His system of government and administration aped that in England, rather than the traditional ways of the Scottish Gaels. King Robert I retained those burghs and burgesses established by Edward I, then looked towards his Anglo-Norman peers for further inspiration.

His ancestral credentials and stable monarchy attracted traders from the north of England. They came to the markets also initiated by Edward I and demanded that business was conducted in English.

Those Scots seeking to get rich on the proceeds quickly taught themselves and their children the language.

Little by little, the Bruce's Lowland subjects were edged away from their Celtic roots and taught to disdain their native culture as old-fashioned, unprogressive and downright wrong. Embracing the example shown by this new crop of aristocrats, they hoped to find power and prestige by rejecting all that had made them Scottish.

By 1390, no-one south of Stirling spoke Gaelic at all. They were Scots forged in the mold of Robert the Bruce's ancestry, at the expense of their own.

In the northern Highlands, where no Normans had settled and the chieftains retained control of their clans, Scottish culture, traditions and the Gaelic language continued on unabated. Within a generation or two, the Lowland Scots had come to view their compatriots as barbarians, or knuckle dragging idiots, too backward to be considered truly Scottish.

Thus the divide and conquer took hold on the back of a cultural genocide in the south. The far-reaching consequences would eventually return a Scottish king to the English throne, who was indistinguishable from the English aristocracy. And who preferred London to Edinburgh.

Further still, it would facilitate the circumstances which gave rise to Culloden and the Highland Clearances; then would ensnare Scotland politically and economically into an Act of Union.

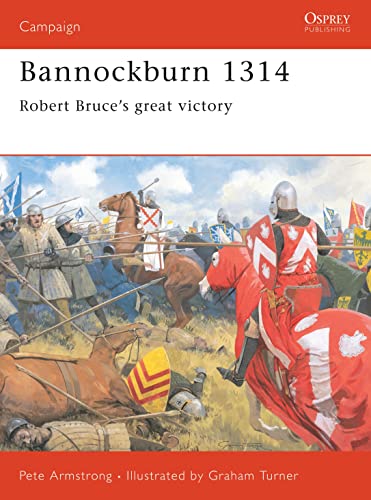

Seven hundred years after Scotland's victory at Bannockburn, it would be necessary for the nation to look for independence again at the ballot box.

The campaign trails would be conducted in English, amongst a population which culturally appears no different to its neighbors south of the border. Not because Scotland ever wished to become England, but because the rule of Robert I was not fundamentally different to what may have been expected under Edward II.

Both countries simply became Anglo-Norman, and that looked the same regardless of their location relative to Hadrian's Wall.

Who won at Bannockburn? Robert the Bruce and the descendants of the Norman conquerors. What did they win? Scotland, and the completion of the Anglo-Norman conquest of Britain.

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Comments

Even as late as the 6th century, I was finding hints of this. It was while I was researching the story of Maelgwn Gwynedd. He was said (twice) to father children with Pictish princesses/queens (obviously using modern terminology there), because he was such a strong leader. It wasn't his leadership needed - he never became king - but his seed for the future monarch thus sired.

The cultural connection between Brigantes and Picts can be inferred from the story of Cartismandua. Both seem to have used matrilineal inheritance of the throne.

In the late sixties Cartsmandua was going to dispense with her husband Venutius and get his armour bearer, Velocratus, as a new lover. In a patrilineal/patriarchal society that does not happen. The king kills the rival, and the queen, if she is lucky, gets away with her life [e.g. Henry 8th, whose queens were not lucky.] But in a society where there is matrilineal inheritance and where the queen is the representation of the goddess of sovereignty, husband replacement can and does happen, and the previous husband is often sacrificed. Husband replacement seems to have been happening in Brigantia in the sixties prior to the Roman arrival. If we look further back into the history of the Isles we note the existence of Maeve of Connaght,a sovereign queen if ever there was one. It is thought that bog bodies in Ireland were sacrificed kings, indicating a widespread matrilineal/matriarchal system . I wonder whether Boudicca was such a queen.

The matrilineal system found among the Picts is to my mind the remnant of the older way of doing things in the Isles before the arrival of Celtic culture, which used patrilineal inheritance. It seems to have been operating among the Brigantes in the first century, so there could have been affinities between Brigantes and Picts, and this may have been the case with some Britons North of the Wall as well.

