Jennie Wade's birthplace: built ca. 1814 - 1820

242 - 246 Baltimore Street, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania: nikoretro, CC BY SA 2.0, via Flickr @ https://www.flickr.com/photos/bellatrix6/821104315

left to right: Georgia Wade, Mary Comfort, Mary Virginia Wade: 1861 daguerrotype by Speaits, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

J.W. Johnston, The True Story of "Jennie" Wade (1917), page 4: via Internet Archive @ https://archive.org/details/truestoryofjenn00john/page/4/mode/1up

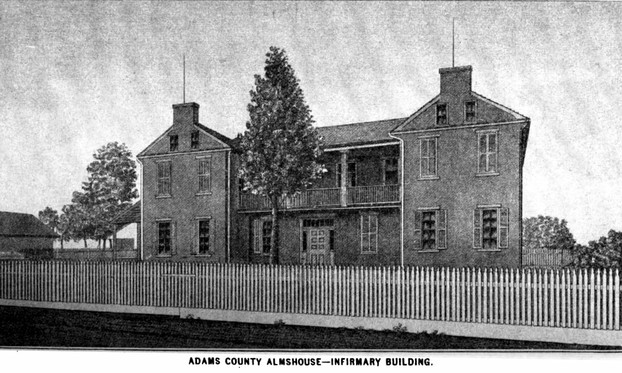

Surviving his younger daughter by nine years, James Wade passed away in the Adams County Almshouse complex

Adams County Almshouse Complex: Infirmary: via Asylum Projects @ http://www.asylumprojects.org/index.php?title=File:Adams_County_Almshouse_(2).jpg

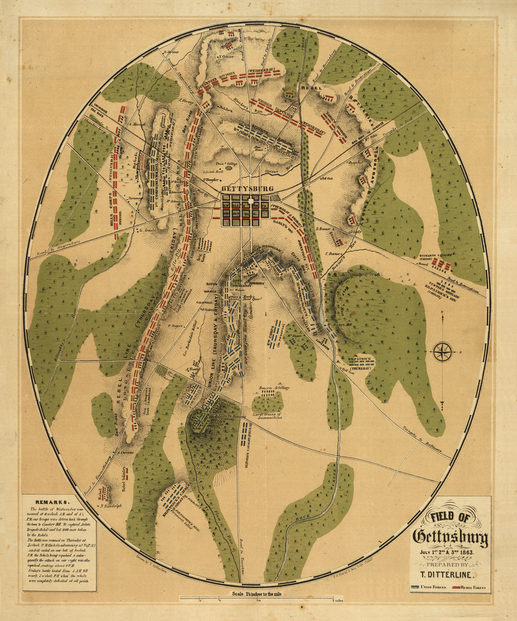

The Battle of Gettysburg: Oval-shaped map depicting troop and artillery positions, relief by hachures, drainage, roads, railroads, and houses with names of residents

Drawn by Theodore Ditterline; 1863 lithograph by P.S. Duval & Son, Philadelphia: Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FieldOfGettysburg1863.PNG

Statue of Jennie Wade in front of the house where she was fatally shot during the battle.

west side of duplex; Jennie's sister occupied northern half: Ryan Crierie (RyanCrierie), CC BY 2.0, via Flickr @ https://www.flickr.com/photos/63014123@N02/11411163106/

By battle's end, Georgia's house was pockmarked from over 100 Confederate bullets.

bullet holes from skirmishes between the Blue and the Grey: kuljuls, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr @ https://www.flickr.com/photos/dancinjul/3673326815/

