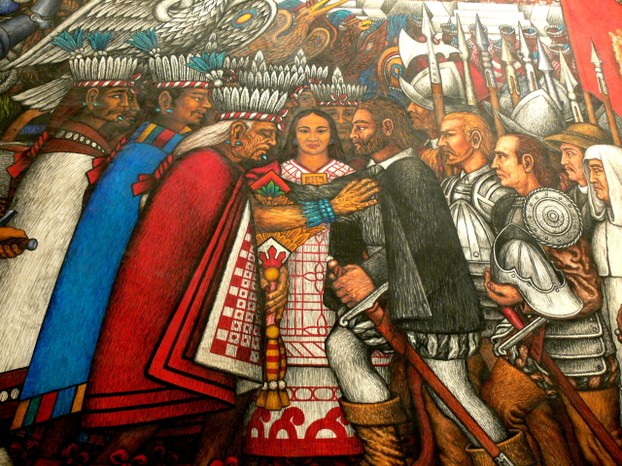

"se inicia el mestizaje aqui en tlaxcala acuerdo de paz y recepcion" ("Mestizoization began here in Tlaxcala; peace agreement and reception"): mural by Tlaxcalan muralist Desiderio Hernández Xochitiotzin (February 11, 1922 – September 14, 2007)

Malinche (center) with Hernán Cortés (right) and Tlaxcalan leaders (left)

Palacio de Gobierno, Tlaxcala City, Tlaxcala state, east central Mexico: Wolfgang Sauber, CC BY SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archivo:Tlaxcala_-_Palacio_de_Gobierno_-_Verhandlungen_Spanier_-_Tlaxcalteken_2.jpg

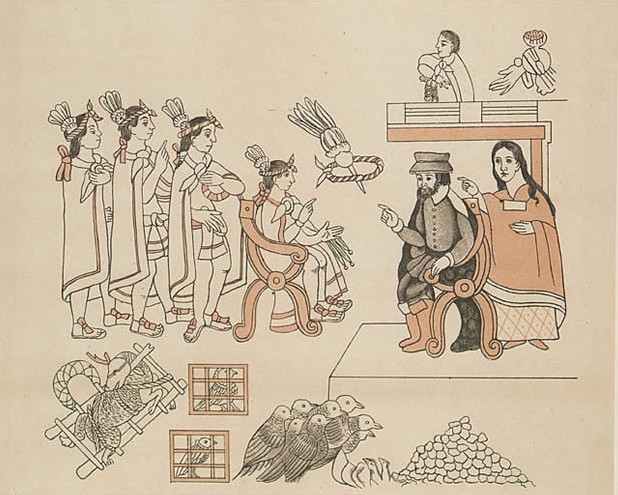

Historic meeting of Cortés and Moctesuma: doña Marina alongside Hernán Cortés

"Tenochtitlan. Tierra del nopal. Entrada de Hernan Cortes, la cual se verificó el 8 de noviembre de 1519"; ca. 1890 facsimile of paintings by artists for Tlaxcalan royal houses ca. 1560

Lienzo de Tlaxcala (Linen of Tlaxcala); sixth of approximately 80 images in a series of 42 colorplates: Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cortez_&_La_Malinche.jpg

Aztec calendar stone known as Stone of the Five Suns or Eras: basaltic carving, which includes sun and time symbols, was buried during Spanish Conquest of Mexico, ca. 1520, in Zócalo, main Aztec ceremonial center in Tenochtitlan.

Stone was rediscovered December 17, 1790, during repairs to Metropolitan Cathedral of the Assumption. Consecrated in 1656, construction was ordered by Hernán Cortés after tearing down of nearby Aztec Templo Mayor (Main Temple).

Museo nacional de Antropología e Historia (National Museum of Anthropology and History), Mexico City: Anagoria, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1479_Stein_der_fünften_Sonne,_sog._Aztekenkalender,_Ollin_Tonatiuh_anagoria.JPG

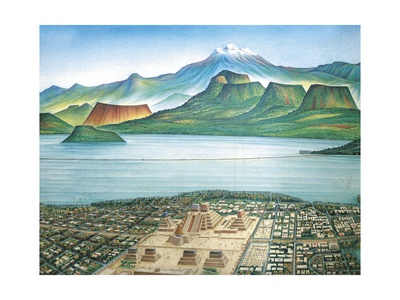

Pyramid of the Sun, stairway to the top: Sun was important power and symbol in ancient Mexico.

Teotihuacan; designated as UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987: Mariordo (Mario Roberto Durán Ortiz), CC BY SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pyramid_of_the_Sun_stairway_Teotihuacan_03_2014_MEX_7972.JPG

Zia Sun Symbol on Flag of New Mexico: Aztecs were not alone among indigenous American peoples in belief in Sun as sacred symbol; New Mexico's indigenous Zia tribe esteemed their own Sun Symbol.

Deming, central Luna County, southwestern New Mexico: SteveStrummer, Public Domain (CC0 1.0), via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flags_flying,_U.S._and_New_Mexico,_February_2014.jpg

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Comments

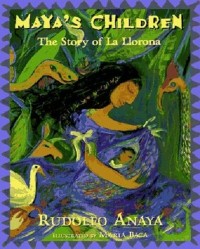

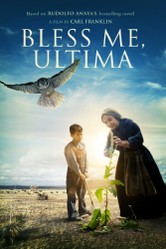

CruiseReady, Thank you for liking this review! Rudolfo Anaya has a talent for lifting readers up -- as in his beautiful story "Bless Me, Ultima" -- even when he touches upon what is disappointing or sad in life. The book is told so beautifully and offers such cultural and historical insights that it is worth the read and re-read...as I do with this book and with the author's other children's books. Spanish-speaking parents use the story of the crying woman -- not of scary monsters like in horror films (which I tend to avoid) -- to encourage their children to be home before dark and to be careful of strange behaviors and people outside their known circle of family, friends, and peers.

What a beautifully illustrated article! After reading it, I find myself thinking I would like to read this children's book myself, even though it sounds as if it has some pretty sad elements.

Mira, New Mexico lives up to its nickname as The Land of Enchantment. Me, too, I also love the Zia Sun Symbol on New Mexico's beautiful state flag.

I appreciate the compliment on the illustrations in my articles. Images entertainingly convey information and effectively reinforce education.

I especially value your compliment on this article because Rudolfo Anaya is a living treasure.

I love that sun symbol on the flag. You always illustrate your articles so nicely. Thank you for sharing all this with us. The story is also interesting.