Note also that in modern times there were two islands that had queens: Handa and Hirta [St Kilda.] These women had a social/ritual function, and were the successors of the ancient Pictish sacred women

Cartismandua was long dead by 367, but she could have had a successor, indeed would have done.

OOohhh! This makes a lot of sense. As soon as you said Brigante, I thought of Cartismandua. She would have certainly had the clout and the contacts to support something like that. And there is so much trickle-down anecdotal evidence of the matrilineal sovereignty of the Picts. I've just never thought of the Brigante and the Picts in the same context before.

Stuart Laycock, writing in Britannia, the Failed State, suggests that some of the Picts who raided in the South of England during the troubles of 367-369 might have been Brigantes, who themselves were painted. Note that the Picts were said by Bede to have a matrilineal system of inheritance, with the sovereignty passing through the female. There seems to be a parallel between this and the Brigantes of Yorkshire, whose queen Cartimandua seems to have been able to select and put aside husbands as she saw fit, which explains the troubles with Venutius which led to the Roman intrusion into Northern England. Thus there is a valid case to be made that elements of Pictish culture spread further south than the kingdom of the Picts located in Alba, even among peoples who were accounted Britons and who spoke the British language.

Calanon - I knew you'd clarify this! That substantial British land north of the wall is what I was remembering. Though I thought it was Pictish.

Then again, I tend to think of the Picts as being pretty much Brythonic with a new label stuck on them by the Romans. Is that too simplistic? As you can tell, my field of expertise tends towards those living further south and west... or Wales as we know it today.

I keep asking Audioworm for my time machine. He's given up telling me that the Physics don't add up.

Good points, Calanon! I question whether the definitions of Pict was as clear as we would like to think. Certainly there were Britons North of the wall, else Cumbric would not have been spoken there. But the distinction between Pictish and Brythonic culture may not have been as clear as some would think, particularly as you went further north. The cultural boundaries may have been more of a continuum than a rigid division. I believe that this is the case with the division between Scotland and England. For example, as a Northern Englishman I feel culturally somewhere between Southern Scotland and Southern England.

You are probably right that Pictish was related to the Brythonic tongue, but there is the problem that it differed enough from the British language for Bede to regard the two as different tongues, while he did not distinguish Cumbric from its relative Welsh.

I note that your self description is historian and nerd. That's great. I like nerds.

I don't want to get too into this just yet as I'm going to start studying pre-Roman Britain and Roman Britain in September, however with Hadrian's Wall from all the maps I can find Hadrian's Wall was not built through the centre of Pictland as there was substantial amount of land occupied by Britons north of the wall: http://www.oldthingsforgotten.com/map...

with the four groups between Hadrian's Wall and the Antonine Wall being primarily Brythonic.

As to the Pictish language, it appears most people accept it as a branch of the Brythonic languages but nobody is certain. Why can't time machines exist? It'd make certain things much easier...

Hadrian's Wall was built straight through the centre of Pictland. People assume it was on the edge of Friendly Territory, but you'd have never got the wall up, if that was the case. It was mostly constructed by British slave labour, but with the full collusion of local chieftains.

Assigning Celtic credence is always problematic, due to what's meant by 'Celtic'. Brythonic and Gaelic/Gallic normally covers it. As you said, Scotland has so many other cultures in the mix, but then so did Ireland, particularly in the Pale. Man is worst of all. That's been completely overwhelmed by Britons, Norse, then Gaels.

I'm going to ask my friend Calanon to pop into this thread. I think he'd have useful things to add.

How far is Scotland a Celtic state? The people of the North descend from Picts, who were ancient Britons; Irish settlers, who dominated the Picts to found the kingdom of Scotland; and Norse. In the south there were Britons and Angles. Let us also note that after the departure of Rome the garrisons on the Wall survived and they were descended from a variety of races [ Sarmatians, Gauls, Moors etc.]

The linguistic situation is complex. Pictish, which Bede distinguishes from Gaelic, died out. Gaelic dominated much of the north, but Norn was spoken until the twelfth century in the North Hebrides, and it still influences the vocabulary of Fair Isle. Cumbric in its various dialects was spoken further south, and Lallans English was powerfully present north of the Wall. This was related to Northumbrian.

Prebble's book broke my heart when I read it. More so than his book on Culloden, but only because I expected what I was going to read there.