Bassarova, M.; Archer, M.; and Hand, S.J. December 20, 2001. “New Oligo-Miocene Pseudocheirids (Marsupialia) of the Genus Paljara from Riversleigh, Northwestern Queensland.”Memoirs of the Association of Australasian Palaeontologists 25:61-75.

Bisby F.A.; Roskov Y.R.; Orrell T.M.; Nicolson D.; Paglinawan L.E.; Bailly N.; Kirk P.M.; Bourgoin T.; Baillargeon G.; Ouvrard D. (red.) 2011. Species 2000 & ITIS Catalogue of Life: 2011 Annual Checklist. Species 2000: Reading, UK. Retrieved on April 1, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.catalogueoflife.org/annual-checklist/2011/search/all/key/pseudochirops+cupreus/match/1

Boelens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; and Grayson, Michael. 2009. The Eponym Dictionary of Mammals. JHU Press.

Boudet, Ch. 10 January 2009. "Species Sheet: Coppery Ringtail." Mammals' Planet: Vs n°4, 04/2010. Retrieved on April 1, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.planet-mammiferes.org/drupal/en/node/38?indice=Pseudochirops+cupreus

Conn, Barry J.; and Damas, Kipiro Q. 2005. Guide to Trees of Papua New Guinea: Tree Descriptions. National Herbarium of New South Wales and Papua New Guinea National Herbarium. Retrieved on April 1, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.pngplants.org/PNGtrees/

Duff, Andrew; and Lawson, Ann. 2004. Mammals of the World: A Checklist. Yale University Press.

Earle, Christopher J. (Editor). The Gymnosperm Database. Retrieved on April 1, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.conifers.org/index.php

Flannery, Timothy F. 1994. Possums of the World: A Monograph of the Phalangeroidea. Chastwood, Australia: GEO Productions in association with the Australian Museum.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the United Nations Environment Programme. 1984. “Part II Country Briefs: Papua New Guinea.” Tropical Forest Resources Assessment Project (in the framework of the Global Environment Monitoring System – GEMS) – Forest Resources of Tropical Asia. UN 32/6.1301-78-04 Technical Report 3. Rome, Italy: Publications Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, first printing 1981, second printing 1984. Retrieved on April 1, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.fao.org/docrep/007/ad908e/ad908e00.htm

- Available at: http://www.fao.org/docrep/007/ad908e/AD908E22.htm

Food and Agriculture Organization Forest Harvesting, Trade and Marketing Branch. 1998. “Appendix 1. List of Tree Species.” Forest Harvesting Case-Study 15: Forest Harvesting Operations in Papua New Guinea, The PNG Logging Code of Practice. Rome, Italy: Publishing and Multimedia Service, Information Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved on April 1, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.fao.org/docrep/004/Y2711E/y2711e00.htm#TopOfPage

- Available at: http://www.fao.org/docrep/004/Y2711E/y2711e12.htm

Gansloßer, Udo. 2004. "Coppery Ringtail: Pseudochirops cupreus." P. 123 in Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia, Second Edition. Volume 13: Mammals II, edited by Michael Hutchins, Devra G. Kleiman, Valerius Geist, and Melissa C. McDade. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group, Inc., division of Thomson Learning Inc.

Gould, John. 1863. Mammals of Australia. Volume I. London: John Gould.

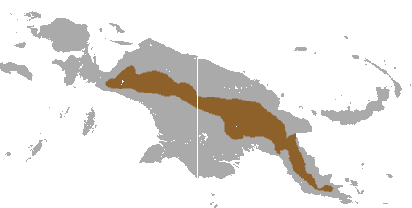

Helgen, K.; Dickman, C.; and Salas, L. 2008. "Pseudochirops cupreus." In: IUCN 2013. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. Retrieved on April 1, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/18505/0

Hoffman, Carl. Savage Harvest: A Tale of Cannibals, Colonialism, and Michael Rockefeller's Tragic Quest for Primitive Art. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2014.

Hume, Ian D. 1999. Marsupial Nutrition. Melbourne, Australia: Cambridge University Press.

Kerle, Jean Anne. 2001. Possums: The Brushtails, Ringtails and Greater Glider. Sydney: University of New South Wales Australian Natural History Series. Retrieved on April 1, 2014.

- Available at: http://books.google.com/books?id=YDM0hjAwchUC&lpg=PT65&dq=Petropseudes%20dahli&pg=PT66#v=onepage&q=Petropseudes%20dahli&f=false

Menkhorst, Peter; and Knight, Frank. 2001. A Field Guide to the Mammals of Australia. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Menzies, James. 5 June 2011. A Handbook of New Guinea’s Marsupials and Monotremes. University of Papua New Guinea Press.

