When I finished my A-Levels, it was pretty much a given that the female school-leavers would work in an office or a shop. When Emily Wilding Davison reached maturity, it was expected that she would be a governess or a teacher. Those were our options, though I had the potential for more with a bit of effort. She did not.

We both opted for further education, in order to boost our opportunities. My first degree was free, paid for by the local authority. Emily had to work full-time as a governess to pay her college fees. I was able to attain my Master's Degree. There's nothing (except cash and inclination) stopping me pursuing a doctorate; maybe even a professorship too. All of these were unattainable for Emily.

She was restricted by her gender. She could reach no higher than college. At that point, her zest for learning was promptly stifled. No formal avenues were left open to feed her intelligence with academic stimuli.

In those circumstances, it would take an insanely optimistic person not to sink a little into resentment, pity and boredom, particularly as her male class-mates could carry on. Even where their grades were lower than her own, a university education beckoned for the boys.

I ended up (assuming that I've stopped formal education for good now) two academic levels higher than Emily did. In both of our cases, culture has played a part in where we stopped. Emily had no choice. Her gender dictated where the glass ceiling sat. She would have loved to have continued, but the option wasn't there.

For me, gender is no barrier to education. But arguably social class is. I live in a predominantly working class area, which isn't exactly teeming with graduate level employment. I tried when I achieved my first degree. Part of the reason that I took my Master's was to elevate myself a little higher, in the hope of that lucrative employment. There was still nothing there.

This is where inclination kicks in. Why bother putting myself through the hard work and near insanity of a thesis, when there are no graduate jobs around here? In this way, social class has factored into where I stopped my formal education.

However there is a key difference between the experiences of Emily and me. She had no choice. I do. It's inclination based on class, not class itself, which halted me. I could move. I could save my money, do the work and live somewhere with appropriate employment prospects.

The limitations on Emily's opportunities were imposed, mine are self-imposed. Though there is a argument that the notion of relocating away from all I know and love is an indirect imposition.

I would instantly lose the support network of my extended family in the close vicinity. In 2013, the likelihood is that those with doctorates will be middle class, which could influence who I'd be living and working alongside. Seeing as I have a broad regional accent, I would probably have to change my diction, in order to be understood by my new neighbors.

These prospects are so unattractive, as to practically guarantee that I won't aspire to it. Yet that doesn't alter the fact that I could. Emily could not. That is the major difference between our situations.

Nevertheless Emily Wilding Davison and I gained our qualifications. One century apart, we each rode a tide of hopes and dreams straight to the job market. Yet she still ended up as a governess and I still ended up in an office.

When I was a little girl, there was a room in the local Working Men's Club which was male only.

When I was a little girl, there was a room in the local Working Men's Club which was male only.

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Comments

I honestly think it depends upon your social class and the amount of jobs out there. When the job market looks like it does at the moment (in Britain), then nepotism beats any piece of paper.

Do you think that having degrees is a barrier in some jobs, even to men?

It's a hard call to make. On the one hand, internalisation of the glass ceiling is definitely a factor. On the other, when that is recognised and you go for it, then it turns out that the glass ceiling is still there anyway.

But it's coming down. This definitely feels to me like a generational thing.

Thanks this is a really thought provoking article - I have a friend who gave up the opportunity of applying to ox-bridge for the same reasons you sited - i.e he thought he would be surrounded by middle class people with whom he would have little in common. The ironic thing is most of his mates are now 'middle class' anyway - as are all of his interests, what he reads, watches etc. Its a shame these thoughts put you both off aiming higher. I wonder if it could be seen as an internalisation of the glass ceiling?

I'm glad that you thought so. It was an interesting exercise to write. I just hope I did her justice.

An interesting comparison and great way to portray Emily Wilding Davison's life.

Mira - Thank you very much. As for your take on it, you're not being a spoil-sport at all.

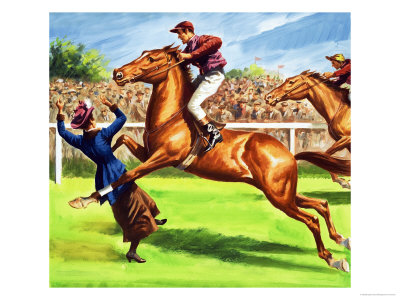

In fact, accepting your lot, and NOT throwing yourself under a galloping horse's hooves, is actually the sane option. But only if you can bear that without resentment and disappointment burning holes in your psyche and eroding your self-worth. Then you're merely switching the big, dramatic moment of insanity for a slow, creeping, long drawn out smothering kind of insanity.

