It would have been like the release of a new Apple product, or a talk on the future of Facebook now. An auditorium full of the great and the good, the press and other interested parties, all clamoring to see unveiled the latest in technology.

It would have been like the release of a new Apple product, or a talk on the future of Facebook now. An auditorium full of the great and the good, the press and other interested parties, all clamoring to see unveiled the latest in technology.

This was the scene on the afternoon of June 4th 1903, at the Royal Institution lecture. In front of a packed hall, Marconi had set up his equipment.

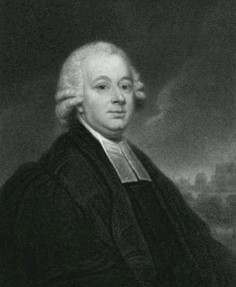

Wireless technology was so new that many were incredulous at the fact it could exist at all. Marconi had only made it work across the Atlantic a year previously! To bolster his case, he had a star witness, the respected Physicist John Ambrose Fleming standing alongside him.

The brass gleamed. The woodwork shone. The people watched and waited, while Marconi spoke from the lectern. He brought on Fleming, whose distinguished reputation added credibility to his claims. And then the apparatus sprang into life.

"Rats! Rats! Rats!" It spelled out in Morse Code to the shock of Marconi and Fleming, and the interest of the audience. Many of those understood the code very well. It wasn't the language that was being introduced here, but the method by which it was relayed.

For even those slow on the uptake, the expression of Marconi on the stage must have told the rest of the story. It was the equivalent of a mobile 'phone ringing at the wrong moment, then being answered on loudspeaker.

Fleming didn't react. He was deaf and therefore had no idea that anything untoward was happening. He continued to speak in support of Marconi and the system.

"There was a young fellow of Italy," tapped out Marconi's machine for all who would listen, "who diddled the public quite prettily." The limerick was completed in sentiments, which the only Edwardian witness to chronicle it described as en suite. That's toilet humor to me and you.

The transmissions slid off into quoting scathing tracts from Shakespeare, before ending in personal insults. This was all printed off on the recorder beside them.

For a man who'd claimed that his wireless technology was utterly secure for private messages, this was highly humiliating. Marconi had already been speaking for three quarters of an hour, and his focus had been on the security of his system and the privacy of messages transmitted upon it.

Guglielmo Marconi didn't invent the Morse Code, but he made it famous. It was his technology which allowed the language of dots and dashes to be transmitted over great distances.

Guglielmo Marconi didn't invent the Morse Code, but he made it famous. It was his technology which allowed the language of dots and dashes to be transmitted over great distances.

The Maskelyne family were very well known in the Age of Reason. They had been for generations.

The Maskelyne family were very well known in the Age of Reason. They had been for generations.

It would have been like the release of a new Apple product, or a talk on the future of Facebook now. An auditorium full of the great and the good, the press and other interested parties, all clamoring to see unveiled the latest in technology.

It would have been like the release of a new Apple product, or a talk on the future of Facebook now. An auditorium full of the great and the good, the press and other interested parties, all clamoring to see unveiled the latest in technology.

How did Maskelyne hack the Marconi system so completely and so publicly? It was easy. You could have done it.

How did Maskelyne hack the Marconi system so completely and so publicly? It was easy. You could have done it.

In theory, Marconi's channels could have been reasonably secure. At least until the hackers developed something with which to scan the frequencies.

In theory, Marconi's channels could have been reasonably secure. At least until the hackers developed something with which to scan the frequencies. The reaction from Fleming (pictured left) and Marconi was an early echo of the same accusations heard today by those targeted by movements like Anonymous.

The reaction from Fleming (pictured left) and Marconi was an early echo of the same accusations heard today by those targeted by movements like Anonymous.

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Comments

Thank you very much, Shaz! My friend and I were musing last night and we feel sure that somehow has to have hacked telegraphy in the 50-odd years before. We just don't know about it yet. It's my mission now to go and check. If we're right with our instinct, then Maskelyne will lose his crown as the first hacker.

Thanks for the thumbs up and plus one. :D

Such an interesting read. Very enlightening and surprising that hacking has been around for so long. Nice Wizz! Thumbs up and g+1 :)

Samsara - Indeed it is! Though I'm now sitting here with a mental challenge. I'm wondering if I could find an even earlier hacker. After all, we have all of those years of telegraphy to explore. Surely someone hacked that.

Spirit of RS - Maskelyne does seem very ahead of his time. That's why I couldn't resist all of the Lulzsec mentions, because this is precisely their modus operandi. It's certainly AntiSec, so I could have crow-barred Anonymous into there too.

Maskelyne was furious with Marconi, so to my mind there was a strong element of vengeance here. But Marconi was standing in the way of anyone developing anything similar, when he was himself standing on the shoulders of the same giants as everyone else. It was merely a case of who could get to the patent office fastest.

Marconi did go so much further though. He could see where this was all leading, so patented against everything he could see being a future invention/development.

I'm glad that you enjoyed reading it.

Thanks both for your comments.

I'm so glad that you got the joke! When I was looking to illustrate that part, I was covered in Edwardian images. I sorted through thinking, 'I need one that just says 'Like a Sir' and 'hacker' to illustrate both the action and the Edwardian etiquette...' Then I stopped and just burst out laughing.

I couldn't not use it then!

Very interesting. I think he was rather justified since calling Macaroni on his stuff proved that Macaroni was wrong.

I love the added irony in the use of the Lulzsec image that the image itself is sometimes referred to as the "Like a sir." image. XD