Malacosoma americanum commonly is known as Eastern tent caterpillar.

• In boom population years, these caterpillars are despised for the devastation that they wreak, especially upon black cherry (Prunus serotina) and apple trees (Malus domestica).

• Their inadvertent involvement in Mare Reproductive Loss Syndrome is highlighted.

Eastern Tent Caterpillars: Early Spring Campsites in Black Cherry and Apple Trees

Eastern tent caterpillars announce spring in their own style, sometimes via a population explosion.

Malacosoma americanum is commonly known as the Eastern tent caterpillar. As with most insects, being a univoltine, oviparous species, its adult moth has one generation per year (univoltine) which emerges from eggs laid by their mother soon after fertilization (oviposition). Trees in the Rosaceae family, primarily cherry (Prunus) and apple (Malus), are the chosen sites of oviparity. About two hundred to three hundred eggs are oviposited, usually on a twig, in a single cluster from late spring to early summer.

Embryogenesis: The rush towards pleasant idleness, dolce far niente

Although the developmental process from fertilization to fully formed embryo (embryogenesis) is completed rapidly within about three weeks, the caterpillars then basically quiesce and overwinter quietly within the egg cluster. The accelerated rate of embryonic development is rewarded with a lengthy period of pleasant idleness, dolce far niente (“sweet to do nothing”).

The next spring heralds the end of their embryonic dormancy and their graduation into larval life (Latin: larva, “ghost”). The caterpillars chew through their egg shells and perfectly time their emergence with the budding of their host trees. Their larval life, which is the journey from embryo to moth, is characterized by six developmental stages (morphogenesis) as nymphs (instars).

Campsite priority: Set up tents

After emergence, the caterpillars’ priority entails building their communal tent. Eastern tent caterpillars have a spinneret, which is an organ that spins silk, a protein fiber, for constructing their tent. Built in tree or branch forks, their communal dwellings typically orient their broadest expanse to the southeast to derive the benefits of the morning sun. The commune has openings for entrances and exits.

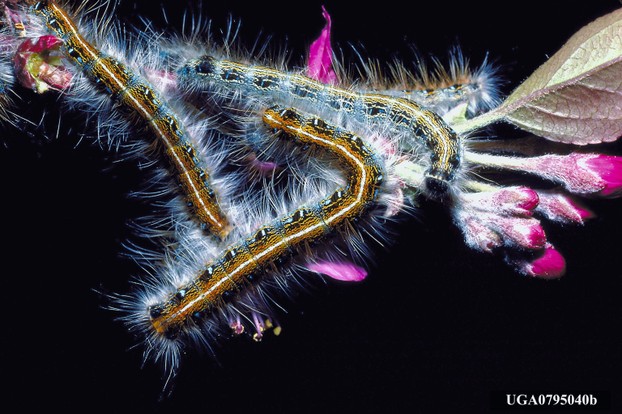

Whether forming a food procession or basking en masse, Eastern tent caterpillars are conspicuous. Down their dorsal side streaks a thin white line that is flanked with a line of yellow, red, or orange coloring that is outlined in black with a side row of blue ovals. Their exterior is covered with setae (fine hair) that are barbed.

Never-ending home renovations: Keeping pace with growth spurts

Daily expansions in the tent, sometimes measuring two feet (0.6 meters) in length, characterize most of their larval life, as their thrice daily feedings, up through the fifth instar, require ongoing home renovations proportionate to the caterpillars’ expanding girth. The tent sometimes expands to measure almost two feet in length. Ideally these juveniles foray forth for their foliate comestibles before dawn, at mid-afternoon, and after sunset.

Their favored apple and cherry leaves contain cyanogenic glycosides from which hydrogen cyanide (HCN) is released by stressor damage (cyanogenesis), such as consumption (herbivory), trampling, or wilting. Eastern tent caterpillars are not troubled by cyanide poisoning, but if they feel stress, whether from perceived threats or physical disturbance, they vomit cyanide-laced juices that are toxically, even fatally, unpalatable in large quantity to animals, including birds.

