catholic Church insisted that Jesus was fully human as well as fully divine. Docetic beliefs were common among Gnostics, adherents of a belief system that elevated the spiritual to the extent that they downplayed the material world, sometimes claiming that matter was the product of a lower being. So how could a holy being like Jesus have a material body. Docetic tendencies are still evident among those Christians who think that Jesus had no human feelings or needs.

One heresy that was trinitarian in character was Modalism and its derivative Sabellianism. Modalism was the belief that Father, Son and Spirit are different modes of God's existence. The Church rejected this on the grounds that mode is not a term strong enough to express the difference of persons in the Trinity. Sabellianism is the belief that Father, Son and Spirit are three successive modes of God's existence. Thus Christ was God manifest at one time, but now he is manifest as the Holy Spirit. This belief flies in the face of the fact that Jesus was in relation to the Father, not identical to him.

A major heresy that needed the Council of Nicaea to resolve was Arianism. Arius, a priest from Alexandria in Egypt, taught that Christ was a created being, the greatest of all created beings. The implication is that he is not divine. This position is inconsistent with the tenet of faith that to save humankind Christ needed to be fully God and fully human. The resistance to Arius, who was supported by many influential people, was led by Athanasius of Alexandria, and culminated at Nicaea inn 325 when the Church taught that the Son was "begotten not made." This meant that while the Son, the Second person of the Trinity, derives from the Father he was eternally present with the Father and there was no time when he was not.

The Council of Nicaea took the old Apostles' Creed, which stated the basic tenets of Christian belief and in the section devoted to Jesus, the Son, added "Begotten not made." This meant that the Church now used the Nicene Creed. The term is still used, even though additions were made later, as you will see in the next section. A key term adopted at Nicaea was homousios [Greek 'omos, meaning same, ousios, substance] with the Father and was therefore divine. This was to differentiate orthodox Christians from those who said that Christ was homoiousos [of like substance.] The modern translation of the creed renders homousios as consubstantial with the Father.

Two Non-orthodox Churches

While the Orthodox Church is the name for a large federation of churches, the term orthodox signifies those Christians who accept the teachings of the councils of Ephesus in 430 and Chalcedon in 451. Two churches that still survive today do not accept these two councils and are thus accounted non-orthodox. These are the Nestorians and the Monophysites, the latter being known as the Copts, who are strongly represented in Egypt and Ethiopia. The problem was again to get the language of the two natures in Christ right. This was not a minor problem, as language shapes the way in which we look at the world and the way that we think. We have to get it right.

Nestorius taught that the divine and human natures in Christ were united in moral union. Nestorius did not want to deny the divinity of Christ, or indeed the humanity, but moral union was two weak a term to sustain the doctrine of two natures in one person, and it suggested that Jesus was a man in whom a divine being dwelt and acted and that he was two persons in one body. This belief was condemned at the Council of Ephesus. Nestorian Christianity is known as Syriac Christianity, as it was strongest in Syria and Iraq, but it flourished for centuries outside the Roman world. In the 1930s a large number of Nestorians went over to the Roman Catholic Church.

The Monophysite Church is the stronger of the two churches. It is sometimes known as the Miaphysite Church because Mia means one in Greek. This was an unnecessary split because it was due to mutual is misunderstanding of terminology and a great deal of ecclesiastical politicing.The trouble came with a sentence from St Cyril of Alexandria,the one incarnate nature of the incarnate Word. There was a difference in meaning of nature [ousios] between theologians between the Alexandrians, who meant reality, and others, for whom it meant substance. Cyril was accused of thinking that Christ was a mix that was neither God nor man, which was never his intention. but positions had hardened and social unrest was developing. The Council of Chalcedon was called to settle the differences, but as usually was the case splits became entrenched. The Monophysite faction refused to accept the council and split off from the mainstream. In recent years talks have taken place that have accepted that the split was mistaken, but the schism remains unhealed.

Thoughts

I have given a brief account of theological disputes in early Christianity. It is a brief history of religious ideas. But questions of faith cannot be resolved by historical methods. When speaking of Christ everyone is challenged to decide for their selves. He was a unique and powerful character whose presence is still felt long after his time. His story raises vital questions about the relationship between God and humanity. We all must decide whether we are for or against him. What we decide really matters. Neutrality is not enough. The ancient question, what think you of Christ, is still an urgent one.

You might also like

Who was JesusTo understand Jesus you must realize that he was a mystery that theology trie...

Ministry in the church:women bishopsThe long awaited decision to have women bishops is major progress.

Darkness over the Earth the skies darkened when Jesus was crucified18 days ago

Darkness over the Earth the skies darkened when Jesus was crucified18 days ago

TheThousand Year Gardenon 11/26/2025

TheThousand Year Gardenon 11/26/2025

Women of the Gospelson 10/11/2025

Women of the Gospelson 10/11/2025

Religious Gardenson 08/25/2025

Religious Gardenson 08/25/2025

Comments

I have answered this question already.

I think that whether there remained communication between the now sundered groups varied with the individual

The computer crashed before I completed another component of my comment below.

The conversions almost 100 years ago perhaps affected extended and nuclear families and their friends.

Is it known whether those who adhered to Nestorian beliefs and practices associated with those who accepted Church beliefs and practices?

Thank you for your comment below in answer to my previous observation and question.

Modern Nestorians appear so vulnerable in their biogeography and in their numbers.

Is it known whether the modern descendants of those who left Nestorian beliefs in the 1930s have any helping, humanitarian interactions with modern Nestorian believers and practitioners?

Modern Nestorians tended to concentrate in North Iraq in the plains of Nineveh, but some dispersion has been caused by Islamic State.

Thank you for your comment below in answer to my previous observation and question.

The present-day Nestorians must be religious minorities almost undetectably small wherever they might be.

Would Nestorian believers tend to be a tight group of family and friends whose beliefs wend their way from generation to generation rather than through proselytizing?

The Assyrian church was Nestorian in theology, that is that they believed that the two natures in Christ were merely in moral union, which the Catholic Church says did not give a strong enough accounte of the oneness of Christ. But in theb1930s 80 per cent of the Nestorians became Catholic

Thank you for your comment below in answer to my previous observation and question.

English Wikipedia associates the Assyrian Church of the East with apostles Bartholomew and Thomas as its founders.

Is the Assyrian Church the way that the latter duo instituted it or is its difference from the Catholic Church something that neither one implemented or invoked?

No specific event. Conversions to the Chaldean rite of the Catholic Church have been happening on and off since the 1550s.

Was there some known event that prompted Nestorian conversions to Roman Catholicism in the 1930s?