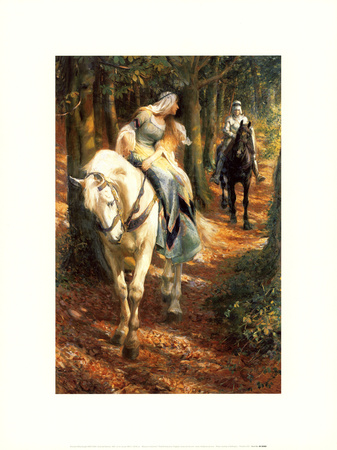

Part of the reason that Erec's actions become so untenable is because we've no longer got the thought processes behind them. He's been our guide through the story so far, but his subtle silencing gives us no choice but to latch onto the nearest point of empathy - Enide. Yet it's done in such a way as to trick us into thinking that we're still following Erec's story.

Enshrining the male viewpoint, as the desirable norm in story-telling, isn't something peculiar to the Medieval period. The Bechdel Test wouldn't exist in today's world, if movies didn't habitually side-line female characters. Chrétien's gender perspective switch would be radical if he was a Hollywood scriptwriter now, let alone entertaining a 12th century French court.

Life revolves around the heroine of a courtly love tale, but she's not supposed to participate in it. Enide and her ilk should frankly be interchangeable, not only with each other, but with a statue, or a plant-pot, or anything that our heroic knights can focus upon as they compete and fawn. The chivalric heroine could be a rock in a headdress, as long as it's pretty and pure enough.

From the second that she's placed on that horse, a flesh and blood Enide becomes an active part of the story. She gets dirty and bloodied. She falls ill under her emotions (until then a theme common only for male heroes), and the stress of her situations turns her pale. She gains a measure of control over her life, even if it's only to disobey a command to silence.

As the story goes on, we see her intelligence shining through. She evaluates the ideals of the courtly love heroine (keeping silent) against real world considerations (Erec could die), and finds the former wanting. She out-wits potential rapists and abductors. She refuses her consent in a forced marriage.

Yet all of this is disguised under the fact that Enide constantly reaffirms, mostly in thought, her belief in the idealism of female roles within the auspices of chivalry. Her actions belay her sentiments each time. But it's done so cleverly, that audiences would be cheering her on, even as she breaks every code of courtly love.

By the time we've followed Erec and Enide into the great hall of Count Limors, the subversion of the genre is no longer subtle. Limors literally yells into Enide's face all that she should attain to be or possess. He's reciting the staples of the Romance heroines - riches, a good marriage, unthinking consent, obedience, sitting on a dais and looking pretty - but we're all cheering Enide on as she resists them all.

Her victory comes not in compliance, but that almighty rebel yell that she sounds against Limors. Her defiance is loud enough to raise Erec from the dead, mustering the full force of his chivalry in defense of her choices. He trusts and falls in love with her all over again because of that moment.

Once back at King Arthur's court, Enide is again elevated to the status of venerated, pure and ideal heroine of the courtly Romances. But it's framed as something now earned. The praise of the court is all about that scream. In essence, she achieved perfect womanhood by rejecting all that the chivalric codes (and societal norms too) perceived as perfection for her gender.

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Comments

Yes, I went for a look and ended up writing a whole article about it!

Well, I'm excited for what your research turns up! :)

edit- I left this comment before I saw the new article. I'm going to check it out now!

Oh! Nice one! I'll go and check out your article forthwith, as I didn't know about any of this.

No, the gospel of Mary Magdalen is a gnostic gospel of very dubious provenance arising in the post apostolic age, [like all gnostic materials.] The part that I am thinking of is the Yahwist document, which was one of the four sources of the Pentateuch, which Friedman [writing in Who Wrote the Bible] thought came from a female source. To understand the Yahwist source think of four strands woven together [the Y, E, P and D sources] and then cut across to make the modern five books that you can see now if you open the Old Testament.

If you read my article on "scandalous women" you will see some of the material which led Friedman to think that a female story teller was behind part of the Old Testament.

There is a theory that Mary, Jesus' mother, was a source behind the Gospel of Luke, specifically the first two chapters, from 1:4 to the end of chapter 2.

Frank - We do know that Marie de France had her hand in it, but I'm not sure how much on this particular story.

I'm interested in the female authorship of a section of the Bible though! This is the Gospel of Mary Magdalen?

Ember - You've absolutely stunned me. In twenty years of researching (and general obsession) the Arthurian legends, I've never once heard any suggestion that Chrietien de Troyes was female. But you're right! We know so little about the author, that there's no reason to assume he's male!

The likelihood is there. Writers in the 12th century are almost always men. But note the 'almost'. Chrietien's own patron, Marie de Champagne, was a Medieval female writer.

There is much in Chrietien's writing that reveals a feminine point of view. That's been exclusively explained away as Marie's influence. In fact Chrietien says that point blank in the introduction to 'Lancelot'. Marie gave him the material and told him how to write it. Chrietien just put in the work, effort and imagination.