Meredith, Robert W.; Mendoza, Miguel A.; Roberts, Karen K.; Westerman, Michael; and Springer, Mark S. March 2, 2010. “A Phylogeny and Timescale for the Evolution of Pseudocheiridae (Marsupialia: Diprotodontia) in Australia and New Guinea.” Journal of Mammalian Evolution17(2):75-99. Retrieved on April 1, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2987229/

Myers, P.; Espinosa, R.; Parr, C.S.; Jones, T.; G. S. Hammond, G.S.; and T. A. Dewey, T.A. 2014. "Pseudochirops cupreus: Coppery Ringtail Possum (On-line)." The Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved on April 1, 2014.

- Available at: http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Pseudochirops_cupreus/classification/

Nowak, Ronald M. 1999. Walker's Mammals of the World, Sixth Edition. Volume I. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Nowak, Ronald M. 2005. Walker's Marsupials of the World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Petocz, Ronald G. 1 October 1989. Conservation and Development in Irian Jaya: A Strategy for Rational Resource Utilization. Brill Academic Publishers.

"Pseudochirops cupreus." Digital Morphology: A National Science Foundation Digital Library at University of Texas, Austin. Retrieved on April 1, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.digimorph.org/specimens/Pseudochirops_cupreus/

"Pseudochirops cupreus: Coppery Ringtail Possum." Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved on April 1, 2014.

- Available at: http://eol.org/pages/323835/details

"Pseudochirops cupreus (Thomas, 1897)." GBIF Backbone Taxonomy: Animalia>Chordata>Mammalia>Diprotodontia>Pseudocheiridae>Pseudochirops. Global Biodiversity Information Facility. Retrieved on April 1, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.gbif.org/species/2440077

Ride, W.D.L. 1970. A Guide to the Native Mammals of Australia. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Schaefer, Albrecht G. “New Guinea Forests: Still the Tropical Paradise.” World Wildlife Global>What We Do>Priority Places>New Guinea>The Area>Ecosystems>Forests. Retrieved on April 9, 2014.

- Available at: http://wwf.panda.org/what_we_do/where_we_work/new_guinea_forests/area_forests_new_guinea/new_guinea_forests_ecosystems/forests_new_guinea/

Sillitoe, Paul. 2013. Managing Animals in New Guinea: Preying the Game in The Highlands. Routledge: Studies in Environmental Anthropology.

Sillitoe, Professor Paul; and Pointet, Dr. Abram. 2009. Was Valley Anthropological Archives. Retrieved on April 1, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.wolaland.org/page/

Strahan, Ronald; and Conder, Pamela. 2007. Dictionary of Australian and New Guinean Mammals. CSIRO Publishing.

Tate, G. H. H. 1945. "Results of the Archbold Expeditions, No. 52. The Marsupial Genus Phalanger." American Museum Novitates 1283:1-41.

Tate, G. H. H.; and Archbold, R. 1935. "Results of the Archbold Expeditions. No. 3. Twelve Apparently New Forms of Muridae Other Than Rattus from the Indo-Australian region." American Museum Novitates 803:1-9.

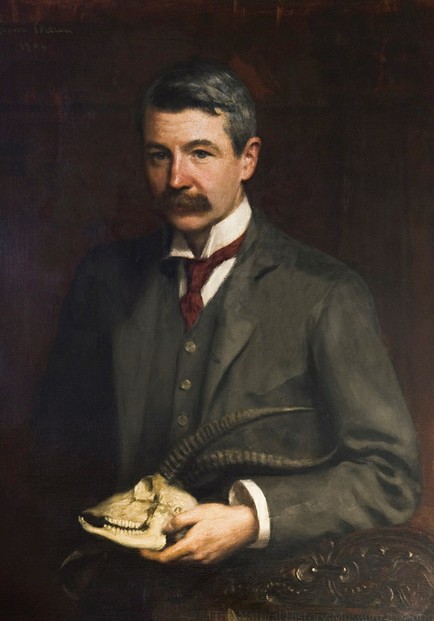

Thomas, Oldfield. 1897. "On Some New Phalangers of the Genus Pseudochirus." Annali del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Genova 18(2): 140-146. Retrieved on April 1, 2014.

- Available via Internet Archive at: http://www.archive.org/stream/annalidelmuseoci38muse#page/142/mode/1up

Thomas, Oldfield. 1897. "On the Mammals Collected in British New Guinea by Dr. Lamberto Loria." Annali del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Genova 18(2): 606-622. Retrieved on April 1, 2014.

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/7785828

- Available via Internet Archive: http://www.archive.org/stream/annalidelmuseoci38muse#page/606/mode/2up

Tyndale-Biscoe, Hugh. 2005. Life of Marsupials. Collingwood, Victoria, Australia: CSIRO Publishing.

Wilson, Don E.; and Reeder, DeeAnn M. (editors). 2005. Mammal Species

of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed), Johns Hopkins University Press.

Wrobel, Murray (Editor). 2007. Elsevier's Dictionary of Mammals: Latin English German French Italian. Oxford, U.K.: Elsevier B.V.

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Comments