Bassarova, M.; Archer, M.; and Hand, S.J. December 20, 2001. “New Oligo-Miocene Pseudocheirids (Marsupialia) of the Genus Paljara from Riversleigh, Northwestern Queensland.”Memoirs of the Association of Australasian Palaeontologists 25:61-75.

Collett, Robert. 1884. "On some apparently new Marsupials from Queensland." Proceedings of the Scientific Meetings of the Zoological Society of London for the Year 1884, Vol. 52, Issue 3 (May 20, 1884): 381-389. London: Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer. Retrieved on March 12, 2014.

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/28690276

- Available via Internet Archive at: https://archive.org/stream/proceedingsofgen97scie#page/317/mode/1up

Dennis, Linda. "Greater Glider: Petauroides volans." Fourth Crossing Wildlife. Retrieved on March 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.fourthcrossingwildlife.com/GreaterGlider.htm

Department of Environment and Heritage Protection. 2014. . WetlandInfo. Brisbane: The State of Queensland Government Wetlands Program. Retrieved on March 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://wetlandinfo.ehp.qld.gov.au/wetlands/ecology/components/species/?petauroides-volans

Duff, Andrew; and Lawson, Ann. 2004. Mammals of the World: A Checklist. Yale University Press.

Flannery, Timothy F. 1994. Possums of the World: A Monograph of the Phalangeroidea. Chastwood, Australia: GEO Productions in association with the Australian Museum.

Foley, W.J.; Kehl, J.C.; Nagy, K.A.; Kaplan, I.R.; and Borsboom, A.C. 1990. "Energy and Water Metabolism in Free-Living Greater Gliders, Petauroides-Volans." Australian Journal of Zoology 38(1):1–9. Retrieved on March 14, 2014.

- Available via CSIRO Publishing at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/ZO9900001

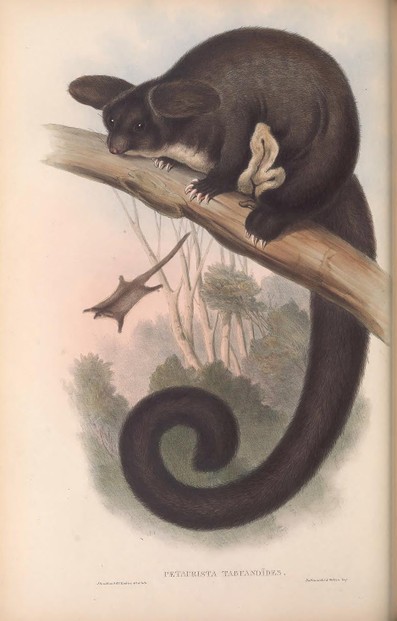

Gould, John. 1863. Mammals of Australia. Volume I. London: John Gould.

"Greater Glider." redOrbit: Reference Library. Retrieved on March 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.redorbit.com/education/reference_library/animal_kingdom/mammalia/2579712/greater_glider/

"Greater Glider: Petauroides volans." Pp. 119-120 in Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia, Second Edition. Volume 13: Mammals II, edited by Michael Hutchins, Devra G. Kleiman, Valerius Geist, and Melissa C. McDade. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group, Inc., division of Thomson Learning Inc., 2004.

"Greater Glider (Petauroides volans)." OzAnimals Australian Wildlife: Mammals. Retrieved on March 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.ozanimals.com/Mammal/Greater-Glider/Petauroides/volans.html

"Greater Glider (Petauroides volans)." Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland. Retrieved on March 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.wildlife.org.au/wildlife/speciesprofile/mammals/gliders/greater_glider.html

Hume, Ian D. 1999. Marsupial Nutrition. Melbourne, Australia: Cambridge University Press.

Kerle, Jean Anne. 2001. Possums: The Brushtails, Ringtails and Greater Glider. Sydney: University of New South Wales Australian Natural History Series. Retrieved on March 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://books.google.com/books?id=YDM0hjAwchUC&lpg=PT65&dq=Petropseudes%20dahli&pg=PT66#v=onepage&q=Petropseudes%20dahli&f=false

Lunney, D.; Menkhorst, P.; Winter, J.; Ellis, M.; Strahan, R.; Oakwood, M.; Burnett, S.; Denny, M.; and Martin, R. 2008. "Petauroides volans." In: IUCN 2008. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Red List of Threatened Species.Retrieved on March 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/40579/0

Maloney, Kevin S. 2007. The Status of the Greater Glider "Petauroides volans" in the Illawarra Region. University of Wollongong Research Online: School of Biological Sciences MSc-Res Thesis. Retrieved on March 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/59/

Men at Work. 1981. Business as Usual. NY: CBS.

Menkhorst, Peter; and Knight, Frank. 2001. A Field Guide to the Mammals of Australia. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Meredith, Robert W.; Mendoza, Miguel A.; Roberts, Karen K.; Westerman, Michael; and Springer, Mark S. March 2, 2010. “A Phylogeny and Timescale for the Evolution of Pseudocheiridae (Marsupialia: Diprotodontia) in Australia and New Guinea.” Journal of Mammalian Evolution17(2):75-99. Retrieved on March 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2987229/

Myers, P.; Espinosa, R.; Parr, C.S.; Jones, T.; Hammond, G.S.; and Dewey, T.A.. 2014. "Petauroides volans: Greater Glider (On-line)." The Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved on March 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Petauroides_volans/pictures/collections/contributors/Grzimek_mammals/Pseudocheiridae/Petauroides_volans/

Nagel, Juliet. "Petauroides volans: Greater Glider (On-line)." Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved on March 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Petauroides_volans/

Nowak, Ronald M. 1999. Walker's Mammals of the World, Sixth Edition. Volume I. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Nowak, Ronald M. 2005. Walker's Marsupials of the World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

"Petauroides volans: Greater Glider." Digital Morphology: A National Science Foundation Digital Library at University of Texas, Austin. Retrieved on April 4, 2014.

- Available at: http://digimorph.org/specimens/Petauroides_volans/

"Petauroides volans: Greater Glider." Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved on March 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://eol.org/pages/323829/details

"Petauroides volans (Kerr, 1792): Greater Glider." The Atlas of Living Australia: Australia's Species. Retrieved on March 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://bie.ala.org.au/species/PETAUROIDES+VOLANS

"Petauroides volans (Kerr, 1792): Greater Glider." Species 2000 & ITIS Catalogue of Life: 2011 Annual Checklist. Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved on March 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=609821

Pope, Matthew. 2002. A Study of the Greater Glider (Petauroides Volans) Persisting in Remnant Eucalypt Patches, Surrounded by a Softwood Plantation Matrix. Australian National University.

Ride, W.D.L. A Guide to the Native Mammals of Australia. Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1970.

Strahan, Ronald; and Conder, Pamela. 2007. Dictionary of Australian and New Guinean Mammals. CSIRO Publishing.

Ulyatt, Susanne (webmaster). "About the Greater glider (Petauroides volans)." Wildlife Mountain: The Animals. Retrieved on March 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.wildlifemountain.com/Greaterglider.htm

"Wet Tropics of Queensland." UNESCO World Heritage Centre List. Retrieved on March 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/486

Wilson, D.E.; and Reeder, D.M. 2005. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, Third Edition. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Comments