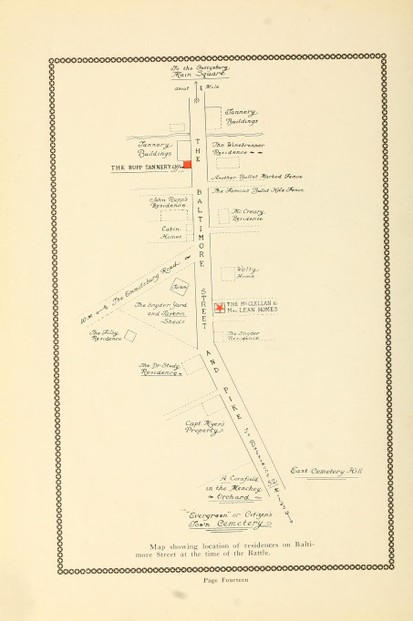

map showing location of residences on Baltimore Street at the time of the Battle

J.W. Johnston, The True Story of "Jennie" Wade (1917), page 14: , "The Library of Congress is unaware of any copyright restrictions for this item.," via Internet Archive @ https://archive.org/details/truestoryofjenni00john/page/14/mode/1up; via Internet Archive @ https://archive.org/details/truestoryofjenn00john/page/14/mode/1up

statue of Jennie holding loaf of bread and pitcher for water

Ginnie 'Jennie' Wade statue by Ivo Zini (1919-January 5, 2008) installed at Baltimore Street in 1984: Ron Cogswell, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr @ https://www.flickr.com/photos/22711505@N05/9391872823/

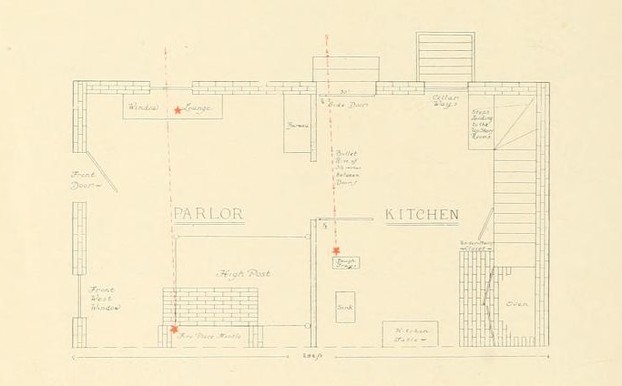

Plan of the Down Stairs Rooms of the McClellan House

J.W. Johnston, The True Story of "Jennie" Wade (1917), page 20: "The Library of Congress is unaware of any copyright restrictions for this item.," via Internet Archive @ https://archive.org/details/truestoryofjenni00john/page/20/mode/1up; via Internet Archive @ https://archive.org/details/truestoryofjenn00john/page/20/mode/1up

hole gouged by the bullet that ended Jennie's young life

closeup of right side of middle panel of outside door to kitchen: kuljuls, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr @ https://www.flickr.com/photos/dancinjul/3674136334/

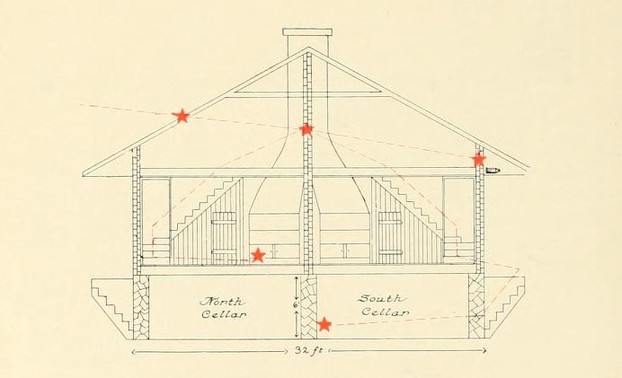

Cross Section of the McClellan House

J.W. Johnston, The True Story of "Jennie" Wade (1917), page 18: "The Library of Congress is unaware of any copyright restrictions for this item.," via Internet Archive @ https://archive.org/details/truestoryofjenni00john/page/18/mode/1up; via Internet Archive @ https://archive.org/details/truestoryofjenn00john/page/18/mode/1up

