Alexander, Ted. “Antietam On Canvas: The Battle Art of James Hope.” Catoctin History, No. 1 (Fall 2002): 34 – 35.

Alexander, Ted. The Battle of Antietam: The Bloodiest Day. Civil War Sesquicentennial Series. Charleston SC: The History Press, 2011.

antietamguides. “Hope.” Antietam Battlefield Guides. September 19, 2012. Antietam Battlefield Guide Association. Blog. antietamguides.com. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- Available at: http://antietamguides.com/2012/09/19/hope/

Bailey, Ronald H. The Bloodiest Day: The Battle of Antietam. Alexandria VA: Time Life Books, 1984.

Flood, Peter. “James Hope.” Vermont in the Civil War > Units > 1st Brigade > Second Vermont Infantry > 2nd Vermont Infantry Biographies / Obituaries. Tom Ledoux & Associates. Web. vermontcivilwar.org. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- Available at: http://vermontcivilwar.org/units/2/obits.php?input=3072

Flood, Peter. “Hope, James.” Vermont in the Civil War > Cemetery Database > Virtual Cemetery. Tom Ledoux & Associates. Web. vermontcivilwar.org. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- Available at: http://vermontcivilwar.org/get.php?input=3072

Freeman, Larry. The Hope Paintings. Watkins Glen NY: Century House, 1961.

Hecht, William. “The Great Flood of 1935 in Watkins Glen: Images from July 8, 1935 in the Village of Watkins Glen, NY.” FingerLakes1.com Network > Features. FingerLakes1.com, Inc. Web. www.fingerlakes1.com. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.fingerlakes1.com/features/history-watkins-glen-1935-flood.php

Hays, Helen Ashe. The Antietam and Its Bridges: The Annals of an Historic Stream. With 17 photogravures from photographs by John C. Artz. New York and London: G.P. Putnam’s Sons / The Knickerbocker Press, 1910.

- Available via Internet Archive at: https://archive.org/details/antietamitsbridg00haysuoft

Henderson, John J., and Roger E. Belson. “James Hope (1818 – 1892).” White Mountain Art & Artists. Revised 2014-09-07. John J. Henderson. Web. www.whitemountainart.com. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.whitemountainart.com/Biographies/bio_jh.htm

Hennessy, John J. “An Artilleryman At Antietam.” HistoryNet > Civil War Times Magazine. December 14, 2012. Weider History Group. Web. www.historynet.com. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.historynet.com/an-artilleryman-at-antietam.htm

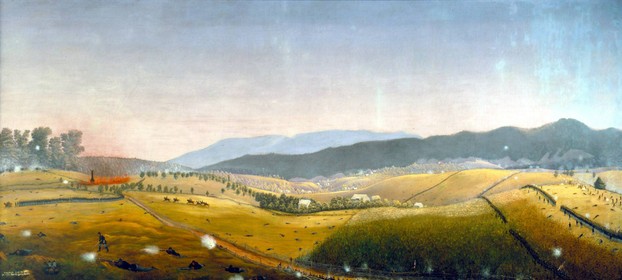

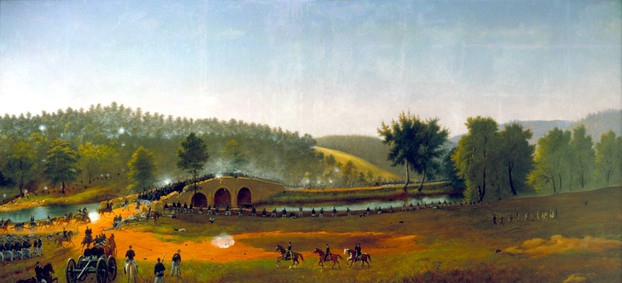

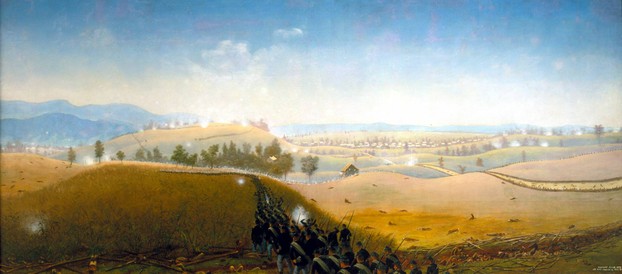

“Hope Paintings.” National Park Service > Antietam National Battlefield Maryland > Photos & Multimedia. National Park Service. Web. www.nps.gov. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.nps.gov/anti/photosmultimedia/hopepaintings.htm?eid=101853&root_aId=30