Moreover, most birds are repelled by the hairy bodies of these caterpillars. Not so with the yellow billed cuckoo (Coccyzus americanus [Linn.]) and the black-billed cuckoo (Coccyzus erythrophthalmus [Wils.]), whose delight in caterpillars extends to the hirsute variety and who devour Eastern tent caterpillar delicacies in steps, akin to the process that humans are willing to undergo in extracting lobster meat:

“. . . .In the early part of May I observed that the apple trees in my orchard were greatly infested by tent caterpillars. . . .I saw a Cuckoo busily engaged among some caterpillars’ nests. . . .it was found to be picking out the larvae and squeezing the juices from the body between its mandibles, then dropping the skins to the ground. The orchard seemed to be alive with these plain colored birds. By noon none were to be found, nor were there any caterpillars left. Every nest had been torn to shreds and the insects were all killed. . . .” (Amos William Butler, p. 55)

Silk from their spinneret is secreted even as these caterpillars forage away from the tent to their food source. Thus regularly traveled routes are soon littered with silk droppings. Nevertheless, these silky pathways do not serve as trail markers for hungry caterpillars.

Rather, they mark their food routes with a food trail chemical, pheromone (Greek: φέρω, phero "to bear" + ὁρμή, hormone "impetus") from the posterior tip of their abdomen.

In the sixth and last stage of larval life, the instar begins breaking with its traditional patterns. Reducing its food forays to once a day, the sixth instar, now up to two inches (5.08 centimeters) in length, ventures out for only nocturnal grazing. Furthermore, their tent building ceases, as their silk is now promised for their cocoons. After over six weeks of feeding, the time of communal living is coming to a close.

Cocoons: The place of transformation

The sixth instars disperse to select new stomping grounds, protected places where they build their individual cocoons. Tightly swathed in their silk cocoon, they enter the immobile pupal stage (Latin: pupa, “doll”) of their existence.

The pupal stage is the third of four stages in the life cycle of holometabolous (Greek: hol, “whole” + metabolē, “change”) insects, which are insects that exhibit a significantly different appearance between their larval and adult (imago: Latin for “image”) stages by way of the transformative pupal existence.

External immobility masks a massive cellular cataclysm: larval morphology (Greek: μορφή, morphé “form” + λόγος, lógos “word, study, research”) is dissolved through internal digestion while the morphologic features of the new adult are growing from imaginal discs, which are tissue clusters that formed during the embryonic stage but remained dormant during larval life.

Metamorphosis: The one-day life of the Eastern tent caterpillar moth

About two weeks later the Eastern tent caterpillar moths emerge from their cocoons. They are red brown in color, and there are two white bands on their front wings (forewings).

Their life is brief and is targeted to perpetuation of the species. The females mate, they oviposit, and then they die, with all of these events occurring typically within one day.

Eastern tent caterpillars: Pesky for their unsightly tents or troublesome catalyst in Mare Reproductive Loss Syndrome

Although their tents are conspicuous and unsightly announcements of their presence, Eastern tent caterpillars are generally innocuous plant pests, with their impact mainly being restricted to cosmetic damage. Their host trees usually refoliate branches that have been stripped by the ravenous nymphs. Their wriggling masses may detract from the overall effect of the budding beauty of their host trees, but apart from possible cyanide poisoning from consuming them -- and who would want to eat them? -- they are harmless to humans.

The gravity of their impact, however, increases with respect to horses. From late April to early May in 2001, the horse industry in the Ohio Valley experienced a devastating catastrophe as, within the space of a few weeks, over 3,000 pregnant mares suffered early fetal loss, through stillbirth and abortions, and gave birth to sick foals with a high mortality rate. Subsequently named Mare Reproductive Loss Syndrome (MRLS), its incidence mysteriously spiked at farms with a profusion of black cherry trees (Prunus serotina) and Eastern tent caterpillars. Further research revealed that spring 2001 exhibited an unusual weather pattern of a severe frost and drought preceded by an unseasonably warm spell. This situation echoed similar conditions two decades earlier in spring 1981; at that time, though, the unusually high rate of pregnancy loss was attributed to fescue toxicosis, which stems from consumption by pregnant mares of tall (Festuca arundinacea) fungally infected by Acremonium coenephialum.

