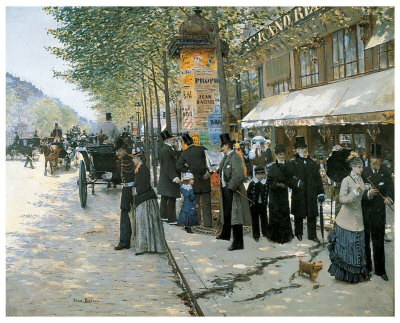

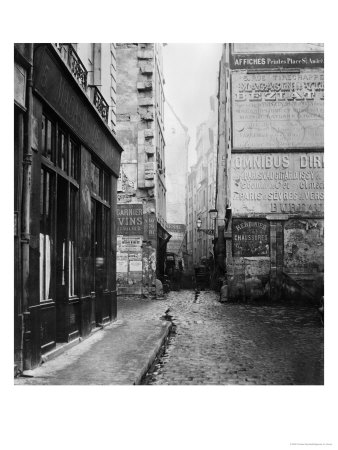

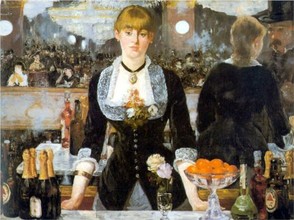

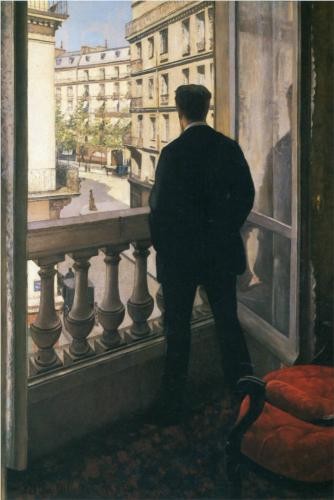

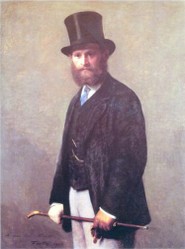

But what was so special about the flâneur that attracted not only poets, but novelists and painters too? A man walking along the street surveying the crowd, always alone, stopping to stroll into an arcade and gaze at the merchandise on show, pausing to observe the hurrying crowds, set apart from them by his sauntering pace, his dandyism...what is so significant?

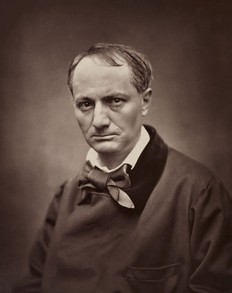

In The Painter of Modern Life Baudelaire described this new man of the street:

"The crowd is his element, as the air is that of birds and water of fishes. His passion and his profession are to become one flesh with the crowd. For the perfect 'flaneur', for the passionate spectator, it is an immense joy to set up house in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement, in the midst of the fugitive and the infinite."

He continues in this vein, describing a kind of physical and psychological freedom that was rarely if ever experienced by the women of a great metropolis.

'To be away from home and yet to feel oneself everywhere at home; to see the world, to be at the centre of the world, and yet to remain hidden from the world - such are a few of the slightest pleasures of those independent, passionate, impartial natures which the tongue can but clumsily define"

How to Choose a Walking Cane or Stickon 08/01/2014

How to Choose a Walking Cane or Stickon 08/01/2014

Michael Miller Fabulous Fabric Swatches for Quilting, Crafts etcon 07/02/2014

Michael Miller Fabulous Fabric Swatches for Quilting, Crafts etcon 07/02/2014

The Drama of Life in the Rock Poolon 06/08/2014

The Drama of Life in the Rock Poolon 06/08/2014

Cycling For Seniors - Cycling In Retirement for Fitness, Fun and Friendson 04/26/2014

Cycling For Seniors - Cycling In Retirement for Fitness, Fun and Friendson 04/26/2014

Comments

Hello WordChazer - That’s such an interesting concept about Virginia Woolfe. Yes, thinking about it, her descriptions are often very cinematic, as though her eyes were sweeping across an urban landscape. Its the flow of someone observing, transposed into literature. Love her writing. I have not read Bellow (must put on ‘To Do’ list).

I had a Masters student client who wondered whether the flaneur was an influence on Saul Bellow's characters. He also wrote in depth about Virginia Woolfe and thought that she was the closest thing to a female flaneur possible in her observations. His essays were a joy to proofread.

Mira - Lovely to get your kind comments. Thank you!

Mari - Thank you so much for your comment. I'm really glad you enjoyed it!

Nice piece, Kathleen! I enjoyed your writing very much :-)

It's also so true that "architecture changes people" -- great points!

Loved this, Kathleen. It was something I knew nothing about and you've covered it very well.