Irwin, Col. William H. "Report of Col. William H. Irwin, Forty-ninth Pennsylvania Infantry, commanding Third Brigade, of the battles of Crampton's Pass and Antietam." Shotgun's Home of the American Civil War > Civil War Battles > Antietam (Sharpsburg). September 22, 1862. CivilWarHome.com. Web. www.civilwarhome.com. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.civilwarhome.com/irwinantietamor.html

“James Hope.” Freedom and Unity > War and Industry 1860 – 1910 > Soldiers. Vermont Historical Society. Web. freedomandunity.org. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- Available at: http://freedomandunity.org/1800s/hope.html

Lewis, Ralph H. Museum Curatorship in the National Park Service 1904 – 1982. Washington DC: Department of the Interior, 1993.

- Available via Internet Archive at: https://archive.org/details/musuemcuratorshi00lewi

manwaringb. “Frowning Cliff, Watkins Glen, New York.” The Rockwell Insider. February 13, 2014. Beth Manwaring. Blog. rockwellmuseum.wordpress.com. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- Available at: http://rockwellmuseum.wordpress.com/2014/02/13/frowning-cliff-watkins-glen-new-york/

“McClellan on the field at Antietam.” Antietam on the Web. February 2, 2007. Brian Downey. Blog. behind.aotw.org. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- Available at: http://behind.aotw.org/2007/02/02/mcclellan-on-the-field-at-antietam/

Munsing, Stefan P. An Exhibit of American Painting, 1815 – 1865 from the M. and M. Karolik Collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. London: Trustees of Holburne of Menstrie Museum of Art and Bath Festival in co-operation with USIS American Embassy, 1900.

- Available via Internet Archive at: https://archive.org/details/exhibitofamerica00muns

Page, Priscilla. James Hope (1819 – 1892) Letters, 1853 – 1954. October 2000. Vermont Historical Society. Web. vermonthistory.org. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- Available at: https://vermonthistory.org/documents/findaid/hope.pdf.

Page, Priscilla. James Hope (1818/19 – 1892) Papers, 1854 – 1983 (bulk: 1856 – 1872). Vermont Historical society. Web. vermonthistory.org. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- Available at: https://vermonthistory.org/documents/findaid/hopePapers.pdf.

Priest, John Michael. Antietam: The Soldiers Battle. Shippensburg PA: White Mane Publishing Company, Inc., 1989.

Ross, Peter. The Scot in America. New York: The Raeburn Book Company, 1896.

- Available via Internet Archive at: https://archive.org/details/scotinameric00ross

Stevens, George T. Three Years in the Sixth Corps. A Concise Narrative of Events in the Army of the Potomac from 1861 to the Close of the Rebellion, April, 1865. Second Edition: Revised and corrected, with seven steel portraits and numerous word engravings. New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1870.

- Available via Internet Archive at: https://archive.org/details/threeyearsinsixt00stevuoft

Tilberg, Frederick. Antietam National Battlefield Site Maryland. Historical Handbook Series No. 31. Revised edition. Washington DC: National Park Service, 1961.

- Available via National Park Service at: http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/hh/31/hh31toc.htm

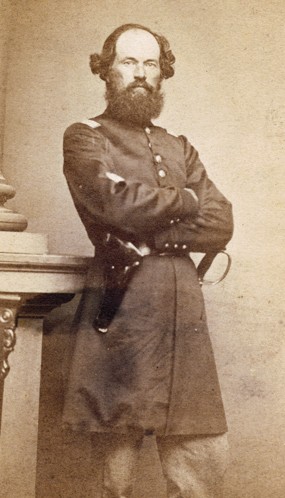

Victorian-Yankee. “Capt James Hope.” Find A Grave > Find A Grave Memorial# 20606375. July 24, 2007. Jim Tipton. Web. www.findagrave.com. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=20606375

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Comments