Gawain (one of Arthur's own chief advisors) and Edern ap Nudd (still representing the interconnected Underworld) attend Geraint, alongside a group of experienced chieftains or their heirs. Together they ensure that Geraint is accepted by his people, knows his territory and faces no immediate challenge to his leadership, then they depart.

All fired up, Geraint enthusiastically consolidates his position as ruler, then seems to get bored. Significantly, we're told that he gives up on holding tournaments, because there's no-one there who can provide a decent challenge.

He's patently still hankering for his old life back with Arthur.

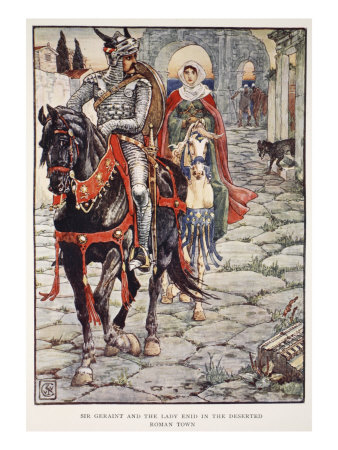

Geraint takes to hanging around with Enid, while neglecting his duties to his people. In short, his resentment at having to come home is such, that he considers his mere presence to constitute leadership. He does love his land, hence staying put, but as something abstract. It's not a soul connection worthy of his passion nor even his active participation.

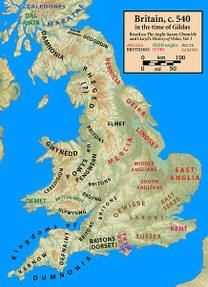

It's his father, the old ruler, who still truly cares about their territory and tribe. He's attentive enough to see the vulnerabilities opening up, and he turns to Enid - the Goddess of Sovereignty - for help. Her distress signals that a power struggle could usurp Geraint as reluctant ruler.

We're told that Geraint misunderstood Enid's cry to mean that she'd already been unfaithful, i.e. that she'd already switched her divine support in favor of another claimant. But his interpretation wasn't too wide of the mark.

Enid had pretty much just given him notice that his indifference had to end. He had to learn to love Dumnonia body AND soul, accepting her favor not in arrogance as his right, but as something to be cherished for its own sake. He had to live and breathe the place. The Dumnonii had to mean more to him than Arthur's people.

The Goddess of Sovereignty would always choose the strongest and the best candidate to favor as chieftain. Geraint was that, hence she supported him still. But from now on, it wasn't enough to merely rule. His connection to the land had to be absolute.

Geraint understood. If he didn't fight hard for something that he didn't particularly want, then he would lose it. What followed was the reluctant ruler on a spiritual journey of discovery to find out if he cared.

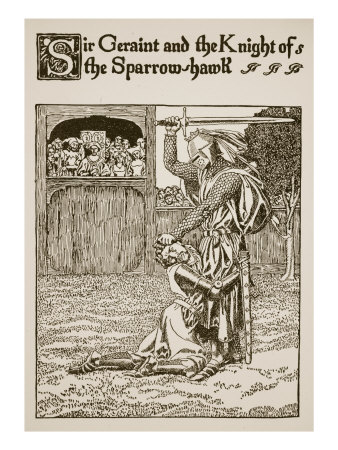

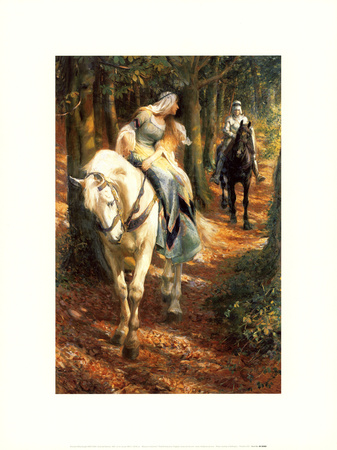

As prospective chieftain of his people, Geraint needed to gain Enid's approval and support in his claim of the territory.

As prospective chieftain of his people, Geraint needed to gain Enid's approval and support in his claim of the territory.

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Comments

My work here is well and truly done. :) Thank you for reading to the end.

That's the thing about these legends. They really are a mixture between real history, mythology and religious stories (most Pagan, some early Christianity, plenty of Medieval mysticism).

Yes, I did see that. And you know, after getting through it all, the ending really killed me. Not in a bad sense, but to have gone through all of that, and then it's like by the way... And then you ended it all with those last three lines. So before I could think of a place to go with it all I kind of just sat there like :C

See what I meant about no obvious places to split it into more articles?

You're asking a very Wiccan question there. It's usually framed as, 'all gods are one god, and all goddesses one goddess' - a phrase made famous by Marion Zimmer Bradley's 'The Mists of Avalon'. Some Pagans do believe it, others go with no, they're not all the same.

I've argued that question from both sides. But really I think the confusion comes in the difference between archetypes and individuals. In worldly terms, that's like wondering if you and I are the same, because we're both women. We could make a great argument that we are. But even better ones that we're not.

I meant that Enid was in the dark aspect of the Goddess of Sovereignty, as usually typified by Morrighan.

Knowing me means that sooner or later you get to know the Mabinogion too.

When you told me this was the longest article ever, and I said it didn't look that long... I was wrong, for the record.

Are goddesses with similar attributes but different names essentially the same goddess then? Or are they different. I guess here you were talking about Morrighan and said she is an Irish goddess, but then also said that Enid was Morrighan (or at least channeling her then?)

I recall you pointing out the Mabinogion to me in Wales, but I can't remember exactly what you said to me about it at the time. Funny how it's all coming back up now.