Subsequent experimental administration of Eastern tent caterpillars orally to pregnant mares revealed that only exoskeletal, hairy parts induced late-term abortions and early fetal losses. Research continues to determine the causative mechanism, with one theory being that bacteria (mainly streptococci and actinobacilli) in the pregnant mares’ digestive tract escapes into the uterus through punctures incised by the caterpillars’ barbed hairs.

Tents contain an accumulation of exoskeletons that are shed successively from the first to the sixth instar by each caterpillar. Embedded in the exoskeleton are the caterpillar’s barbed hairs. Abandoned tents eventually disintegrate and fall out of the trees. Then the lightweight, hairy exoskeletons, which are wafted into nearby pastures on the affected farms, are consumed by horses as they graze.

Equine Amnionitis and Foetal Loss (EAFL): An analogous syndrome in Australia

According to Dr. Max Wilson and Dr. Robyn Woodward of Equivet Australia, who journeyed to Lexington, Kentucky, for first-hand information on MRLS, an analogous syndrome, Equine Amnionitis and Foetal Loss (EAFL), is found in Queensland and the Hunter Valley region of New South Wales in Australia. The Aussie culprits, the processionary caterpillar (Ochrogaster lunifer) and the white cedar moth caterpillar (Leptocneria reducta), dwell in the acacia and eucalypt species of eastern Australia.

Control of Eastern tent caterpillars

Those who feel that they simply cannot abide Eastern tent caterpillars may choose from an array of annihilatory treatments, chemical as well as natural.

Generally reserved for cases of extreme infestation, insecticides are applied in early spring. Frequently used insecticides in the United States include:

- Acephate,

- Bacillus thuringiensis (B.t.),

- Carbaryl (Sevin),

- Esfenvalerate,

- Malathion, and

- Permethrin.

Breaking the incipient tents into pieces by dousing them with the jet spray feature of a garden hose in early spring is a less invasive, nonchemical control.

Natural enemies include insect parasitoids, which attack the egg stage of their host. Chalcid wasps in the superfamily Chalcidoidea are insect parasitoids of Eastern tent caterpillars. So one method of control is to move the egg clusters to a location away from host trees. After destroying the caterpillars’ eggs, chalcids move on to their next host victims.

Tachinia flies, which are in the family Tachinidae and are often called tachinids, are also parasitoid enemies of Eastern tent caterpillars. Tachinids, thus, comprise another natural control against infestation by Malacosoma americana.

Humans are also natural enemies. As pointed out by Washington State University’s Whatcom County Extension:

“Natural enemies (wasps, flies and disease) will continue to build large populations this year and next, soon bringing tent caterpillars under control again. This phenomenon, in conjunction to climate, reinforces the cyclical nature of tent caterpillars. In the mean time, continue squishing, stomping, and pinching them as they come. You too are a natural enemy of tent caterpillars!”

Conclusion: Unavoidable decisions in bumper years for tent caterpillars

In bumper years, when Eastern tent caterpillars' webs abound and the landscape moves with the wrigglings of emergent, exploratory caterpillars, decisions demand attention.

- Will the completely natural choice -- with acceptance of life's natural courses and, therefore, of the population explosion -- triumph?

- Will non-chemical intervention entail tent destruction by way of such strategies as water blasting with garden hoses?

- Will non-chemical intervention be achieved through foot contact to squish and stomp or through tools such as fly swatters?

- Will chemical strategies prevail?

In quiet years, with low populations, a casual attitude of laissez-faire may be adopted with ease. But, in bumper years, when arboreal branchings and foliage cannot be seen for the multi-layered webbings and when lawns and pavements are alive with larval multitudes, strategies -- even the choice to do nothing -- require consideration. Sometimes the ultimate decision may not be so much a testament of personal pro-or-con environmentalism as a reflection of least time-consuming option in busy lives anxious to minimize distractions from precious enjoyment of springtime.

Acknowledgment

My special thanks to talented artists and photographers/concerned organizations who make their fine images available on the internet.

