Maelgwn wasn't automatically the ruler upon his father's demise. Celtic society didn't work like that. The chieftain was the strongest person for the position, though in reality that tended to be the son - or a relative - of his predecessor.

Nevertheless, Maelgwn couldn't legally rule as an avowed monk. Then again, who was going to stand in the way of this military leader of proven prowess? As soon as Maelgwn renounced his monastic oath, we can be certain that it was game over for any other erstwhile chieftains.

Cadwallon had established the llys of Gwynedd in Aberffraw, on Ynys Mon. But Maelgwn disdained that for the fortress in which he was (probably) born - Deganwy. It dominated the entrance to the Conwy sea-port, but on the other side of the river. In short, Maelgwn made his base just over the border in Rhos.

This was the eastern territory of the Votadini ruled not by Maelgwn, but his uncle Owain Ddantwyn, then his cousin Cuneglas. From the very start, it seemed, the Gwynedd ruler was determined to become overlord of his great-grandfather's entire realm - Rhos and Gwynedd together. Lands which covered the whole of North Wales, taking in Chester too, all the way to the east. Curtailed at Ceredigion and Powys in the south.

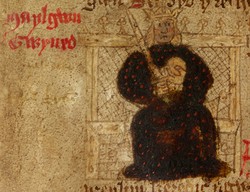

In doing so, Maelgwn would become probably the most powerful Celtic chieftain in Britain. His prominence, and that of his territory, would append the suffix Gwynedd to his name. Even the Saxons would refer to him as 'the Great'.

And to signify his elevation, he took the title Pendragon and the symbol of a dragon became his emblem. Some historians relate it to the last banner of the local Roman legions, who had abandoned Gwynedd a century before. Others to the Celtic legend of a red dragon uniting the Britons. Arthurian scholars see it as a borrowing, taking on Arthur's position in the wake of Camlan. It may be all of the above.

Maelgwn Gwynedd's dragon would eventually evolve into Y Ddraig Goch, the icon of the Welsh.

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Comments

That works for Pagans too, at least in my experience. I guess it all boils down to respect between religions, and within the marriage too.

I did once have a Sikh friend, who was legally married but unable to live with her husband. They were 'only' married in a registry office to get the lawful part out of the way, but the wedding in a Sikh Temple wasn't booked until a year hence. From their point of view (and family, friends etc) they weren't married at all yet!

It is worth noting that most Christian groups regard non-Christian marriages as genuine marriages and binding on the couple [the Mormons disagree and think that only marriage in a Mormon temple is true.] Thus a pagan handfasting is just as binding as a Christian marriage; and infidelity just as wrong.

Sorry, Frank, you were typing your comment as I was mine, hence we've crossed over.

I agree with the 'harem' thing. It was pretty much a status symbol for men to take many partners. You only have to look at the early Arthurian legends, where Arthur's many 'romantic' conquests have been clumsily air-brushed out by the 12th century writers. Or cross over into Ireland, where Cuchulainn's were left in.

Maelgwn's son Rhun Hir Gwynedd had a huge reputation for seducing every woman he fancied. Maelgwn himself attracted that legend about fathering children on the Pictish 'princess'.

It's not just the men too, though the women I can mention are either Goddesses of Sovereignty (famously promiscuous, as it was the nature of their 'job' to ritually mate with each successive chieftain of the land), or those subject to slander by Romans or Medieval priests. I'm thinking Gwenhwyfar or Maeve of Connaught for the deities, and Boudicca in history.

As for the Saxons, it comes down to which ones? Not all tribes left. Earthworks were thrown up to protect lands in the south and east of what's now England. Those Angle, Saxon and Jutes tribes holding them weren't going anywhere.

But Badon included a lot of Saxons only recently arrived, without any major foothold already, who were hoping to take territory from the Celts in the West Country. They were killed in droves and/or left afterwards. These were the ones who turned up on continental coastlines, where the Franks were busy fighting to expand their territories. Those homeless Saxons made ideal mercenaries for the time being.

Then, once the Frankish conquering was done, some settled there. But it wasn't a fabulous prospect for those Saxons looking for their own, self-governing land. The Franks were a bit too strong. That's when Justinian started throwing his wealth about, and boatloads of Saxons (presumably the sons and grandsons of those at Badon) returned to Britain.

I agree that Pictish and Brythonic Celtic were distinctly separate languages. But there's so much back and forth between the Lothian and Orkney Picts, and the tribes all over Wales, that there had to be common linguistic ground. Or translators working overtime. When Cunedda came to Gwynedd, he seemed to have no trouble communicating with the Decaengil. Though I shouldn't imagine the latter really wanted to hear what he had to say.

Yes, it was, but not like this.

It was the norm to have large families, not least because any contraception was herbal. For example, Gildas was one of fifteen surviving children. Those who died in infancy weren't recorded. One in ten women died in childbirth. That was the risk taken every time they gave birth. The widower would then be anxious to remarry as quickly as possible, so someone would see to his kids.

Mind you, it happened the other way around too. In violent times, men are prone to die in battle not to mention while defending their settlements from invaders (frequent in the 6th century). There were also the trillion other accidents or illnesses that would prove fatal. Widows were just as keen to acquire a new husband to provide for her family.

But what marriage meant (and gender roles within it) depended greatly upon the tribe in question.

We're still several centuries away from the Christian church embracing marriage as an institution which fell under its remit. In general terms, Celtic weddings were just as legitimate if performed outside a church - greenwood marriages with only the couple present, or handfastings with or without witnesses - as they were with a priest officiating. But only if all due consent has been obtained (not all people were free to marry without their guardian or chieftain's say-so) and the union was publicly announced. Recognition, insofar as I can tell, conferred legitimacy.

However, it was then a binding contract between the couple. No-one could legally tear them asunder, just like with modern marriages. Maelgwn and Sannan were not at liberty to have an affair, and they certainly weren't supposed to kill their spouses. But Maelgwn was the highest authority in the land. Other than aggrieved parties raising a warband to depose/kill him, or turning to the clergy to apply some serious emotional blackmail, there was nothing much else that anyone could do about it.

Other than, perhaps, ignore their ensuing marriage when announced, thus robbing it of any legitimacy. But that would have been horrifically risky, when Maelgwn could respond to your silence with his sword.

You might not have heard of the Picts, but you've seen one. Mel Gibson in 'Braveheart' was pretty much dressed up as one, only about seven centuries out of date.

Powerful men, Ember, tend to have harems including as many women as they can get. Kings have generally had harems. Even in historical times, polygamy of this kind was known.For example, Harold Godwinson had two wives, as did Macbeth. Macleod of Dunvegan in the sixteenth century had three wives and three mistresses in the same house. The women did not complain. It was not safe to complain about Macleod, especially in his hearing.

I am doubtful, though, about the idea that the Saxons were paid to come back to Britain by Justinian. Saxons settled here because they needed land, and so while going back might have been an option for mercenaries, others had made England their home, so there was no place in Germany to which many could return. By the end of the Roman period Saxons were here to stay.

Was Pictish mutually intelligible with Welsh? Well, Cumbric, spoken in Northern England and Southern Scotland was so close to Welsh that Bede did not distinguish the two. But Bede did say that the languages of Britain were Welsh, English, Gaelic and Pictish. He did not distinguish between varieties of English [Saxon and Angle] and Welsh/Cumbric, but he saw Pictsh as different from the others.

Was it normal for men in this time to marry multiple women like this?

I am not a historian, obviously, but this was the first time I'd heard of the Picts.