Bakthir, H., N.A. Awadh Ali, N. Arnold, A. Teichert, L. Wessjohann. (2011) “Anticholinesterase activity of endemic plant extracts from Soqotra.” African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicines, Volume 8, Number 3 (2011).

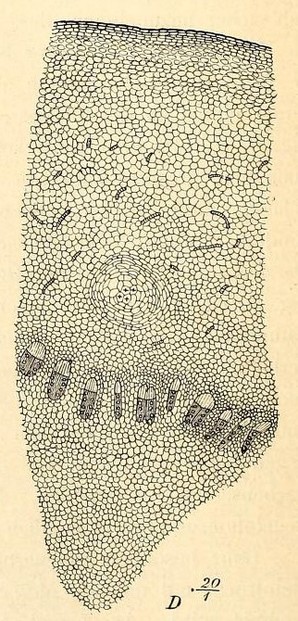

Balfour, Isaac Bayley. Botany of Socotra. Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Vol. XXXI. Edinburgh: Robert Grant & Son; London: Williams & Norgate, MDCCCLXXXVIII (1888).

- Available via Internet Archive at: http://archive.org/details/transactionsofro311888roy

Balfour, Isaac Bayley. Botany of Socotra. Forming Vol. XXXI of The Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Edinburgh: Robert Grant & Son; London: Williams & Norgate, MDCCCLXXXVIII (1888).

- Available at Biodiversity Heritage Library at: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/42457.

- Available at Internet Archive at: http://archive.org/ details/botanyofsocotra00balf.

Brown, Gary, and Bruno A. Mies. Vegetation Ecology of Socotra. Series: Plant and Vegetation, Vol. 7. Dordrecht, Heidelberg, New York, London: Springer, 2012.

"Diagnoses plantarum novarum Phanerogamarum Socotrensium, etc.; quas elaboravit Bayley Balfour, Scientiae Doctor et in Universitate Glascuensi rerum botanicarum regius professor. Pars Teria," Proceedings of The Royal Society of Edinburgh, Volume XII (November 1882 to July 1884): 76-98.

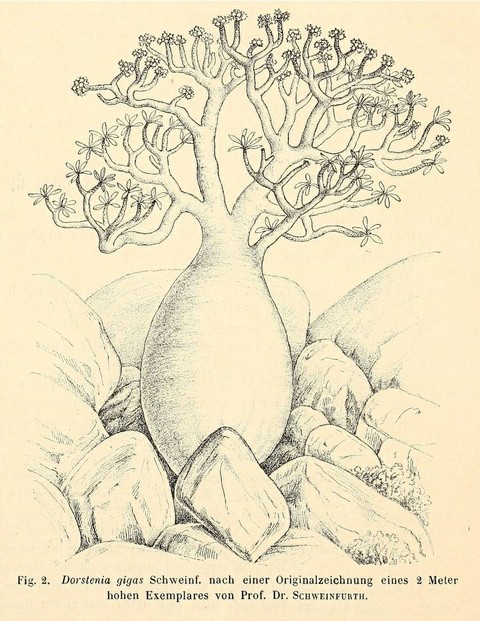

Engler, A. (Adolf). Monographieen afrikanischer Pflanzen-Familien und - Gattungen. I. Moraceae (Excl. Ficus). Mit Tafel I-XVIII und 4 Figuren im Text. Leipzig: Wilhelm Engelmann, 1898.

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/ 113570

- Available via Internet Archive at: http://archive.org/details/monographieenafr01engl

Engler, A. (Adolf), and O. (Oscar) Drude. Die Vegetation der Erde: Sammlung pflanzengeographischer Monographien. IX: Die Pflanzenwelt Afrikas, insbesondere seiner tropischen Gebiete. Grundzü ge der Pflanzenverbreitung in Afrika und die Charakter-pflanzen Afrikas von A. Engler. III Band, I Heft. Leipzig: Wilhelm Engelmann, 1915.

