New World avian native Passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) favored chestnuts in their diet and sheltered in American Chestnuts.

Martha, last-known passenger pigeon, died at Cincinnati Zoological Garden on September 1, 1914; her taxidermied body currently is on display through September 2015 via Once There Were Billions exhibit at Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

National Museum of Natural History, National Mall, Washington DC: Ph0705, CC BY SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Martha,_the_last_Passenger_Pigeon._Natural_History_Museum,_June,_2015._Digital_photo,_cropped_and_brightened.jpg

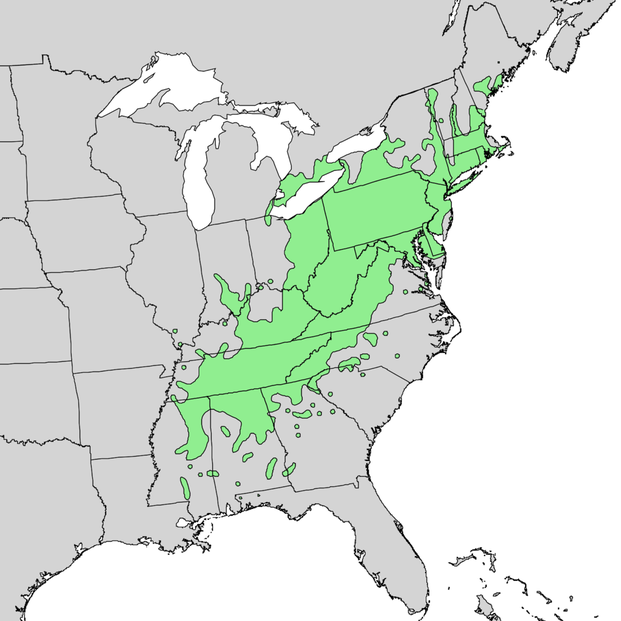

The altitude-specific range of the American Chestnut (Castanea dentata) reveals the New World native's affinity for the Appalachian Mountains of eastern North America.

Elbert L. Little Jr., Atlas of United States trees, volume 4 (1977), Map 27-NE: USGS Geosciences and Environmental Change Science Center, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Castanea_dentata_range_map_2.png; Not in copyright, via Biodiversity Heritage Library @ https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/42043928

1943 photo of dead American Chestnut; death was caused by chestnut blight (Cryphonectria parasitica)

"chestnut blight or canker (Cryphonectria parasitica) (Murrill) M.E. Barr": USDA Forest Service - Northeastern Area Archive, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org, CC BY 3.0, via Forestry Images @ https://www.forestryimages.org/browse/detail.cfm?imgnum=1396146; Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cryphonectria_parasitica_trees_dead.jpg

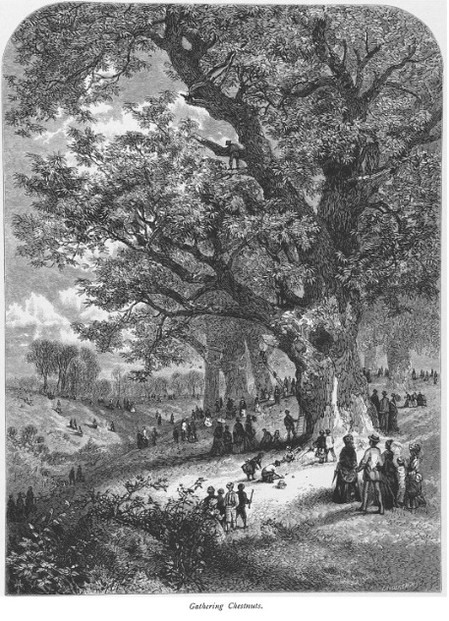

American Chestnuts were treasured both as backdrops and as mainstays for social activities from colonial times through the 19th century.

"Gathering Chestnuts"; engraving of scene at Philadelphia's Fairmount Park by James W. Lauderbach (1830-1898)

Art Journal, New Series, vol. 4, issue 37 (1878), page 2; Public Domain, via JSTOR @ https://www.jstor.org/stable/20569163; via Internet Archive @ https://archive.org/details/art-journal-us_1878_4_37/page/2/mode/1up

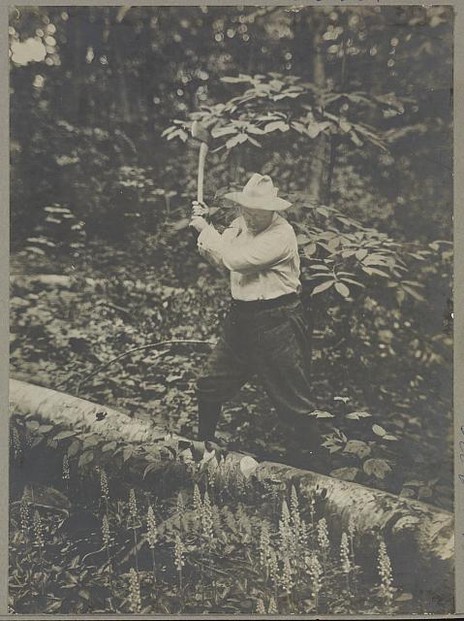

26th US President Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt chops a fallen tree at Sagamore (Algonquin: "Chieftain") Hill, his beloved estate that served as Summer White House during his presidency (September 14, 1901 – March 4, 1909).

In 1910, after leaving the presidency, Theodore Roosevelt dropped his captivating, ebullient demeanor as he sadly chopped American Chestnuts stricken by the blight at Sagamore.

