Baskin, Leonard. 2003. "Musk Deer (Moschinae)." Pp. 335-338 in Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopeda, 2nd edition. Volume 15, Mammals IV, edited by Michael Hutchins, Devra G. Kleiman, Valerius Geist, and Melissa C. McDade. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group.

Bisby, F.A.; Roskov, Y.R.; Orrell, T.M.; Nicolson, D.; Paglinawan, L.E.; Bailly, N.; Kirk, P.M.; Bourgoin, T.; Baillargeon, G.; and Ouvrard, D. (red.). 2011. "Moschus leucogaster Hodgson, 1839." Species 2000 & ITIS Catalogue of Life: 2011 Annual Checklist. Reading, UK. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.catalogueoflife.org/col/details/species/id/19742795

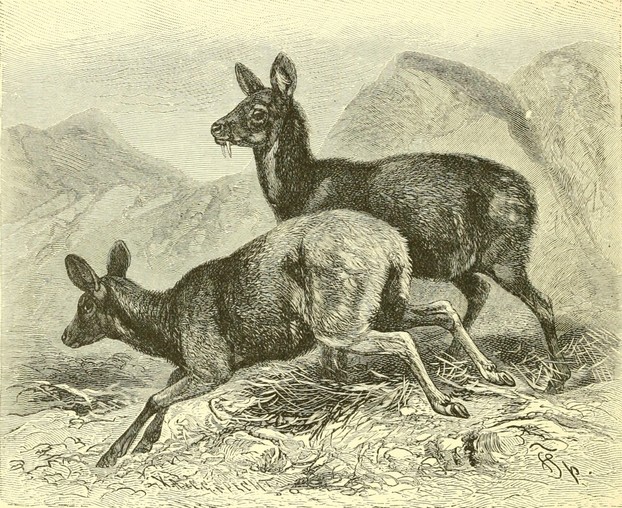

Cuvier, Fréderic. 1816 - 1829. Dictionnaire des sciences naturelles: Planches. 2e partie: règne organisé. Zoologie, Mammiféres. Paris: F.G. Levrault.

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/24392850

Das, Sarat Chandra. 1902. A Journey to Lhasa and Central Tibet. Second edition, revised. New York: E.P. Dutton & Company; London: John Murray.

- Available via Internet Archive at: https://archive.org/details/journeytolhasace00dass

Edwards, R. 2010. "Himalayan Musk Deer (Moschus leucogaster)." ARKive.org. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.arkive.org/himalayan-musk-deer/moschus-leucogaster/

Edwards, Sydenham. 1817. Botanical Register: Consisting of Coloured Figures of Exotic Plants, Cultivated in British Gardens; With Their History and Mode of Treatment. Volume III. London: James Ridgway.

- Available via Internet Archive at: https://archive.org/stream/mobot31753002748157

Environment and Development Desk, DIIR, CTA. 21 January 2014. “Musk Deer.” Tibet Nature Environmental Conservation Network. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.tibetnature.net/en/musk-deer/

Flerov, Konstantin Konstantinovich. 1952. Musk Deer and Deer. Moscow, Russia: Academy of Sciences of the USSR.

Geptner, V. G. (Vladimir Georgievich), N.P. Naumov, P.B. Yurgenson, A.A. Sludskii, A.F. Chirkova, and A.G. (Andrei Grigorvich) Bannikov. 2001. Mammals of the Soviet Union. Volume II, Part 1b: Carnivora (Weasels, Additional Species). Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Libraries and The National Science Foundation.

- Available via Internet Archive at: https://archive.org/details/mammalsofsov212001gept

Green, M.J.B. 1987. "Some Ecological Aspects of a Himalayan Population of Musk Deer." Pp. 307-319 in The Biology and Management of Cervidae, edited by C.M. Wemmer. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Groves, C.P. 2011. "Family Moschidae (Musk-Deer)." In Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Volume 2: Hooved Mammals edited by D.E. Wilson and R.A. Mittermeier. Barcelona, Spain: Lynx Edicions.

