Armstrong, W.P. “Plant Fibers: Fibers for Paper, Cordage & Textiles.” Wayne’s Word: an On-Line Textbook of Natural History. March 5, 2010. (Last accessed May 18, 2011)

“Bowstring hemp Sansevieria hyacinthoides.” Plant Info & Images. University of Florida IFAS (Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences) Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. (Last accessed May 18, 2011)

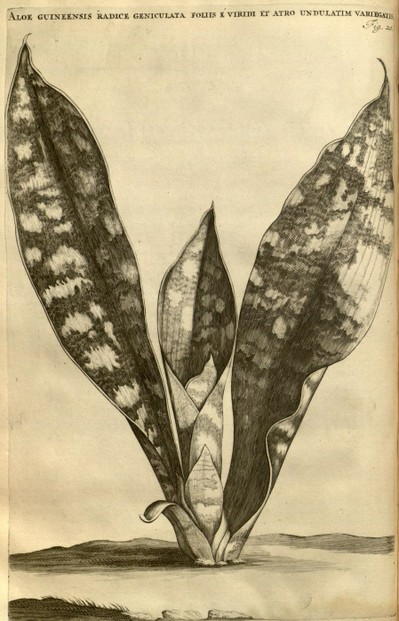

Commelini, Caspari. Horti Medici Amstelaedamensis Rariorum Plantarum Descriptio et Icones. Amsterdam: P. & J. Blaeu, MDCXCVII (1697).

- Available via Internet Archive at: http://the_bundle.archive.org/details/mobot31753000534963.

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/15229

Commelini, Caspari. Horti Medici Amstelaedamensis Rariorum Plantarum Descriptio et Icones. 2nd Part. Amsterdam: P. & J. Blaeu, MDCCI (1701).

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/ 15230

- Available via Internet Archive at: http://the_bundle.archive.org/ details/mobot31753000534971.

Commelini, Caspari. Praeludia Botanica ad Publicas Plantarum Exoticarum Demonstrationes, Dicta in Horto Medico. His Accedunt Plantarum Rariorum & Exoticarum, in Praeludiis Botanicis Recensitarum, Icones & Descriptiones. Lyon and Batavia: Fredericum Haringh, 1703.

Della Monica, Matteo; Domenico Galzerano; Sara Di Michele; Fabio Acquaviva; Giovanni Gregorio; Fortunato Lonardo; Francesca Sguazzo; Francesca Scarano; Diana Lama; and Gioacchino Scarano. "Science, Art, and Mistery in the Statues and in the Anatomical Machines of the Prince of Sansevero: The Masterpieces of the 'Sansevero Chapel'”. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, vol 161A, no. 11 (November 2013): 2920-2929.

- Available via Wiley Online Library at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ajmg.a.36258

Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds. 1993+. Flora of North America North of Mexico. 16+ vols. New York and Oxford. Volume 26 (2002), p. 415.

