Nevertheless, there are a couple of intriguing - and perhaps interlinked - clues:

Peibo Clafrog (aka Peibio Clafrog, Pepiau Glavorawc, Peibiawn Glawrawc, Pepianus Spumosus) ruled Ergyng a generation before St Tydecho was knocking about. His epithet is generally translated as 'scabby', 'dribbling' or 'leprous', and relates to the fact that he couldn't stop dribbling.

He tried to drown, then burn alive his pregnant daughter Efrddyl. She not only survived both with barely a blink, but gave birth in the pyre, calmly nursing her baby boy as the flames licked harmlessly around them. The baby became St Dyfrig - contemporary bishop with Tydecho - and cured his psychopathic grandfather's affliction. (St David also nipped by to cure Peibio's blindness.)

Garthbeibio and Ynys Beibio are both said to be named after him. Though no records explain why a ruler in what's now Herefordshire, Gloucestershire and Gwent should have scattered his moniker over landmarks in Powys and Gwynedd.

Peibio, as mentioned in the Welsh legend Culhwch and Olwen. He and his brother Nynnio were both insane kings, who weren't content to rule only their kingdoms, but wanted to own the galaxy too. The giant Rhita Gawr - whose stomping ground was Snowdonia - had enough of their arrogance, so turned them both into oxen.

In the 17th century, the bard Iolo Morganwg composed Triads about the legendary Hu Gadarn, who shackled Peibio and Nynnio to yokes, in order to use their strength to drag the monstrous Afanc out of the Lake of Floods. Thus Wales was saved from inundation and the Welsh were introduced to the concept of ploughing.

Though half of Wales claims to have the afanc's lake in their vicinity, there is one contender close by Garthbeibio. Llyn Llion is sometimes said to be an alternative name for Llyn Tegid, or Bala Lake, just over the mountain. From there the creature was said to have been dragged into Cwn Ffynnon, which is located above Llanmawddwy, just up the valley and around the hill from where Gwely Tydecho may be found.

So maybe an obscure Beibio link lies there, lost in the depths of a remote mountain lake. After all, the Afon Twrch flows by there too.

John Davies was once rector here - a man hugely associated with the Welsh renaissance; a collection - and preservation - of Welsh legends; and his assistance to William Morgan in writing the Welsh Bible, a feat largely credited with the survival of the Welsh language.

John Davies was once rector here - a man hugely associated with the Welsh renaissance; a collection - and preservation - of Welsh legends; and his assistance to William Morgan in writing the Welsh Bible, a feat largely credited with the survival of the Welsh language.

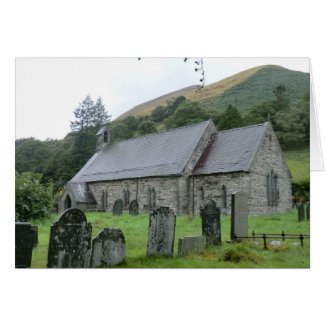

Over the centuries this location has variously been recorded as Kemeys, Cemmes, Cemais, Cemmaes and more besides. It translates as 'bend in the river', i.e. Afon Dyfi flowing right alongside the church.

Over the centuries this location has variously been recorded as Kemeys, Cemmes, Cemais, Cemmaes and more besides. It translates as 'bend in the river', i.e. Afon Dyfi flowing right alongside the church.

The church itself is surrounded by yew trees, only four of which are truly ancient. The rest were planted by the Victorians, presumably because the ones they cut down weren't neat enough.

The church itself is surrounded by yew trees, only four of which are truly ancient. The rest were planted by the Victorians, presumably because the ones they cut down weren't neat enough.

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Madness! Mexican Gay Wedding Blocked by Christian Agitators Challenging Grooms' Sanityon 01/12/2015

Madness! Mexican Gay Wedding Blocked by Christian Agitators Challenging Grooms' Sanityon 01/12/2015

Comments

JoHarrington, Thank you for the practical information and product lines.

Is there a story that tells what happened to the Exalted Ox on the Cemaes mountain ridge?

It is apparent you know this quite well.

Oooh! I hadn't connected the actual physicality of the tree, other than its longevity. Yes, you're absolutely spot on. I love it when new angles come in to long known stuff.