Image Credits

Eastern tent caterpillar, at EF 100mm Macro @ f/5.6: brian.ch, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr @ https://www.flickr.com/photos/zomgitsbrian/3594051842/

Eastern tent caterpillar Malacosoma americanum (Fabricius): Robert L. Anderson, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org, CC BY 3.0 U.S., via Forestry Images @ https://www.forestryimages.org/browse/detail.cfm?imgnum=0590063

northwest of intersection Heald Road and Kimball Hill Road, Hillsborough County, southern New Hampshire: J.R. Carmichael, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Eastern_Tent_Caterpillar_(tent_close).JPG

black cherry trees (Prunus serotina Ehrh.), favored hosts for Eastern tent caterpillars: Terry S. Price, Georgia Forestry Commission, Bugwood.org, CC BY 3.0 U.S., via Insect Images @ https://www.insectimages.org/browse/detail.cfm?imgnum=2733040

Image type: Field; Image location: United States: Lacy L. Hyche, Auburn University, Bugwood.org, CC BY 3.0 U.S., via Insect Images @ https://www.insectimages.org/browse/detail.cfm?imgnum=1540462; via Forestry Images @ https://www.forestryimages.org/browse/detail.cfm?imgnum=1540462

Eastern Tent Caterpillar Moth: Doctorkilmer, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Malacosoma_americanumfemale.jpg

Eastern Tent Caterpillar Moth: Doctorkilmer, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Malacosoma_americanummale.jpg

Image type: Field; Image location: United States: USDA Forest Service - Region 8 - Southern, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org, CC BY 3.0 U.S., via IPMImages @ https://www.ipmimages.org/browse/detail.cfm?imgnum=1512056

Eastern Tent caterpillar, Malacosoma americanum: Megan McCarty (Meganmccarty), CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Eastern_Tent_caterpillar,_Megan_McCarty64.jpg

amazing layers of Eastern tent caterpillar web: woodleywonderworks, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr @ https://www.flickr.com/photos/wwworks/477080513/

St. Louis, east central Missouri: Andy Reago & Chrissy McClarren, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:-_7701_–_Malacosoma_americana_–_Eastern_Tent_Caterpillar_Moth_(14290943841).jpg

Image type: laboratory; Image location: United States: Gerald J. Lenhard, Louisiana State University, Bugwood.org, CC BY 3.0 U.S., via Forestry Images @ https://www.forestryimages.org/browse/detail.cfm?imgnum=0795040

Sources Consulted

Barceloux, Donald G. Medical Toxicology of Natural Substances: Foods, Fungi, Medicinal Herbs, Plants, and Venomous Animals. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2008.

Butler, Amos William. The Birds of Indiana: With Illustrations of Many of the Species. Greencastle, IN: Indiana Horticultural Society, 1890.

“Eastern Tent Caterpillar Moth: Malacosoma Americana.” Fairfax County Public Schools > Island Creek Elementary School > Study of Northern Virginia Ecology. Fairfax County Public Schools. Web. fcps.edu

- Available at: http://fcps.edu/islandcreekes/ecology/eastern_tent_caterpillar_m.htm

“Equine Amnionitis & Foetal Loss: Mare Abortions & Caterpillars.” Equivet Australia: Wilson’s Equine Veterinary Services > Horse Talk. Equivet Australia. Web. equivetaustralia.com

- Available at: http://www.equivetaustralia.com/horse-talk/equine-amnionitis-foetal-loss.html

“Fescue Toxicosis in Horses.” Cornell University Department of Animal Science - Plants Poisonous to Livestock. Cornell University. Web. www.ansci.cornell.edu

- Available at: http://www.ansci.cornell.edu/plants/toxicagents/fesalk.html

Fitzgerald, Terence D. The Tent Caterpillars. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995.

