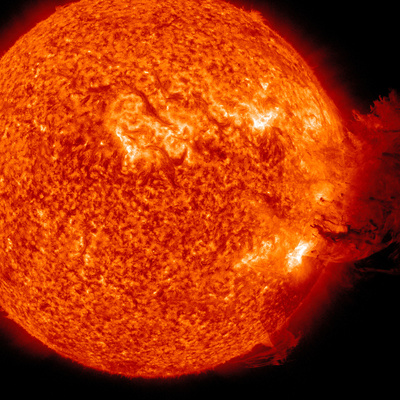

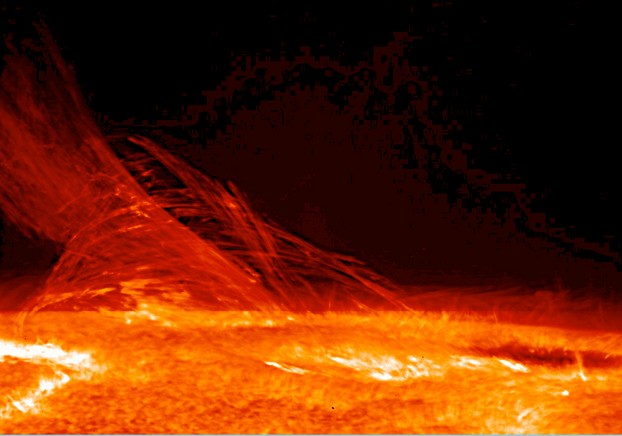

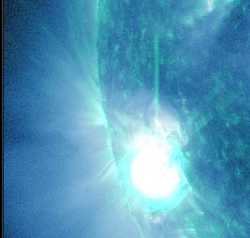

The October 22 X-flare did not launch a massive solar booger at us, ahem, a Coronal Mass Ejection, which is the usual cause of voltage spikes on the ground. Earth's ozone layer probably got a good workout absorbing X-rays, gamma rays, and all that yummy solar radiation.

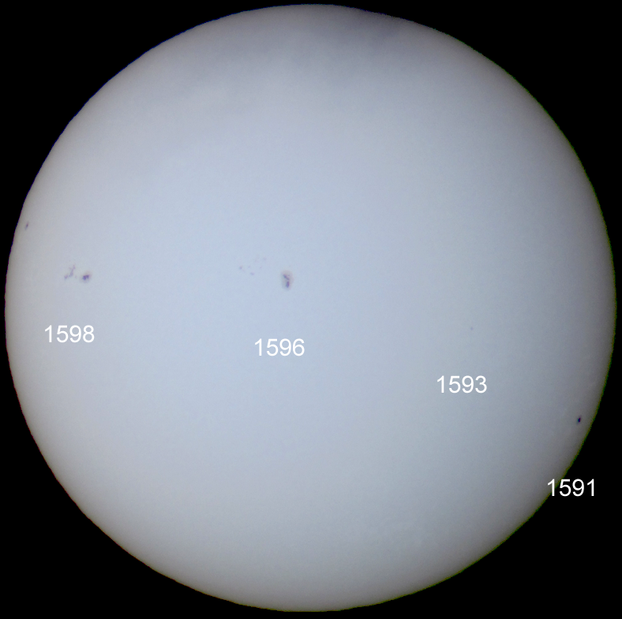

Still, I'm intrigued about the timing. The NASA video above shows the solar flare peaked at 11:17 EST. TechCrunch's article covering the AWS server problems and outages at Reddit, Pinterest, Foursquare and elsewhere show the trouble started around 1:38 EST and got worse over the next few hours, while CBS reported that the disruption started around 2:03 EST. Did the sunspot continue to pump out enough jolts across the electromagnetic spectrum to cause some of that, or is it all just a coincidence? It's tempting to see a connection.

Nevertheless, after sifting through science articles on solar flare impacts and tossing out all the doomsday conspiracy theory websites that believe that the Mayans could predict armageddon when they couldn't even predict their own civilization's demise (actually, they didn't predict armageddon, just a calendar reset, but that's another topic) — anyway, I suspect that glitches and outages for Amazon, Reddit, Pinterest and Squidoo on October 22 were due to good, old-fashioned, terrestrial gremlins. Apologies for the headline.

The thing I find frustrating is that it's annoyingly difficult to find out just what the chances are that a big data server could be damaged or disrupted by electromagnetic pulses from solar flares. This is partly because most of our internet technology is young enough that we simply don't have years of data to draw upon, and partly because most of what's known is classified or hidden by companies trying to maintain industry secrets.

According to the science article I linked to above, small electronics and computers are liable to experience temporary glitches at most that can be solved with a reboot. Computers have a certain amount of shielding to protect them from voltage fluctuations, nearby lightning strikes, drunken college students sticking magnets on them, that sort of thing.

But what about big huge data centers with masses of computers hooked together that would dwarf even my college's 1989 VAX mainframe? They've got shielding, of course, but like power grid stations, they're a lot bigger, with more parts to fry. At least they aren't sending out massive power lines across hundreds of miles of open space acting as a ginormous spiderweb to catch whatever the sun throws at us.

Still, I'm not sure Google's data center stormtrooper provides sufficient protection against an 1859 Carrington Flare sized event. And once again, even if the servers are not damaged by solar flares, if power goes out for a large region, the web goes out, too. Then again, no Reddit is the least of our woes when, as this NASA study points out, the fridge and toilet aren't working.

Space Shuttle Endeavour at California Science Centeron 10/27/2012

Space Shuttle Endeavour at California Science Centeron 10/27/2012

How The Shift to Mobile Impacts Online Writers' Bottom Lineon 10/21/2012

How The Shift to Mobile Impacts Online Writers' Bottom Lineon 10/21/2012

Amazing Videos: Stuff Launched into (Near) Space with Weather Balloonson 10/16/2012

Amazing Videos: Stuff Launched into (Near) Space with Weather Balloonson 10/16/2012

Space Shuttle Endeavour From Up Close: My Photoson 10/14/2012

Space Shuttle Endeavour From Up Close: My Photoson 10/14/2012

Comments