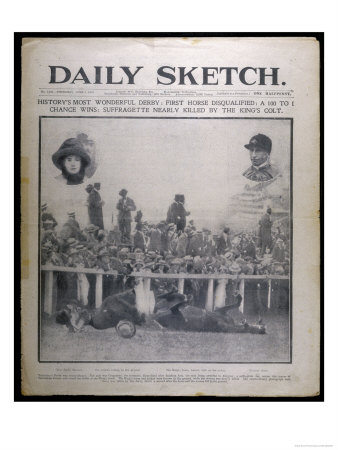

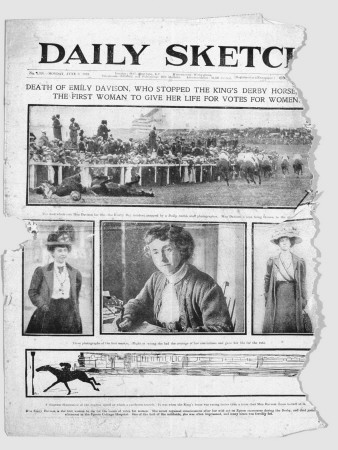

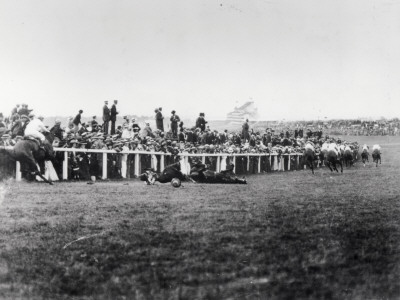

Emily found that the latter was worse than the former. She gave up her governess job, when she became more entrenched in her Suffragette activities, despite the fact that left her without a livelihood. The sane option bored and rankled her too much to accept it, so her choices became even more limited.

I think I straddle the ground between you and Emily Wilding Davison. I can empathize with what you said about lowering aspirations to what's achievable. I'm also at my happiest when running wild in nature, hippy Pagan creature that I am.

But I also took a very Emily-esque leap of faith, when I walked out of the job centre and lost my benefits, in order to not give up writing. That worked out ok for me. It didn't for Emily. I have more opportunities to test out than she ever did, which made the difference.

You and Emily share a perverse outlook though. She was subject to peer pressure which said, 'Do not aspire to anything. Never reach higher than you're given.' So she aspired to it all. You are told, 'Aspire! Be everything! Reach higher than ever before, then reach higher than that!' So you lower your aspirations. Rebel.

Catana - That works brilliantly, but only if the author is writing about their own class. Otherwise, they're making those nuances up as they go along.

If you're really interested in British class etiquette, then I totally recommend Kate Fox's book 'Watching the English'. It's not only informative, but hilarious and entertaining too. Also here's one I wrote earlier and on another site: http://suite101.com/a/tea-code-britis... Would you like a cup of tea?

I think you do your fellow American writers a disservice. Exhibit A: 'The Great Gatsby' for the upper echelons of society on the eve of the Great Depression; and Exhibit B: 'The Grapes of Wrath' for the lower orders during it.

Etiquette and other social behavior rules the former; while the progressive breaking down of the same, in the latter, symbolizes just how defeated these people became. (Before Rose of Sharon rewrites the rules to something more suited to surviving.)

Great article, Jo, and really interesting points in comments, too. I knew her story as I read about the suffragette movement at one point. I don't want to be a spoilsport, but I have come to think that sometimes life can be truly wonderful if you choose less education and come to enjoy simple things more fully. We've been conditioned to desire too much, I think, more than we can handle. I certainly find it difficult to follow so many new things happening in the world and think back to a time when I lived without a TV and spent more time in nature and with friends than with information. But that's just where I am in life on my particular journey. And no, I definitely wouldn't want women not to have choices! Each woman should decide for herself the kind of life she wants. I for one am trying to learn to desire less in terms of education and future jobs. I find that time in nature and relationships are much more important.

I love Henry James. :)

Yes, I can definitely see how that would be the case. The 'nouveau riche' have always been a 'problem' for the upper classes here too. That sort of money buys access into the kind of clubs and circles populated by the higher echelons.

What ensues is really a clash of cultures within the same country. It's discomfort that emerges as snobbery. The 'nouveau riche' will be inadvertently clattering through all manner of etiquette breaches. The old money people won't have a frame of reference to cope with that.

When it comes to the subtleties of the British class system, even the language to communicate appropriate behaviour doesn't exist.