“Mare Reproductive Loss Syndrome (MRLS).” The Western Horse Showcase > Features > Medical Articles. Australian Western Horse Showcase. Web. australianwesternhorseshowcase.com

- Available at: http://www.australianwesternhorseshowcase.com.au/Features/medical/MRLS-MARE-REPRODUCTIVE-LOSS-SYDROME.htm

Meyer, John R. “Insect Development: Embryogenesis.” North Carolina State University College of Agriculture & Life Sciences > General Entomology 425. Last updated January 24, 2007. John R. Meyer. Web. www.cals.ncsu.edu

- Available at: http://www.cals.ncsu.edu/course/ent425/tutorial/embryogenesis.html

Meyer, John R. "Insect Development: Morphogenesis." North Carolina State University College of Agriculture & Life Sciences > General Entomology 425. Last updated January 24, 2007. John R. Meyer. Web. www.cals.ncsu.edu

- Available at: http://www.cals.ncsu.edu/course/ent425/tutorial/morphogenesis.html

Miller, Haven. “Foaling and Breeding Is Normal Among Horses Affected by Last Year's MRLS Problem.” University of Kentucky College of Agriculture, Food and Environment > News Releases > News Archive. March 21, 2002. University of Kentucky College of Agriculture. Web. www2ca.uky.edu

- Available at: http://www2.ca.uky.edu/newsreleases/2002/Mar/normal.htm

Peterson, Steven C., Nelson D. Johnson, and John L. LeGuyader. “Defensive Regurgitation of Allelochemicals Derived from Host Cyanogenesis by Eastern Tent Caterpillars.” Ecology, Vol. 68, No. 5 (October 1987): 1268 - 1272.

Virginia Cooperative Extension-Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University. Pest Management Guide 2011: Home Grounds and Animals. Publication 456-018. Blacksburg VA: Virginia Cooperative Extension, 2011.

Virginia Cooperative Extension-Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University. Pest Management Guide 2014: Home Grounds and Animals. Publication 456-018. Blacksburg VA: Virginia Cooperative Extension, 2014.

- Available as PDF at: http://pubs.ext.vt.edu/456/456-018/456-018.html

“Western Tent Caterpillar Update: Biological Control.” WSU Whatcom County Extension > Pest Pages. Board of Regents, Washington State University. Web. whatcom.wsu.edu

- Available at: http://whatcom.wsu.edu/ag/homehort/pest/tent_caterpillar_biocontrol.htm

Gus Caterpillar Climb-N-Crawl Tunnel by ECR4Kids ~ Available via Amazon

Product size: 85.5 inches L x 42.5 inches W x 39.5 inches H; Opening: 17 inches.

|

| ECR4Kids GUS Climb-N-Crawl Caterpillar Tunnel | Indoor and Outdoor ... |

Caterpillars of Eastern North America: A Guide to Identification and Natural History by David L. Wagner ~ Available via Amazon

|

| Caterpillars of Eastern North America: A Guide to Identification an... |

You might also like

Spring Fever: Restless Brown Marmorated Stink Bugs Stumble ForthBrown marmorated stink bugs (Halyomorpha halys), as they shrug off their wint...

Sea Walnut Comb Jelly: A New World Native That Has the Old Wor...The accidental odyssey of the sea walnut comb jelly from the New World eastwa...

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Comments

Cazort, Yes, manicured properties attract generalists such as starlings and discourage specialists such as cuckoos.

Habitat always can make a difference. It's both disheartening and heartening to witness the results of a bird's eye view of the ground below. For example, stretches of turf tend to discourage songbirds because of their lack of diverse food sources, ground cover, and running water (except for fountains right out in the open) for foraging, mating, raising families, and resting.

As you observe, streams are particularly important in providing habitat. It's critical to have at the bare minimum dense shrubbery and scattered trees. Such an environment provides the prey and protection which specialists look for when habitat-shopping.

I wasn't aware of the toxicity to horses; this was interesting to read about. Normally I think of these as a temporary annoyance that causes unsightly damage which trees usually recover from quickly.

I've been aware that yellow-billed Cuckoos will go wild on them too. I wonder if there are any things that people can do to encourage Cuckoos to nest in an area, and thus help to naturally control the caterpillars. I think Cuckoos tend to prefer dense shrubs and scrubby areas, especially along streams, and I wonder if landscaping practices that involve keeping properties carefully manicured, removing the dense undergrowth, may keep these birds away. Maybe there could be a benefit to letting things get a little overgrown here and there, or planting native shrubs to mimic their natural habitat. I've read about people restoring the riparian vegetation (growth along streambanks) in areas where these birds have been eliminated, and having these birds move back in in as little as three years.