Sandy, Bedfordshire, southeast England: Tom (orangeaurochs), CC BY 2.0, via Flickr @ https://www.flickr.com/photos/orangeaurochs/6018797826/

closeup of antennae, left eye, labial palpi and proboscis of Pieris rapae: Richard Bartz, Munich aka Makro Freak, CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pieris_rapae_head_Richard_Bartz.jpg

c.1860 photograph; G.R. Agassiz, ed, Letters (1913), opp. p. 44: Not in copright, via Biodiversity Heritage Library @ ; via Internet Archive @ https://archive.org/details/lettersrecollect00agasuoft?view=theater#page/n68/mode/1up

1920 statue by Carl Eldh (1873-1954), Cleveland Museum of Natural History, Cleveland, northeast Ohio: Daderot, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cleveland_Museum_of_Natural_History_-_Carolus_Linnaeus_by_Carl_Eldh.jpg

Bas-Saint Laurent, southeastern Quebec, east central Canada: Gilles Gonthier, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr @ https://www.flickr.com/photos/gillesgonthier/538719541/

cabbage white egg: Harald Supfle, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pieris_rapae_-_egg_01_(HS).jpg

cabbage white eggs on leaf: Tom Wess (Dr. Murke), CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pierisrapae1.jpg

Son Carrió, Mallorca: Pau Cabot, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Taperera.jpg

Commanster, Belgian High Ardennes, Walloon region, southeast Belgium: James Lindsey at Ecology of Commanster, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Pieris.rapae.caterpillar.jpg

cabbage white pupa just before emerging: Entomart (Entomart.ins) www.entomart.bel, Use for any purpose provided that the copyright holder is properly attributed, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Pieris_rapae_pupa.jpg

pupation: Harald Supfle, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pieris_rapae_-_puppa_01_(HS).JPG

newborn: Drahkrub, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pieris_rapae_hatched_(dkrb).jpg

Ausseerland (also: Ausseer Land;Region Bad Aussee), northwest Styria, southeast Austria: Michael Gasperl (Migas), CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pieris-rapae(Filzmoos).jpg

Roßthal (southwestern suburb of Dresden), Saxony, east central Germany: Olaf Leillinger, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pieris.rapae.6834.jpg

"Two Bees on a Creeping Thistle (Cirsium arvense): Richard Bartz, aka Makro Freak Munich, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Cirsium_arvense_with_Bees_Richard_Bartz.jpg

North Frisian Island of Amrum (Öömrang dialect of North Frisian: Oomram), Schleswig-Holstein, Germany's North Sea coast: Matthias Bigge, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Falter-IMG_0578.JPG

New England asters attract butterflies, such as Pieris rapae and monarchs (Danaus plexippus): Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Monarch_Butterfly_on_New_England_Aster_by_Rick_L_Hansen_(4515058100).jpg

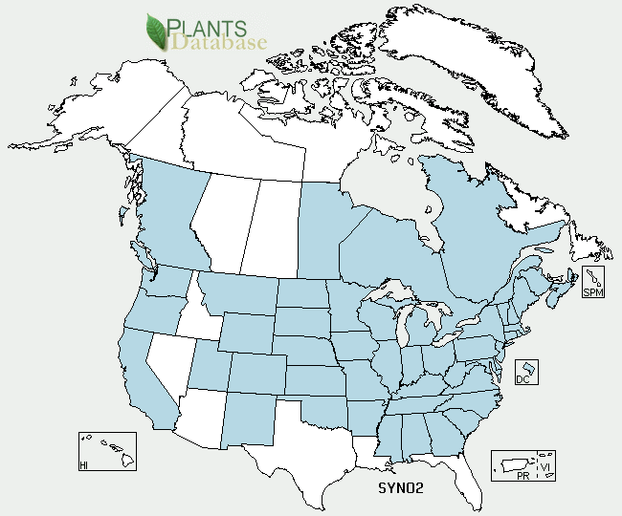

native Canadian provinces: British Columbia, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Quebec: USDA National Resource Conservation Service, via USDA PLANTS Database @ http://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=SYNO2&mapType;=nativity

Pennsylvania's New England asters: Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources - Forestry Archive, Bugwood.org, CC BY 3.0 U.S., via ForestryImages @ https://www.forestryimages.org/browse/detail.cfm?imgnum=5021085

Austins Ferry, Tasmania, Australia: JJ Harrison, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Pieris_sp_3.jpg

"A collective salt lick of Small Whites, Pieris rapae, on alternate-soaked sandy clay (dried pool).": Christian Fischer, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:PierisSaltLick.jpg

Hamburg, northwestern Germany: Quartl, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kleiner_Kohlweissling.jpg

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Comments