- Available via Internet Archive at: http://archive.org/details/mobot31753002290093

Forbes, Henry O., ed. The Natural History of Sokotra and Abd-el-Kuri: Being the Report upon the Results of the Conjoint Expedition to these Islands in 1898-9, by Mr. W.R. Ogilvie-Grant, of the British Museum, and Dr. H.O. Forbes, of the Liverpool Museums, together with information from other available sources Forming A Monograph of the Islands. Liverpool-London: The Free Public Museums, 1903.

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: http://biodiversitylibrary.org/item/80063

- Available via Internet Archive at: http://archive.org/details/naturalhistoryof00forb

Franke, K., A. Porzel, M. Massaoud, G. Adam and J. Schmidt. "Furanocoumarins from Dorstenia gigas." Phytochemistry, Volume 56 Number 6 (March 2001): 611-621.

Harris, W. Victor. "Termites from Socotra (Isoptera)." Journal of Natural History (series 12), Vol. 7, Issue 79 (1954): 493-496.

Helmolt, H.F. (Hans Ferdinand), ed. The History of the World: A Survey of Man's Record. Complete in Eight Volumes. Volume III: West Asia and Africa. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1903.

- Available via Internet Archive at: http://archive.org/details/cu31924088477959

Kislev, Mordechai E., Anat Hartmann and Ofer Bar-Yosef. (2006) “Early domesticated fig in Jordan Valley.” Science, 312 (5778): 1372-1374. DOI: 10.1126/science.1125910

- Available at: http://www.sciencemag.org/content/312/5778/1372.short

Krogstrup, P., J.I. Find, D.J. Gurskov and M.M.H. Kristensen. "Micropropagation of Socotran fig, Dorstenia gigas Schweinf. Ex Balf. f. – a threatened species, endemic to the island of Socotra. Yemen." In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology. Plant, Vol. 41, No. 1 (Jan. – Feb., 2005): 81-86.

- Available via JSTOR at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4293821

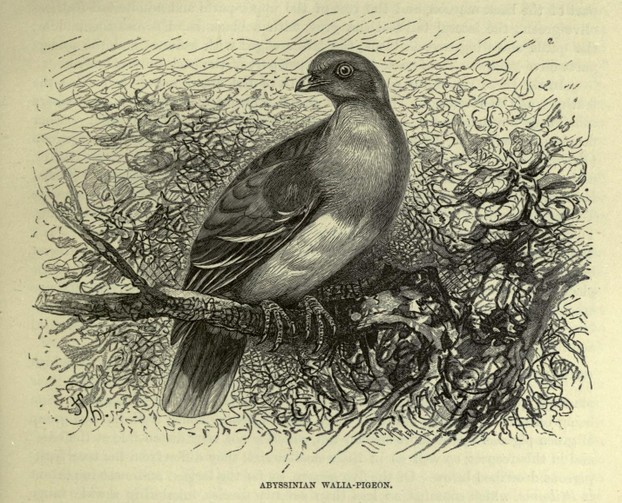

Lydekker, Richard, ed. The Royal Natural History. Volume IV: Birds. London and New York: Frederick Warne and Co., 1895.

- Available via Internet Archive at: http://archive.org/details/royalnaturalhist04lyderich

Miller, Anthony G. (2004). "Dorstenia gigas." In: IUCN 2011. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.1.

- Available at: http://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/30399/0 (Last accessed October 28, 2011)

Miller, Anthony G. and Thomas A. Cope. Flora of the Arabian Peninsula and Socotra. Volume 1. Edinburgh University Press, 1996.

Norris, Scott. “Ancient Fig Find May Push Back Birth of Agriculture.” National Geographic News, June 1, 2006.

- Available at: http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2006/06/060601-agriculture.html

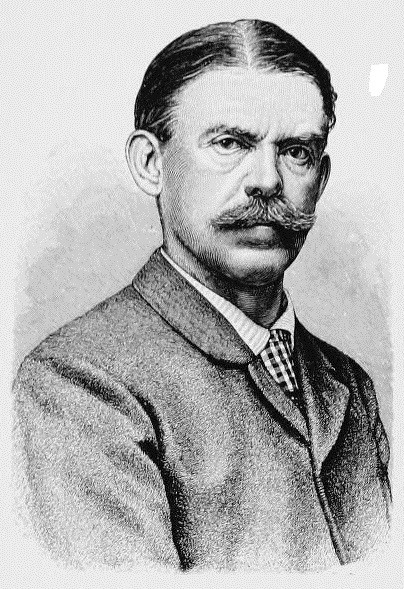

"Postcard from Georg Schweinfurth to Sir William Thiselton-Dyer; from Cairo; 10 March 1883." Two page postcard comprising two images; folio 431.

