So much of what we eat these days is manufactured. We don’t know the process, how much time is taken, the cleanliness of the facilities, nor do we know much about just how the ingredients are put together even though they are listed on the packaging. This, the ingredient list, is another “bone of contention” for me. Usually half of what is listed is there to preserve the bread. The longer it lasts on the shelf, the better for the manufacturer. Bread that can sit out without going bad is much more profitable than bread that will spoil in a week or less. Many of us don’t want to eat those chemicals though. I’m one of them.

Bread Making for the Love of It

by LiamBean

May 14, 2013: This series of articles will be about making yeast breads; an art that is falling by the wayside.

Foreward

This series of articles will be about making bread, by yourself, with yeast as the leavening. It is a rewarding thing to do. Few things cooked in the kitchen have quite same ability to stir the heart and water the mouth. The aroma of rising bread or bread fresh out of the oven is like ambrosia; at least it is to me.

Yeast bread is not that difficult. Yes, it takes time, but most of that time is spent simply waiting for the dough to rise. Anyone can do that. It requires you to do nothing for set periods of time. The problem comes in having to do something with the risen dough after a certain amount of time. That could be twenty minutes, eight hours, twelve hours, or even twenty four hours depending on the type of bread you are making.

Almost all bread is simply three ingredients. Flour, water, and yeast. Usually though I’ll also use sugar or honey, no more than a tablespoon of either, to speed the yeast rising process. Yeast will certainly cause dough to rise without the sugars, but adding some sugar will really give that yeast a boost. The only other ingredients I use is salt for five ingredients total. The salt is there, in small quantities, to enhance the flavor of the dough, but it has other effects as well.

A Brief History of Bread

As far as we know it was the Egyptians who came up with adding yeast to flour to make bread. They used it for making both bread and beer. As a means of giving flour the ability to rise, the use of yeast is at least 5,000 years old. Unlike today, brewers and bakers had to save back an unbaked bit of dough containing this yeast. This bit was added to the new dough and a bit saved from the new batch of dough to use again. Over time the yeast selected this way became better at fermenting and forming gas bubbles in both beer and bread.

Note: There is a saying that bread is sold beer and beer is liquid bread.

Before that time most flours were made with einkorn wheat, barley, or rye and none of these early grains had enough gluten in them to make a decent leavened loaf. Gluten is a protein that causes the dough to bind together. This is an important quality in bread. With yeast fermenting and producing gas to form small bubbles in the dough, the sticky quality of the dough, imparted by gluten, give the bread its texture. So though Egypt came up with yeast bread there had to be advances in wheat as well to form the bread we know today.

Prior to the Egyptians introducing yeast, most bread was flat and any rise was due entirely to the heat used in cooking or the addition of other ingredients (such as egg) to give it some rise. Even then bread tended to be tough, rubbery, and chewy.

Pure Ingredients are Important

Like anything else we eat, the ingredients that make up our food are very important. In the case of bread the proper type of flour, pure water, and reliable yeast are necessary. Salt and sugar are less important considerations because they, by their very nature, are relatively pure. For example bacteria cannot grow on anything that is too salty or has an abundance of sugar. Still, I prefer to use sea salt and unrefined sugar. If I use honey I’ll choose clover honey. None of these three; salt, sugar, or honey, are in high enough quantities to affect the taste much though salt is certainly a flavor enhancer.

In the beginning your flour and water are not that important. You are simply trying to learn how to combine the two in the proper proportions to make bread. For that reason a good, general purpose flour should be a good enough start and tap water pure enough for our purposes. You will still get a decent loaf of bread with these two, less than perfect, ingredients. The yeast is also important, but most markets carry just one brand and is reliable if not incredibly expensive for what you are getting. In time you may want to buy your yeast in “bulk.”

As you gain experience you may want to start adding whole wheat flour, for its fiber and nutritional benefits, and pure filtered water to improve the overall texture and flavor of the loaf. Purer water does have an effect on how well the yeast rises.