Groves, C.P.; and Grubb, P. 1987. "Relationships of Living Deer." Pp. 1-40 in Biology and Management of the Cervidae edited by C. Wemmer. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Groves, C. P.; Yingxiang, W.; and Grubb, P. 1995. "Taxonomy of Musk-Deer, Genus Moschus (Moschidae, Mammalia)." Acta Theriologica Sinica 15(3):181-197.

Grubb, P. 2005. "Artiodactyla." Pp. 637-722 in Mammal Species of the World. A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd Edition) Edited by D.E. Wilson and D.M. Reeder. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Grubb, P. 1990. "List of Deer Species and Subspecies." Deer, Journal of the British Deer Society 8:153-155.

Hodgson, B.H. 1844. "Classified Catalogue of Mammals of Nepal." Calcutta Journal of Natural History 4:284-294.

Hodgson, B.H. 1842. "Notice of the Mammals of Tibet, with Descriptions and Plates of Some New

Species." Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 11:275-289.

- Available via Internet Archive at: https://archive.org/details/journalasiatics38benggoog

Jardine, Sir William. 1855 (?). The Naturalist's Library. Vol. XXI: Mammalia: Deer, Antelopes, Camels, etc. London: Henry G. Bohn.

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/18735738

Lydekker, R. (Richard). 1900. The Great and Small Game of India, Burma, & Tibet. London: Rowland Ward, Limited.

- Available via Internet Archive at: https://archive.org/details/greatsmallgameof1900lyde

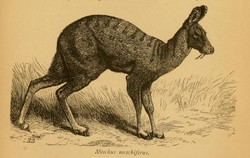

Lydekker, Richard. 1894. The Royal Natural History. Volume II section IV. London and New York: Frederick Warne & Co.

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/28360369

Meng, X.; Zhou, C.; Hu, J.; Li, C.; Meng, Z.; Feng, J.; and Zhou, Y. 2006. "Musk Deer Farming in China." Animal Science 82:1-6.

"Moschus leucogaster (Himalaya Musk Deer)." Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- Available at: http://eol.org/pages/7240240/details

"Moschus chrysogaster leucogaster." uBio: Universal Biological Indexer and Organizer NamebankID 6511275. Woods Hole, MA: The Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.ubio.org/browser/details.php?namebankID=6511275

"Moschus leucogaster (Himalayan Muskdeer)." ZipcodeZoo: Species Identifier 2514177. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- Available at: http://zipcodezoo.com/Animals/M/Moschus_leucogaster/

“Moschus leucogaster Hodgson, 1839.” ITIS Report: Taxonomic Serial No. 898197. Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=898197

Myers, P.; Espinosa, R.; Parr, C.S.; Jones, T.; Hammond, G.S.; and Dewey, T.A. 2014. "Moschus leucogaster (Himalayan Musk Deer)." The Animal Diversity Web (Online). University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- Available at: http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Moschus_leucogaster/classification/

Nowak, R.M. 1999. Walker’s Mammals of the World. Sixth edition. Baltimore, MD; and London, England: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Pickrell, John. 7 September 2004. “Poachers Target Musk Deer for Perfumes, Medicines.” National Geographic.com: News. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- Available at: http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2004/09/0907_040907_muskdeer.html

Plummer, Jaclyn. 2011. "Moschus leucogaster: Himalayan Musk Deer (Online)." The Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- Available at: http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Moschus_leucogaster/

Rue, Dr. Leonard Lee III. 2003. The Encyclopedia of Deer: Your Guide to the World's Deer Species, Including Whitetails, Mule Deer, Caribou, Elk, Moose, and More. Stillwater MN: Voyageur Press.

Smith, A.; and Xie, Y. 2008. The Mammals of China. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Su, B.; Wang, Y.X.; Lan, H.; Wang W.; and Zhang, Y. P. 2001. "Phylogenetic Study of Complete Cytochrome b Genes in Musk Deer (Genus Moschus) Using Museum Samples." Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 12(3):241-249.

Timmins, R.J.; and Duckworth, J.W. 2008. "Moschus leucogaster." IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/full/13901/0

Yang, Q. S.; Meng, X.X.; Xia, L.; and Lin Feng, Z.J. 2003. "Conservation Status and Causes of Decline of Musk Deer (Moschus spp.) in China." Biological Conservation 109:333-342.

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Comments