However, Lettie was already in his house and garden, albeit part of his children's gaggle of friends, and he'd already spotted her two years previously. Then he'd been impressed that she could read poetry AND spin a hoop at the same time.

Across the road, Mrs Catherine Landon discovered how much money there was in poetry, as long as it could be published in something like the London Literary Gazette. She casually mentioned to her new neighbor that her Lettie wrote verse. Might he have a look?

Jerdan made all of the right noises, but didn't exactly rush to acquire any samples to read.

Also in the Landon household was Lettie's paternal cousin, another Elizabeth Landon. The young lady acted as a companion for her aunt, while also a governess for the children. She penned two letters, a few days apart, building upon the promise made to Catherine that Jerdan really would look at the poetry. Elizabeth included some, just to make sure that they were in his possession.

Perhaps realizing that his neighbors could not be brushed off as easily as random people in the street, Jerdan did indeed respond this time. He wrote that there was potential in the verses, and some flashes of genius. But didn't exactly offer to publish any.

In truth - as he later admitted - he thought that Elizabeth Landon was the author. She was nearly thirty, so the poetry might appear a little juvenile from her pen. By now, Lettie was sixteen years old. Pretending that she was the poetess made it cute, and a selling point for his publication.

A short while later, Jerdan perceived an opportunity to expose their ploy. He was in a carriage, crossing London, with Lettie Landon as one of his passengers. As they passed St George's Hospital, he blithely commented that he would love to see a poem about it.

They stopped for dinner, no doubt with the publisher inwardly smiling about his little test. His smugness was soon frozen into shock. Lettie appeared at his side, as he finished his dessert, and slipped some pages onto his plate.

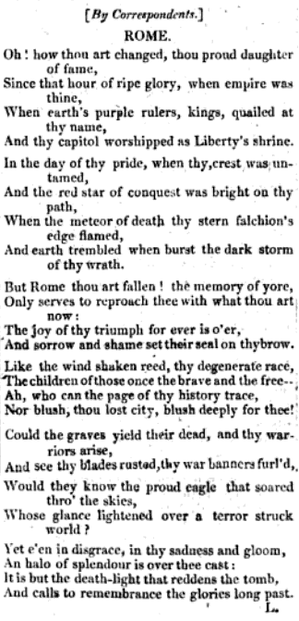

She'd written 74 lines of poetry about St George's Hospital, in the time it had taken Jerdan to dine, and it most certainly contained 'flashes of genius'.

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Comments

Ember - The best way to 'get' poetry is to read it aloud and let your emotions analyze it for you. Breaking down the structure and word form is something to be done in English Lit. classes, not in general reading. Poetry has always been best read from the heart, not the mind.

There's no evidence that L.E.L. was 'bored' in her writing about love. Though there was obviously profit in it. She defended it to the hilt, but then, she had to. We can't really know what her private thoughts were on it. And yes, I agree that real poets shed bits of soul into the verse.

Thanks for reading it. <3

Mira - Lots of things that we can identify with there, considering that we're both trying to make a living in precisely the same way. I wonder if L.E.L would have been on Wizzley, if she'd been alive today.

Yep, she seriously did go for it!

The final part is close to completion. Unless I get seriously side-tracked, it'll turn up today.

I genuinely wish that I understood poetry better. When it comes to connecting with literary arts there is something I just (and always have) lacked. It's not that I haven't been captured by the sentimentality or emotionality that many poems convey but I feel that is largely in part because poetry is such a huge part of one of my best friends life and I dedicated a lot of time to...I suppose 'understanding' it.

I think even if a genius poet is confined to writing about romance and love, if she is able to convey so much, capture so well, regardless of the topic she must've been an absolutely brilliant poet, but that's coming from someone who doesn't quite 'get' most of it until I'm guided through it, or left to mull over it for a while (a while as in, for example, the two plus years it really took me to connect to Fuel to the Flame that you shared with me, for example. I've definitely connected with but it sure took some time). I suppose there's the academic level, where academically I can understand, but poetry captures so much emotionality, it really needs to be something that is also happening on a spiritual level, that's what I think. I think poets really do share bits of their souls.

I'm sorry, I'm not sure everything I'm trying to say is making any sense. I've only quickly read this. I'll be back after I've given it a more solid read.

Yes, do continue. You mentioned three children. I wondered about that. Great page! I love your writing style, and her story is very interesting: all that work for The Literary Gazette, the way she turned poetry into a lucrative venture, her seventeen (!!) books of poems . . . I mean, this is serious stuff.

Loved this bit too: "Was she young? Was she pretty? And—for there were some embryo fortune-hunters among us—was she rich?" Ha ha