Baker, Paul E., and Helen Baker. Kākāwahie (Paroreomyza flammea) and O`ahu `Alauahio (Paroreomyza maculata). In: Alan F. Poole and Frank Gill, eds. The Birds of North America, No. 503. Philadelphia: The Birds of North America, Inc., 2000.

Banko, Winston E. History of Endemic Hawaiian Birds Specimens in Museum Collections. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i, 1979.

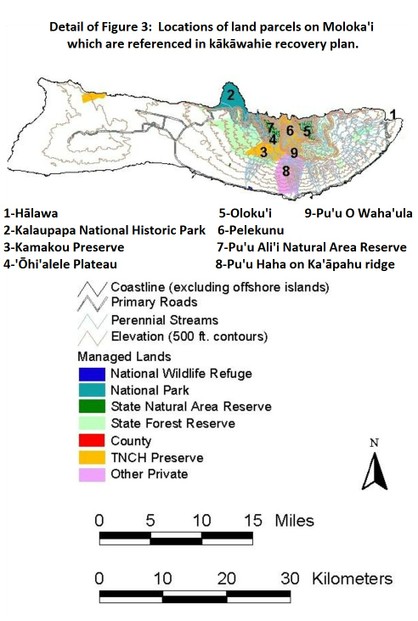

“Forest Birds: Kākāwahie or Moloka’i Creeper, Paroreomyza flammea.” Hawai’i’s Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy, October 1, 2005. Honolulu: Hawai’i Department of Land and Natural Resources, 2005.

Hawaiian High Islands Ecoregional Planning Team. An Ecoregional Assessment of Biodiversity Conservation for the Hawaiian High Islands. The Nature Conservancy of Hawai’i, 2006.

Ives-Boynton, Sheryl. Hawaii A-B-C Coloring Book. Honolulu: Ka’imi Pono Press, 1995.

“Kalaupapa Settlement Boundary Study Along North Shore to Halawa Valley, Molokai.” National Park Service: Pacific West Region, Honolulu. 2000.

- Available at: http://www.botany.hawaii.edu/basch/uhnpscesu/htms/MinkStdy/nscliffC.htm

“Moloka’i Creeper (Paroreomyza flammea) Hawaiian name, Kaka-wahie.” Hawai’i Forests & Wildlife Teacher Resources. Honolulu: Hawai’i Department of Land and Natural Resources, Division of Forestry and Wildlife. Updated 8/30/02.

- Available at: http://www.state.hi.us/dlnr/dofaw/kids/teach/MolCreep.pdf

"Moloka'i Forest Reserve." Hawai'i Forest Reserve System. Hawai'i Department of Land and Natural Resources.

- Available at: http://hawaii.gov/dlnr/dofaw/forestry/FRS/reserves/mauinuifr/molokai-forestreserve

Munro, George C. Birds of Hawaii. 2nd Edition. Rutland VT and Tokyo Japan: Charles E. Tuttle Co., Inc. 1964.

National Park Service. Kalaupapa Settlement Boundary Study Along North Shore to Halawa Valley, Molokai. Site Investigation Report by Bryan Harry and Gary Barbano. Last updated October 24, 2001.

- Available at: http://www.nps.gov/pwro/piso/minkstdy/nscliffC.htm#summary

"Oloku'i." Hawai'i Natural Area Reserves System. Hawai'i Department of Land and Natural Resources.

- Available at: http://hawaii.gov/dlnr/dofaw/nars/reserves/molokai/olokui

Pekelo, Noah, Jr. “Nature notes from Molokai.” ‘Elepaio 24 (1963): 17-18.

“Place Names of Hawai’i.” Ulukau, the Hawaiian Electronic Library. University of Hawai’I Press.

"Pu'u Ali'i." Hawai'i Natural Area Reserves System. Hawai'i Department of Land and Natural Resources.

- Available at: http://hawaii.gov/dlnr/dofaw/nars/reserves/molokai/puualii

Reynolds, Michelle H., and Thomas J. Snetsinger. “The Hawai’i Rare Bird Search 1994-1996.” Studies in Avian Biology 22 (2001): 133-143.

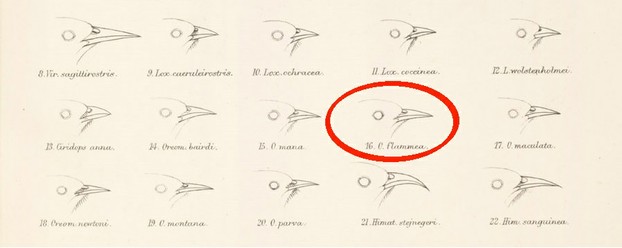

Rothschild, Lionel Walter. The Avifauna of Laysan and the Neighbouring Islands with a Complete History to Date of the Birds of the Hawaiian Possession. Illustrated with Coloured and Black Plates by Messrs Keulemans and Frohawk; and Plates from Photographs, Showing Bird-Life and Scenery. Four volumes. London: R.H. Porter, 1893-1900.

- Available at: http://www.sil.si.edu/digitalcollections/nhrarebooks/rothschild/CF/index.cfm

Scott, J.Michael, Stephen Mountainspring, Fred L. Ramsey, and Cameron B. Kepler. Forest bird communities of the Hawaiian Islands: their dynamics, ecology, and conservation. Studies in Avian Biology No. 9. Waco, Texas: Cooper Ornithological Society, 1986.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Draft Revised Recovery Plan for Hawaiian Forest Birds. Portland: Region 1 US Fish and Wildlife Service, August 2003. (428 pages)

- Available at: http://www.fws.gov/pacific/ecoservices/endangered/recovery/documents/HawaiiForestBirdsDraftRevisedRecoveryPlan.pdf

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Maui-Molokai Forest Birds Recovery Plan. Portland: Region 1, 1984. (110 pages)

- Available via HathiTrust at: http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/002518102

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Revised Recovery Plan for Hawaiian Forest Birds. Portland: Region 1, 2006. [622 pages]

- Available at: http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/recovery_plan/060922a.pdf

Wagner, W. L., D. R. Herbst, and S. H. Sohmer. Manual of flowering plants of Hawai'i. Bishop Musuem and University of Hawai'i Press, Honolulu, 1990.

Wilson, Scott Barchard, and Arthur Humble Evans. Aves Hawaiiensis: The Birds of the Sandwich Islands. London: R.H. Porter, 1890-1899.

Yoshinaga, Alvin Y. "A naturalist's visit to Moloka'i in 1896." 'Elepaio, Volume 57, No. 1 (1997): 76-79. Translation and annotation of: H.H. Schauinsland, Hugo Hermann, "Ein Besuch auf Moloka'i, der Insel der Aussatzigen." Abhandlungen naturwissenschaflicher Vereine zu Bremen, Volume 16 (1906): 513-543.

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Comments

EliasZanetti, Yes, reckless, as in joyriding to create roadkill (even though nature has a right to go out for a bite to eat at night) or as in taking too many specimens for collections or as in fluffing up clothing or hats with feathers. What if every single species has a role to play, and some day we just might realize what it was?

Thank you for visiting and commenting.

Good, well researched article. Unfortunately, human activity (especially the reckless one) drives more and more species closer to extinction.