Sagamore Hill, Cove Neck, North Shore of Long Island, New York; ca. September 11, 1905: No known restrictions on publication, via Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division @ https://www.loc.gov/item/2009631368/

America poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807–March 24, 1882) immortalized American Chestnut's iconic role in US cultural history via opening lines of The Village Blacksmith (1840): "Under a spreading chestnut tree the village smithy stands".

1840 sketch by H.W. Longfellow of the American Chestnut on Brattle Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts, that he memorialized in his poem; when the tree was cut down, the poet was gifted with a chair made from its wood.

Longfellow's Life and Legacy by NPS Longfellow National Historic Site, p. 22: Public Domain, via National Park Service @ https://www.nps.gov/long/learn/education/upload/Longfellow-s-Life-Legacy.pdf

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Comments

President Theodore Roosevelt advised conversing softly even as one carried -- just in case... -- a big stick.

The afore-designated president described the American chestnut as his favorite tree.

So might some American-chestnut wood have made that weaponizable accessory?

For those asking about the chestnut tree sketched by American poet Henry Wadsworth Longellow (Feb. 27, 1807–March 24, 1882) and displayed as last image in this post:

The poem's chestnut tree towered over the smithy, also known as forge, that served as the workshop, located at 54 Brattle Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts, for Longfellow's neighbor, blacksmith Dexter Pratt (May 18, 1801-Oct. 4, 1847).

The widening of Brattle Street in 1871 inconveniently placed the chestnut tree "in the street, just beyond the curb," according to "Second Only to the Washington Elm in Eager Tourist Interest Is the Site of 'The Spreading Chestnut Tree' Made Famous in Longfellow's Poem," an article published Saturday, April 7, 1923, in "A Review of Beautiful and Historic Cambridge" section of The Cambridge Tribune (vol. XLVI, no. 6, page 6; URL @ https://cambridge.dlconsulting.com/?a...). Despite the community's "spirited" opposition, the tree was cut down "bright and early, before five o'clock one April morning" in 1876. "The school children of Cambridge presented Longfellow with an armchair made of the tree and he made this the subject of a poem."

The armchair was designed by architect and architectural scholar William Pitt Preble Longfellow (Oct. 25, 1836-Aug. 3, 1913), son of the poet's older brother, Stephen Longfellow (Aug. 14, 1805-Sep. 19, 1850), according to "The Chestnut Chair, ca. 1876" record on the Maine Memory Network website (https://www.mainememory.net/record/15476).

The chair's design included an excerpt from the opening and closing lines of the fourth stanza from Longfellow's eight-stanza poem, "The Village Blacksmith":

"And children coming home from school

Look in at the open door;

. . . . ,

. . . ,

And catch the burning sparks that fly

Like chaff from a threshing floor."

The gifting schoolchildren commissioned Boston-based cabinet maker H. Edgar Hartwell to make the chair, according to "Collections From Massachusetts National Parks" on the Google Arts & Culture website (https://artsandculture.google.com/sto...).

The commemorative chair was presented to the poet on his 72nd birthday. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow expressed his appreciation for the gift in a poem, "From My Arm-Chair."

American chestnuts angle into delicious alcoholic drinks.

Has anyone had chestnut liqueur or such cocktails as chestnut old fashioned?

My comment below about the layers between the outermost cover and the innermost nutmeat causes me to consider ways of culling the nutmeat from such a somewhat scary cover as that of the American, the hybrid, other chestnuts.

Couldn't it be compelling to count the ways by which one painlessly, quickly, successfully culls the chestnut nut and its seeds?

The green, outer, soft layer to the dark shell to the light nutmeat of the black walnut is not edible.

Is the dark, hard shell between that green layer and the light-colored nut edible?

The fourth in-text image always causes me to consider American chestnuts as backdrops and mainstays to social activities and to socio-economic production.

All tree parts contributed to individual and neighborhood needs.

The wood delivered durable functional and ornamental products. The leaves figured in medicinal teas and in soothing hot drinks. The nuts generated fresh, raw grab-and-go snacks and baked, cooked, fried, grilled foods.

I know from the hybrid chestnut alongside the south side of the house. I love gathering and processing plant parts even as I always make sure that wildlife sentients munch them too.

Wouldn't it be wondrously wonderful to work up a chestnut recipe book?

WriterArtist, Thank you for visiting and writing so wonderfully about trees in general and our world's chestnut trees in particular,

You're absolutely correct.

The chestnut tree in the south lawn houses rare eastern bluebirds, among my favorite sentient avian species.

Within the last few years arboricultural researchers published their findings that trees keep on enriching the soil and the soil food web even when they are no more than above-ground stumps and below-ground roots.

Hi DerdriuMarriner - The pictures you have posted speak volumes of the Chestnut trees. The American Chestnut tree looks majestic in the full view. All big trees are a boon to the Nature, for they house several and some rare species of birds. If trees go extinct, so do the species dependent upon the tree. Even after a tree dies, it is used as fuel and in the forest it serves to enrich the soil. I find joy in all kinds of trees, just looking at them brings me peace.

candy47, It must have been one of the chestnuts that Virginia Tech Professor Gary Griffin predicted would outlive the blight, which affected trees in record time! Do you have any pictures or is this just a beautifully fond memory that you're one of the lucky ones to have? It's fun to reminisce about chestnuts -- ;-] -- over tea!

There was a beautiful chestnut tree in front of our house in the 1950's. The tree has been gone a long time now. Thanks for the morning read with my tea!