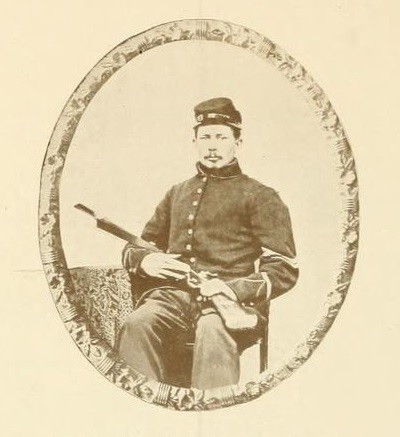

Johnston "Jack" Hastings Skelly Jr. (August 4, 1841 – July 12, 1863), Corporal, Company F, 87th Pennsylvania Infantry

J.W. Johnston, The True Story of "Jennie" Wade, a Gettysburg Maid (1917), page 32: "The Library of Congress is unaware of any copyright restrictions for this item.," via Internet Archive @ https://archive.org/details/truestoryofjenni00john/page/32/mode/1up; via Internet Archive @ https://archive.org/details/truestoryofjenn00john/page/32/mode/1up

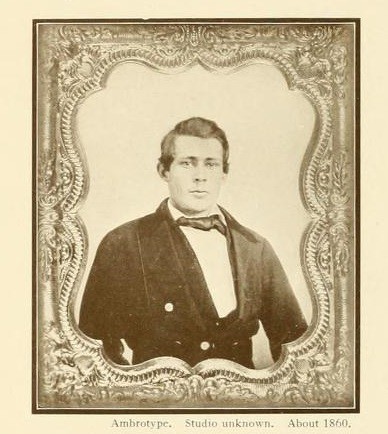

Johnston Hastings Skelly (August 4, 1841 - July 12, 1863): c. 1860 ambrotype

J.W. Johnston, The True Story of "Jennie" Wade, a Gettysburg Maid (1917), page 6: "The Library of Congress is unaware of any copyright restrictions for this item.," via Internet Archive @ https://archive.org/details/truestoryofjenni00john/page/6/mode/1up; via Internet Archive @ https://archive.org/details/truestoryofjenni00john/page/6/mode/1up

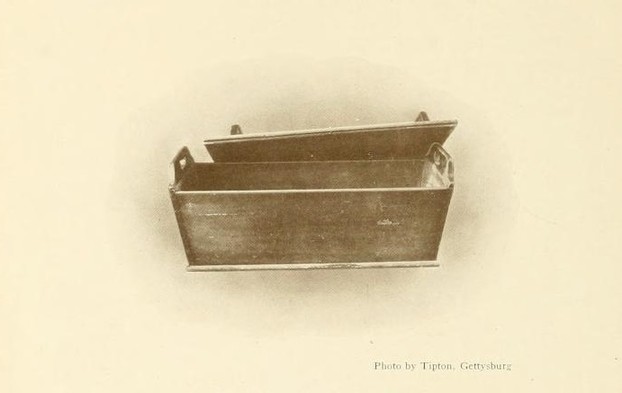

Wooden mixing tray: "This mixing tray is the one over which Miss Wade was working at the time of her death. It may be seen at the Jennie Wade House Museum."

J.W. Johnston, The True Story of "Jennie" Wade, a Gettysburg Maid (1917), page 24: "The Library of Congress is unaware of any copyright restrictions for this item.," via Internet Archive @ https://archive.org/details/truestoryofjenni00john/page/24/mode/1up; via Internet Archive @ https://archive.org/details/truestoryofjenn00john/page/24/mode/1up

A flag is allowed to fly 24 hours round-the-clock at Jennie's gravesite: this honor is accorded to only one other female-honoring site, the Betsy Ross House in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

statue by Gettysburg resident Anna M. Miller; funded by Iowa Women's Relief Corps (WRC); dedicated Sep. 16, 1901: Ryan Crierie (RyanCrierie), CC BY 2.0, via Flickr @ https://www.flickr.com/photos/63014123@N02/11411159116/

blueeyes52988. "Mary Virginia 'Jennie' Wade." YouTube, June 28, 2010, @ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sie90Tjfrg8

Jennie Wade House, Gettysburg

image taken about four decades after Jennie's death

c. 1903 dry plate glass negative by Detroit Publishing Company; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division: No known restrictions on publication, via Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Online Catalog (PPOC) @ https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2016803313/

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Comments