Flour should always be sifted, even if you are measuring by weight rather than volume. Sifting “fluffs” up the flour and improves its ability to work with water and yeast. The good news is that the sifting can be done after the measuring or weighing of the flour.

Finally, I avoid recipes that insist that the bread flour come in set volumes. Measuring by volume, does not account for flour’s hydrophilic nature. It absorbs water just sitting on the shelf. For that reason I always recommend weighing the flour. It is the liquid you want to measure by volume. In all cases I will provide units of measure in pounds and grams for flour and ounces and milliliters for fluids.

The Importance of Yeast and Rise

The production of bubbles is caused by the release of carbon dioxide into the dough as the yeast digests the sugars. If the dough is properly mixed, the yeast is also well distributed throughout the dough. This means those bubbles tend to be smaller and more consistently distributed throughout the dough.

Yeast also produced alcohol as it digests sugars. This is not a huge amount of alcohol, but enough to impart some flavor to the dough. The yeast itself adds some favor too.

The Importance of Salt, Sugars, and Temperature

Salt does not just enhance the flavor of the bread it also helps to control just how active the yeast is. To put this another way the more active the yeast, the more springy and spongy the bread. On the other hand if we are looking for a finer texture we may want to use the salt sooner during the initial rising process.

For this reason some recipes call for the salt to be added as a dry ingredient and some for the addition of the salt to the dough once mostly mixed.

Sugars are also an important consideration. Some recipes should use no sugar or just the bare minimum. Others will call for sugar as a pre-fermentation ingredient. Sugars cause the yeast to get a jump start on the fermentation process and this, in turn, shortens the rising time. Like salt, sugar affects the rise. Sugar has another function as well. It affects the brownness of the crust and its quality of crispness.

Temperature is also quite important. Temperatures over 115° F (or 47° C) will kill or cripple the yeast thus preventing rise. Interestingly enough, yeast can be frozen and some recipes call for the pre-ferment to be chilled or refrigerated for different effects on the final dough. Yeast will continue to ferment, though slowly, if it is chilled.

The Importance of Time

Time is another consideration. If the yeast is not given time enough to work its magic, there is little point in using it begin with. Many recipes call for a preferment time of twenty minutes. This is enough time to give the yeast a good running start at fermentation and prove to the baker that it is working. This is why it’s called “proofing” by the way.

Almost all yeast breads need three rising periods. The proof, first rise, and second rise. There is always kneading or mixing between these rises. So over all, three rises, and two mixes or kneads.

The proof is usually one to two hours. The first rise is usually as little as twenty minutes to two hours. The second rise is where the most deviation comes from. Breads that are designed to have large voids and be very springy work best if the second rise is eight to twelve hours in a chilled environment, such as your refrigerator. Pan loaf breads, on the other hand, will have a final rise of no more than two hours and often no more than an hour usually right in the pan used for baking.

Time also has an effect on flavor. The more time yeast has to work in the dough the sourer the flavor notes produced. Less rise time produces fewer of these sour notes in flavor.

Flours: Whole grain, whole wheat, unbleached, and bleached

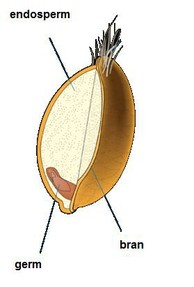

Flour is one of those things that has been modified endlessly. In the early eighteenth century flour was widely exported throughout the English world. Processing, shipping, and shelf storage all had a huge impact how long the flour would last. After nine months a sack of flour would go rancid making anything made with it unpalatable. With a combination of sea shipping and rail, a shipment of flour to India might be on the verge of going bad just as it got there. To overcome these difficulties Victorian era millers removed the germ (and later the bran) to improve travel and shelf life. The idea was to remove the parts of the wheat berry that lead to spoilage. These high spoilage components consisted of the germ and the bran which contain fatty. The Victorians, not knowing any better, took most of the nutrition out of the flour in the process.