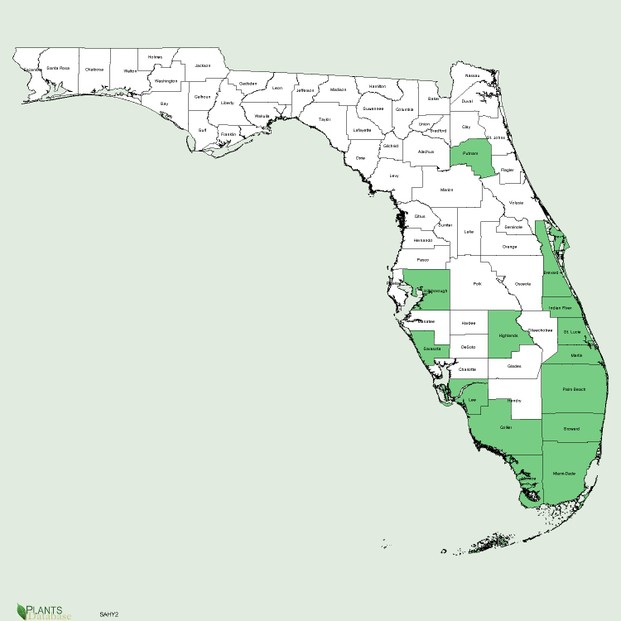

Gann, George D., Keith A. Bradley, Steve W. Woodmansee, and Janice A. Duquesnel. "Sansevieria hyacinthoides (L.) Druce Bowstring-hemp, Mother-in-laws tongue, Snake plant." Floristic Inventory of the Florida Keys Database Online. Delray Beach, Florida: Institute for Regional Conservation, 2007-2013.

- Available at: http://regionalconservation.org/ircs/database/plants/PlantPageFK.asp?TXCODE=Sanshyac

Gordon, Doria R., and Kevin P. Thomas. “Florida’s invasion by nonindigenous plants: history, screening, and regulation.” In: Daniel Simberloff, Don C. Schmitz, and Tom C. Brown, eds., Strangers in Paradise, pp. 21-37. Washington DC: Island Press, 1997.

Griffith, Lynn P. “Roots of a different kind --- how various foliage plants entered the United States trade.” Proceedings of the Florida State Horticultural Society, Volume 110 (1997): 104-107.

Hooker, Joseph Dalton (Sir). Curtis's Botanical Magazine. Vol. LIX of the Third Series (or Vol CXXIX of the Whole Work). London: Lovell Reeve & Co., Ltd., 1903.

- Available via Internet Archive at: http://archive.org/details/mobot31753002722475

Joyner, J. Frank, Edward O. Gangstad, and Charles C. Seale. “The vegetative propagation of Sansevieria.” Agronomy Journal 43: 128-130 (March 1951).

Kairo, Moses, Bibi Ali, Oliver Cheesman, Karen Haysom, and Sean Murphy (2003). Invasive Species Threats in the Caribbean Region. Report to the Nature Conservancy. Wallingford, UK: Centre for Agricultural Bioscience International (CABI), 2003.

Langeland, Kenneth A., Hillary Cherry, Cheryl McCormick, and K. Craddock Burks, ed. Identification and Biology of Non-Native Plants in Florida’s Natural Areas. Second Edition. Publication No. SP 257. Gainesville: University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants, 2008.

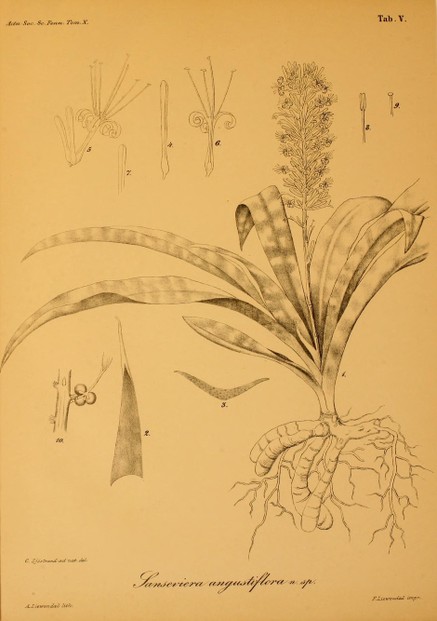

Lindberg, S.O. (Sextus Otto). "Sansevieria angustifolia." Acta Societatis Scientiarum Fennicae. Tomus X (pp 130-131). Helsingfors: Suomen Tiedeseura (Finnish Society of Sciences), MDCCCLXXV (1875).

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/ 52073

Macci, Fazio. Museo Cappella Sansevero. Naples IT: Museo Cappella Sansevero, 2006.

“Maritime Hammock Habitats.” The Indian River Lagoon Species Inventory. Smithsonian Marine Station at Fort Pierce, Florida. www.sms.si.edu (Last accessed May 18, 2011)

Redouté, P.J. (Pierre Joseph). Les Liliacées. Tome Sixième. Paris: l'Imprimerie de Didot Jeune, 1812.

