St Gildas mentioned wolves before. When he hurtled through the history of Britain, he referred to the Saxons as being invited 'like wolves into the sheepfold', then later described more 'wolf-cubs' coming to join them.

Maelgwn could technically have been persuaded by Saxons to leave his monastery, but it seems highly unlikely. Particularly when Gildas's earlier references weren't about the standards of any Saxon leader. It was more allegoric. The Pagans were loose amongst the lambs of God.

Gildas also discussed the legend of Britain's foremost Christian martyr St Alban. After the saint performed a miracle en route to his death, his executioner was struck with awe and converted to Christianity. Or, as Gildas put it, 'from a wolf became a lamb'.

It seems to me that, in Gildas's parlance, 'wolf' means Paganism and 'lamb' signifies Christianity.

With this symbolism in mind, it's quite easy to read what the saint is saying about Maelgwn here:

'...who of a wolf wast now become a lamb... out of the fold of our Lord, and made thee of a lamb, a wolf like unto himself, again?'

Maelgwn had been decidedly Pagan. He converted to Christianity, became a monk, then was converted back into Paganism. So there was the wolf, what about the eagle?

Gildas only referred to eagles on one other occasion. Also in his historical section, he had been describing attacks upon the British by Picts and Scotti. Suddenly he switched to a discussion of invaders from beyond the sea - which could possibly still be the Scotti, as they originated in Ireland. They would later over-run Alba renaming it Scotland. These were dismissed merely as 'wolves', who took plunder home, while leaving ruined lives, settlements and crops behind.

Envoys from Britain met with representatives from the recently departed Roman Empire. A legion was sent to help the British, supported by mariners and cavalry. It only happened once, but the Romans won the day. Their cavalry was 'like a flight of eagles'.

That's it. That's the mention. But the context is all wrong. Those eagles had 'compassion' and 'human nature'. Maelgwn's eagle is a monster and a castaway. No more clues in Gildas then.

Fortunately Welsh legend provides us with both an eagle and a wolf as castaways, and they were deposited just up the road.

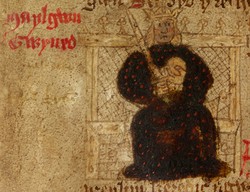

On The Ruin of Britain is the foremost historical document detailing Maelgwn Gwynedd's life, therefore it's worth dissecting precisely what the saint said.

On The Ruin of Britain is the foremost historical document detailing Maelgwn Gwynedd's life, therefore it's worth dissecting precisely what the saint said.

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Comments

I think I've ended every single Maelgwn article so far with the next one will be the final installment. Then I find more and more stories about him. That's the upside of bringing so many bards into your court, they all write songs name-checking you!

Eh, hem "In the fifth and final part of this Maelgwn Gwynedd series" ... Is this a 'for now' sort of thing, or am I meant to believe you here? :| (And also not including the relating side articles). Anyways, am excited for it!

Do I get a prize? :)

Three times: so your karma is paid up!

I reckon those of us who've read Gildas from start to finish most definitely deserve the harp music. I read him for Uni back in the early 90s and promised I'd never do that to myself again. I've read him start to finish THREE TIMES for these articles. Wizzley is absolutely not paying me enough for that.

You can have an exemption. Anyone who's already been there don't need to trigger their trauma again. Enjoy the music!

I have a collection of cds of Celtic harp music, [mainly Scots and Irish] but now you have shown me some that I have not heard before, so thanks.The harp is my favourite instrument, as you might have guessed. I know that you want Christians to read [suffer] Gildas ere they listen to the cds, but I've been suffering him for years, so do I get an exemption?