Flour is one of those things that has been modified endlessly. In the early eighteenth century flour was widely exported throughout the English world. Processing, shipping, and shelf storage all had a huge impact how long the flour would last. After nine months a sack of flour would go rancid making anything made with it unpalatable. With a combination of sea shipping and rail, a shipment of flour to India might be on the verge of going bad just as it got there. To overcome these difficulties Victorian era millers removed the germ (and later the bran) to improve travel and shelf life. The idea was to remove the parts of the wheat berry that lead to spoilage. These high spoilage components consisted of the germ and the bran which contain fatty. The Victorians, not knowing any better, took most of the nutrition out of the flour in the process.

Flour without the germ or bran is referred to as “white” or refined flour.

Bleached wheat flour has the additional step of chemically altering the flour to enhance its “whiteness.” To bleach a flour the miller uses one of four chemicals to whiten it. These are:

- Potassium bromate which improves gluten, but does not bleach

- Benzoyl peroxide which does bleach, but does not act to improve gluten

- Ascorbic acid which improves gluten development, but does not bleach

- Chlorine gas which both bleaches and matures the flour

Bromated (potassium bromate) wheat has been outlawed in the United States and many other countries. The only bleaching agent allowed in the European Union is ascorbic acid which is the main component in vitamin C tablets.

Self rising flour has a ratio of baking powder and salt in it. Since it is self-leavening it is not good for yeast breads.

Unbleached flour is flour made up of the whole grain; consisting of the milled endosperm along with the bran and germ. It is also called “Whole Wheat” flour. There is some confusion about this with some people swearing that “unbleached” simply means the flour has not been bleached while the germ and bran have been removed. Others claim that unbleached means only that the flour has not been bleached, but that it is the whole grain. This later is true.

Refined flour is flour where both the bran and germ have been removed, but has not been bleached. It is also called “white flour.”

Refined or unbleached flour is what you very likely want to use.

To recap:

- White flour has had the bran and germ removed; it is not bleached

- Refined flour is another name for white flour

- Bleached flour is refined flour that has also been chemically bleached

- Enriched flour is bleached flour with vitamins and minerals added back into it

- Unbleached flour is whole wheat; it has the bran, germ, and endosperm milled together

- Whole Grain flour is unbleached flour

- Whole Wheat flour is, by all rights, unbleached flour

Notes About Wheat

White wheat, red wheat and winter wheat are all used to make flour. Most companies use red wheat as a flour base. White wheat is a bit more expensive and winter wheat has a very tight growing season though it is typically thought to be the best for cake flour. Red wheat has the most protein in the form of gluten, followed by winter and then white. Almost all manufacturers, unless they note otherwise, use red wheat.

Bread Making by Hand

In the confines of this article handmade means no machine assistance. It means that the mixing of the flour and other ingredients and the kneading of the dough are all done by hand. Times required for the various steps in bread making do not change only the method of mixing and kneading the dough.

Kneading typically involved folding the dough in half, pressing the dough flat, and folding in half again, but this time at a right angle to the last fold. The process is a form of mixing when the ingredients are already mixed.

Bread Making by Machine

In the confines of this article this means using a stand mixer and dough hook to knead the dough. This is the method I use most often. Because kneading is a two step process the first machine knead takes two minutes followed by a twenty minute rest. The second kneading last two to five minutes.

You know the machine kneading is complete when the dough no longer adheres to the side of the bowl and 95% of it has “climbed” up on the hook. Once this second kneading is complete the dough should rest for from two hours to a full day depending on the kind of bread you are making.

You might also like

Ciabatta - Italian "Slipper" BreadCiabatta is Italian for slipper. This is fitting since the finished loaf is s...

Rustic Boule BreadThis is a simple recipe for rustic, country style bread. It is called Boule, ...

Crêpes and Crêpe Disheson 09/14/2016

Crêpes and Crêpe Disheson 09/14/2016

About Me - Liam Beanon 11/28/2014

About Me - Liam Beanon 11/28/2014

About Ebolaon 11/08/2014

About Ebolaon 11/08/2014

Comments