I see no argument just now that proves Chrietien's gender either way. Leave it with me. I'll see what I can dig up. But it's blown my mind that he could be a woman. Nice one!

As for the rest, it's astounding how Medieval literature raises issues about gender that are still so pertinent today, as evidenced by your Amish lady example. That's even more relevant than I think you know.

I didn't mention here how the French Romances subverted the Celtic notions of divine Sovereignty, from land to person. I do plan to write about that though, so I won't go into it here. Your Amish lady would totally fit within that theme.

It would be great if we could see some research on the influence of 'Erec et Enide', but I should imagine that it would be quite difficult. If only to tease out this particular impact from the wider courtly love/chivalry influence, and from there into general cultural trends amongst Medieval French aristocrats. Again leave it with me. Someone must have looked at it!

It is likely that story originated from a woman, as women were great story tellers. [There is a section of the Bible that might have come from a female story teller.] Chretien would have incorporated it into his work.

One final question. I'm aware that many women used to use a male pen-name to write/be published. I know all we have is the name (or title) Chrétien de Troyes... but do you think it was written by a woman? I know you used male pronouns, but it doesn't mean the possibility isn't there... and you may know for sure one way or the other so I thought I'd bring it up. It was just a thought that occurred to me.

I'll hold off on further questions/comments until you at least get a chance to reply. Sorry. :|

Okay, sorry multiple comments, I wasn't done babbling.

I think the story is interesting. I am curious to know what effect the story had on women who read it. I think it is something that we probably can't know, but I can just picture how it might have changed some women's perspective on their role in a relationship. Nothing drastic or huge. Just a small change in self image, perhaps one of many small things that collected over time leading up to women becoming more and more liberated. So perhaps it didn't have any profound effect immediately but I guess maybe it was one of a million little things that changed over time. To put it colloquially, I think that it's really cool.

Anyways, I agree that it probably wouldn't be a Hollywood blockbuster. I like your line at the end that it should be. But, part of me thinks that Hollywood would ruin it anyways. I am a ridiculously massive fan of the types of indie movies that make you feel really uncomfortable when you watch them, but if you can survive the whole movie, you find there's actually quite a bit to be gained from it. This sounds like it could be one of those movies. I could see it being appreciated by a lot of subcultures who took the time to look at it beyond what they're getting at the surface.

Also- I'm not quite sure how this all ties in with the Arthurian legends, though. That would be because I pretty much know next to nothing about them. (So you'll have to explain) I read the other set of articles you wrote which related to it (they were the ones on Y Ddraig Goch, yeah?) that were very interesting.

Okay, so please don't laugh... I was thinking about those articles the other day, and then asked my friend if she knew that Arthur and related legends were actual historical stories/ stories related to historical events etc. and not just a children's story. A legit "Did you know..?!" She was as shocked as I was, so at least there's that. But it is really interesting to me as a topic in general, at least the few that you've written and posted here so far. So, I think I said it when you wrote the others, but yeah, it is definitely something I'm interested in reading more of! :)

This was really interesting. I'm going off of your synopsis of the story because I've never read it, but I got the gist of it, and your analysis really got me thinking!

This almost entirely unrelated, but I watched bits and pieces of this show about Amish young adults who were offered a trip to NY if they agreed to be filmed for it. (So basically a reality TV show, just slightly less trashy I suppose). Anyways, the main reason I kept watching it was to find out what happened to one of the youngest. This one girl was interested because she thought it would be the most amazing thing to meet a man who would consider cooking for her or do some laundry. Arguably, the vast majority of the things she declared important to herself really don't fit in with modern ideas of feminism, but even with being raised in such a closed off community and limited exposure to the modern world, the ideas and seeds of feminism were there. She was easily the most conservative of the group, but I'd dubbed her the feminist, and because of that had someone comment that it was a bit silly to consider her an image of feminism. I said they needed to look again. Perhaps my favorite moment, from the start of the show where she talked about this dream she had of this imagined, impossible world where "men can do some women's work, and women can do men's work" and fast forward to when they've been in New York a couple of days and they go grocery shopping. When they were paying, amid all of the shock at the cost of things, availability of alcohol etc., she turns to one of the males in the group and asks why he didn't pick out any food for himself. He immediately replied that he was a man, and therefore it was not his job to worry about the food. (He is 100% serious.) She quips back something to the extent of 'it's not my job either, I hope you enjoy going hungry' (can't recall what she said verbatim). But my reaction was like 'HECK YEAH! She's so cool!!!'

Really, the only thing this relates to is when you were talking about why the context is so important. But it really is. Her telling a fellow Amish man she wasn't going to cook for him is far braver a move than what a lot of modern feminists do in their everyday lives who are properly considered feminist. (Not to down play it by any means, just...context!)