- Available via Internet Archive at: http://archive.org/ details/mobot31753002806708

Richard, Amy, and Vic Ramey. Invasive and Non-Native Plants You Should Know, Recognition Cards. Publication No. SP 431. Gainesville: University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants, 2007.

Sansevero, Raimondo di Sangro. Lettera apologetica dell'Esercitato accademico della Crusca : contenente la difesa del libro intitolato Lettere d'una peruana per rispetto alla supposizione de'quipu scritta alla duchessa di S**** e dalla medesima fatta pubblicare. Napoli [Italy], MDCCL [1750].

- Available via Internet Archive @ https://archive.org/details/letteraapologeti00sans/page/n3/mode/2up

Scott, Chris. Endangered and Threatened Animals of Florida and their Habitats. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004.

Sultana, N., M.M. Rahman, S. Ahmed, S. Akter, M. M. Haque, S. Parveen and S. M. I. Moeiz. "Antimicrobial Compounds from the Rihzomes of Sansevieria hyacinthoides." Bangladesh Journal of Scientific and Industrial Research (BCSIR) (2011), 46(3), 329-332.

- Available via Bangladesh Journals Online at: http://www.banglajol.info/index.php/ BJSIR/ article/ view/ 9038

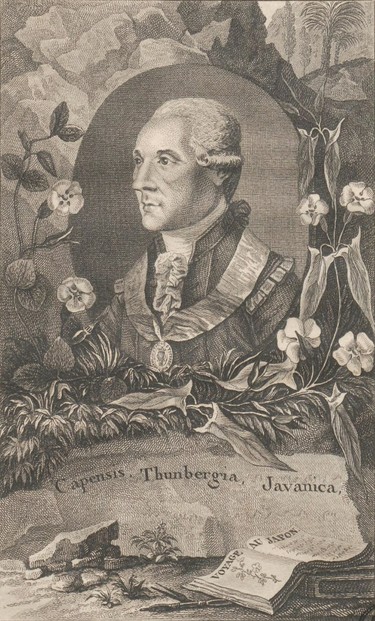

Takawira-Nyenya, R., and B. Stedje. "Ethnobotanical studies in the genus Sansevieria Thunb. (Asparagaceae) in Zimbabwe." Ethnobotany Research & Applications (2011) 9: 421-443.

- Available at: http://lib-ojs3.lib.sfu.ca:8114/index.php/era/article/viewFile/657/397

van Jaarsveld, Ernst. “The Sansevieria species of South Africa and Namibia.” Aloe 31: 11-15 (1994).

Varnham, Karen. “Non-native species in UK Overseas Territories: A Review.” JNCC Report 372. Peterborough, UK: Joint Nature Conservation Committee, 2006.

Whitney, William Dwight. The Century Dictionary: An Encyclopedia Lexicon of the English Language. New York: Century Company, 1911.

Wijnands, D.O. The Botany of the Commelins: A Taxonomical, Nomenclatural, and Historical Account of the Plants Depicted in the Moninckx Atlas and in the Four Books by Jan and Casper Commelin on the Plants in the Hortus Medicus Amstelodamensis, Rotterdam. Rotterdam: A.A. Balkema, 1983.

Wijnands, D. Onno. “The Hortus Medicus Amstelodamensis --- its role in shaping taxonomy and horticulture.” Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, Volume 4, Issue 2 (May 1987): 78-91.

Wijnands, D. Onno. “Nomenclatural aspects of the plants pictured by Jan and Caspar Commelin with three proposals to conserve or reject.” Taxon, Volume 34, No. 2 (May 1985): 785-787.

Wijnands, D.O. “Typification and nomenclature of two species of Sansevieria (Agavaceae).” Taxon, Volume 22, No. 1 (February 1973): 109-114.

Wilson, F. Douglas, Charles C. Seale, James B. Pate and J. Frank Joyner. “Sansevieria for ornamental use.” Florida State Horticultural Society Proceedings, Volume 70 (1957): 354-359.

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Comments