Alexander Hadfield was an Eyam man with a bright future. He had recently married the widowed Mary Cooper and become step-father to her two young boys.

Alexander Hadfield was an Eyam man with a bright future. He had recently married the widowed Mary Cooper and become step-father to her two young boys.

As a tailor, his trade was so brisk, that he'd been able to take on an assistant. George Viccars lodged with the family in their Church Street home.

It was he who took possession of the parcel from London. It had been carried on the back of an open cart for the final leg of its journey. In typical British summer fashion, it was raining. The cloth within arrived damp, so George's first job was to stretch it all out in front of the hearth to dry it off.

That was on September 3rd 1665. Four days later, he was dead.

The cloth had been infested with fleas. Half-starved from their incarceration in the package, they had feasted upon George Viccars. The fleas were carrying the same bubonic plague, which was currently devastating London.

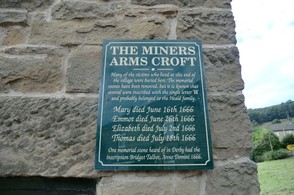

By the time it had finished its rampage through Eyam, only Mary would be left standing in that house. She would have lost not only her two boys, her husband and lodger, but another ten relatives besides.

Next door, Jane Hawkworth would bury her husband and baby son, alongside twenty-three more relations. On the other side of the Hadfield house, the entire Thorpe family were wiped out. All nine members of them.

They weren't alone.

Throughout Eyam people were dying, as the pestilence spread. From September 7th 1665 until November 1st 1666, the tiny population would be decimated. But most of them did not run.

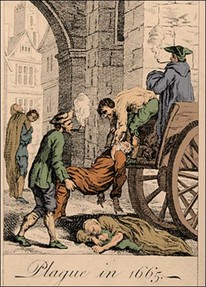

In London, the streets were awash with scenes of horror. Doors marked with thick, red crosses. Hollow-eyed people wracked with exhaustion and desperation. Death everywhere.

In London, the streets were awash with scenes of horror. Doors marked with thick, red crosses. Hollow-eyed people wracked with exhaustion and desperation. Death everywhere.

Alexander Hadfield was an Eyam man with a bright future. He had recently married the widowed Mary Cooper and become step-father to her two young boys.

Alexander Hadfield was an Eyam man with a bright future. He had recently married the widowed Mary Cooper and become step-father to her two young boys.

17th century Eyam was a God-fearing place. This was a Puritan strong-hold, though not everyone followed that faith. A large proportion were Anglicans instead.

17th century Eyam was a God-fearing place. This was a Puritan strong-hold, though not everyone followed that faith. A large proportion were Anglicans instead.

Keith Winter

on 09/27/2012

Keith Winter

on 09/27/2012

As well as asking the people to stay within the borders of Eyam, there were two other requirements.

As well as asking the people to stay within the borders of Eyam, there were two other requirements.

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Comments

A great article and it is spot on accurate. Thank you.

Eyam is one of my favourite places and I visit once a year as it is only 40 minutes or so drive away. Each year they hold the Derbyshire well dressings and they are definitely worth a visit if you get an opportunity to do so.

Eyam has a very spiritual feel to it as you walk around. Did you know that the descendants of Eyam plague survivors are immune to AIDS, something to do with their altered immune systems ?

So you could have had family there during the plague? If so, your family has my major respect.

Hi Jo - we have ancestry there but there was a gap of over 200 years between one lot moving out and the next lot moving in.

Do you have ancestry there, or family who moved to Eyam? Either way, it must be an amazing place to leave. Scenery alone would make it worth it, but that astounding history just ices the cakes.

Eyam is a place I've visited many times because I have family who have lived there for 30 years or more. Your article has revived so many old memories - thanks for sharing.

Welcome to Wizzley! You'll find a very friendly and encouraging bunch of people here.

Thank you for your kind words about my article. Having visited the village, it's hard not to become moved by their story. It was a terrible situation, but with a very courageous response.

I like to think that I'd have stayed, but as you said, we can't know unless we're ever in that situation.

Thank you very much. <3

Opps! forgot to subscribe. Bookmarked and shared.

You're very welcome. It's a fascinating place to visit as well, if you're ever in the area.

Fascinating, well written story. It's not often that I read a complete webpage, but this one had me completely transfixed. Thank you very much for sharing.