Jo, you set me off on a train of thought when you said that yew trees were useful meeting places. As a horticulturalist I think about plant characteristics. Two characteristics make the yew suitable. It has branches that spread wide, meaning that many people can be sheltered under them; and as the tree is toxic,its shed leaves and arils [berries] are toxic also, so little grows on the ground under its canopy, ensuring that there was an unimpeded place for people to sit.

My understanding was that the yew pre-dated them all, insofar as anyone can tell. A yew was a useful place for meetings, when nomadic tribes drifted far and wide. Simply because they could practically guarantee that it would still be there. Then standing stones or circles began to mark the same spots as being even more permanent. (Obviously much theorizing going on here, because who can tell for certain?)

But yes, Ronald's work is always worth reading.

The tree that links worlds is a theme full of mythological significance. I was unaware that in Welsh myth the yew had this function, but the yew's presence in English churchyards would indicate that a Celtic idea carried on into the Saxon period.The linking of the Middle Earth with heaven was being symbolized in this practice.

Ronald Hutton, writing in Pagan Britain, says that the neolithic folk avoided activity on Caburn hill in the South Downs and links this avoidance to the fact that the summit has been shown to have been covered in yew trees. The site was too holy to touch. So the yew has been venerated in this isle for a very long time indeed, for it was an idea that seems well established in the neolithic period, so must be older, maybe mesolithic.

A badge on your profile means that you've received three Editor's Choice awards. Well done!

The thing with yews is that they're so long lived. They can exist around 1000 years or more and so feel very sacred. Plus they're poisonous. Life and death in one big beautiful tree. There are Welsh traditions whereby the yew can act as a ladder between the worlds.

Hawthorn is sacred to the goddess, particularly the May Queen. She marries the Oak King then.

On my screen there is a badge. However, I did receive an email telling me that I have a badge on my profile and when I looked it up you have the same.

The idea that you proffered, that the sacredness of yew predates druids, is one that has weight to it. While the druids revered trees, their main tree was the oak, even their name derives from the Celtic term for oak. That the sacred status of oak faded with the ebbing of druidry, while the sacred status of yew did not, suggests that yew's sacredness derives from different sources, and I suggest that it is deeply rooted in British prehistory, so deeply that it was taken into the new Christian cultus.

Hawthorn is the same. Sacred to the goddess, hawthorn trees can often be seen in the middle of ploughed fields, as some farmers still won't risk the bad luck that comes from felling them. This is a belief that almost certainly goes back to the neolithic age or before.

Did I momentarily have an Editor's Choice award? I don't see one now. LOL But I'll take the spiritual one, awarded by you.

I've missed Wizzley too. It's been a little chaotic in real life, plus I've been building up my Zazzle stores. I have a pile of articles to write here though, so hopefully I'll get more time to do so hereon.

The antiquity of some of Britain's heritage yew trees has to pre-date Christianity. I'm sure some pre-date the Druids too.

Oooh! It honestly hadn't occurred to me that Beibio could have been a Pagan deity! That opens up a whole new ball-game. Thanks for the imput. It's moments like this that I remember why I like chewing these theories over with you so much.

Congratulations on your well deserved editor's choice, It was so good to read another of your articles on matters Celtic and spiritual. You have not written as much recently and I have missed you.

Yew trees are an enigma. Some claim that yews on ancient church sites are pre-Christian, which is what I think, but some think them a Christian input to signify eternal life. But there is no ground in Christianity to make the yew sacred, so in my opinion they are of pagan origin and are part of that unique British way of expressing Christian devotion with pagan cultural elements that makes these isles so interesting.

The link between pagan sites and subsequent Christian churches is evident in the Tydecho churches.

Beibio and Tydecho. As you know several Christian saints are Celtic deities, and we have agreed before that Tydecho and is Tegfedd were in this category. Beibio may be another Celtic deity. It was well known for the culti of pagan deities to become conflated with each other, with one dominating the other and reducing it to almost nought, and this may have happened with Beibio. You wonder about how a ruler from Herefordshire and Gloucestershire should have markers in Wales. I suggest that Western England and Wales are only distinct entities on maps, and they phase into each ethnically and culturally. There are people in the West of Hereford who feel more Welsh than English. Beibio may have been an ancient deity across West Britain whose name lingers in disconnected sites.