"Postcard from Georg Schweinfurth to Sir William Thiselton-Dyer; from Cairo; 10 March 1883; two page postcard comprising two images; folio 431

"Postcard from Georg Schweinfurth to Sir William Thiselton-Dyer; from Cairo; 10 March 1883." Two page postcard comprising two images; folio 431. Global Plants: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: Archives: Directors' Correspondence. plants.jstor.org. Ithaka Harbors, Inc.

- Available via JSTOR at: plants.jstor.org/visual/kadc0664

Song, Jr., Leo C. "Dorstenia gigas, a succulent fig from Socotra Island." Stories Out of School. California State University-Fullerton Department of Biological Science, July 14, 1999.

- Available at: http://biology.fullerton.edu/facilities/greenhouse/stories_out_of_school/dorsteniagigas.html

Wranik, Wolfgang. Fauna of the Socotra Archipelago: Field Guide. With contributions by Omar S. Al-Saghier, Simon Aspinall, Richard F. Porter, and Herbert Rösler. Rostock, Germany: Universität Rostock, 2003.

Wranik, Wolfgang. "Mantodea / Dermaptera / Blattodea / Isoptera / Embioptera." Socotra: Texts/Pictures. www.biologie.uni-rostock.de. Universität Rostock Institut für Biowissenschaften (University of Rostock Institute of Biological Sciences).

- Available at: http://www.biologie.uni-rostock.de/wranik/socotra/texts/19.htm

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Comments

There must be farmer and villager traditional cookbooks and recipe boxes.

Wouldn't it be wonderfully wondrous to wend one's way through how farmers and villagers from time immemorial work Socotran figs into their daily and festival-day diets?

The queen of Sheba came from an area configured within what categorizes as Yemen land nowadays.

Yemen is a hop, a jump and a skip -- ;-D -- in the Sinai peninsula up from the island Socotra.

So that biogeography makes me mull whether the afore-mentioned queen mixed some Socotra marvels within everything that she moved into Israelite King Solomon's throne room.

Mightn't one such marvel be Socotran fig trees and their figs?

The computer crashed again before I could convey another component of fig drinkability and potability.

Fig species do well with their fruits jam-ified and jelly-ified.

So isn't it interesting to imagine a fig-species garden from which fig fruits invite ingesting comparatively to invoke which is most inclusive of appearance, fragrance, taste and texture?

The computer crashed before I could communicate another component of fig drinkability and potability.

Its fruit perhaps draws most those who delight in fig species.

Some species additionally lodge such luscious parts as leaves that link to boiled, grilled, steamed spinach substitutes; cocktail or tea syrups; and cooked-fish, meat, rice wraps.

Mightn't fig fruits and seeds mix munchingly with fig-leaf salads?

Province- or state-, national-, international-model gardens appeal to me.

The island Socotra emerges eminently among the afore-elaborated projects because of ancient, unusual wildlife.

The Socotran fig tree (Dorstenia gigas) interests me because of its edible fruit.

Mightn't a sub-garden within a world garden quite movingly muster all the Dorstenia-genus species to match how their figs measure against one another as to most attractive, fragrant, tasty munchable?

jptanabe, Yes, strangeness is definitely a characteristic of plant life on the remote archipelago of Socotra. The fig tree is pretty amazing in what it can tolerate. For example, Socotra's better known "cousin" has been known to grow in micro climates in places where it wouldn't ordinarily grow. So perhaps you have a micro climate? If not, it just may work if you have the equipment of a conservatory, greenhouse or sunroom.

Thank you for visiting and commenting.

Goodness, that's one strange looking tree! I wish I could have one, but I'm sure it wouldn't like it where I live.