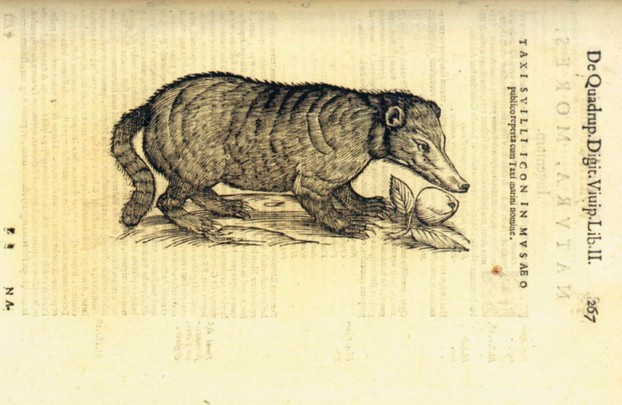

Aldrovandi, Ulyssis. Philosophi et Medici Bononiensis. De Quadrupedibus Digitatis Viviparis. Liber Secundus. Bonon [Bologna]: Apud Nicolaum Tebaldinum [Nicolai Tebaldini], MDCXXXXV [1645].

- Available via Wellcome Collection at: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/dhj55n53/items?canvas=203

ARKive. (2010). Nasuella olivacea in Ecuador. Retrieved on December 31, 2013.

- Available at: http://www.arkive.org/mountain-coati/nasuella-olivacea/image-G104223.html

Bisby F.A., Y.R. Roskov, T.M. Orrell, D. Nicolson, L.E. Paglinawan, N. Bailly, P.M. Kirk, T. Bourgoin, G. Baillargeon, D. Ouvrard. (eds.) (2011). "Nasuella." Species 2000 & ITIS Catalogue of Life: 2011 Annual Checklist. Retrieved on December 31, 2013.

- Available at: http://www.catalogueoflife.org/annual-checklist/2011/search/all/key/nasuella+olivacea/match/1

Clinton, President Bill. "I Still Believe in a Place Called Hope." Democratic Underground.com. Retrieved on December 31, 2013.

- Available at: http://www.democraticunderground.com/speeches/clinton.html

Damiesela. Los Mapaches, Olingos y Coatíes. El Coatí Andino, Nasuella olivacea. Retrieved on December 31, 2013.

- Available at: http://www.damisela.com/zoo/mam/carnivora/procyonidae/olivacea/index.htm

Eisenberg J.E. (1989). Mammals of the Neotropics. Volume 1: The Northern Neotropics. University of Chicago Press.

Eisenberg J.F. and K.H. Redford. (1999). Mammals of the Neotropics. Volume 3: The Central Neotropics. University of Chicago Press.

Frati, Ludovico. "Aldrovandi Tasso marino. Mountain coati, Tavole di Animali VI, 87r bottom (Nasuella olivacea)." Page 227. Catalogo dei manoscritti di Ulisse Aldrovandi. Con la collaborazione di Alessandro Ghigi e Albano Sorbelli. Bologna [Italy]: Nicola Zanichelli, MCMVII [1907].

Frati, Ludovico. Catalogo dei manoscritti di Ulisse Aldrovandi. Con la collaborazione di Alessandro Ghigi e Albano Sorbelli. Bologna [Italy]: Nicola Zanichelli, MCMVII [1907].

- Available via classic Google Books at: https://books.google.com/books?id=l1A0AQAAMAAJ

- Available via new Google Books at: https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/l1A0AQAAMAAJ

Helgen K. M., R. Kays, L.E. Helgen, M.T.N. Tsuchiya-Jerep, C.M. Pinto, K.P. Koepfli, J.E. Maldonado. (August 2009). "Taxonomic boundaries and geographic distributions revealed by an integrative systematic overview of the mountain coatis, Nasuella (Carnivora: Procyonidae)." Small Carnivore Conservation 41:65-74. Retrieved on December 31, 2013.

- Available at: http://www.smallcarnivoreconservation.org/sccwiki/images/1/14/SCC41_Helgen_et_al_2009.pdf

Hogue T. (2003). "Nasuella olivacea mountain coati" (On-line). Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved on December 31, 2013..

- Available at: http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Nasuella_olivacea/

Kaufmann, Thomas DaCosta. "51. Biblioteca Universitaria Bologna, Fondo Aldrovandi Tavole di animali VI, fol. 87r. The coati is described as a tassus marinus in Ulisses Aldrovandi, De quadrupedibus digitatis viviparis libri tres et de qudrupedibus [sic] digitatis oviparis libri duo, ed. B. Ambrosinus, Bologna, 1637, p. 267. . . .” Page 269. Arcimboldo: Visual Jokes, Natural History, and Still-Life Painting. Chicago [IL] and London [UK]: The University of Chicago Press, 2009..

- Available via classic Google Books at: https://books.google.com/books?id=sRuI5laxCZIC&pg=PA269

Kaufmann, Thomas DaCosta. Arcimboldo: Visual Jokes, Natural History, and Still-Life Painting. Chicago [IL] and London [UK]: The University of Chicago Press, 2009..

- Available via classic Google Books at: https://books.google.com/books?id=sRuI5laxCZIC

- Available via new Google Books at: https://www.google.com/books/edition/Arcimboldo/sRuI5laxCZIC

Mountain coati. The Animal Files.com. Retrieved on December 31, 2013..

- Available at: http://www.theanimalfiles.com/mammals/carnivores/coati_mountain.html

"Nasuella olivacea." In: Santiago Burneo (ed.). Mamíferos de Ecuador. Quito: Museo de Zoología, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador. Version 2013.0. Retrieved on December 31, 2013..

- Available at: http://zoologia.puce.edu.ec/vertebrados/mamiferos/FichaEspecie.aspx?Id=1858

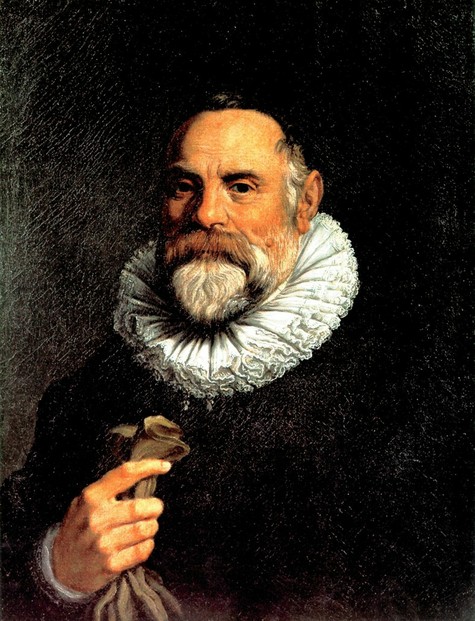

Posner, Donald. "Carracci, Agostino." Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 20 (1977).

- Available via Treccani at: https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/agostino-carracci_(Dizionario-Biografico)/

Procyonidae. Wild Forests.com. Retrieved on December 31, 2013..

- Available at: http://wiki.wildforests.co/topic/Procyonidae

Reid F. & K. Helgen. (2008). Nasuella olivacea mountain coati. In: IUCN 2013. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. Retrieved on December 31, 2013..

- Available at: www.iucnredlist.org

Rodríguez-Bolaños A., P. Sánchez. (2000). "Trophic characteristics in social groups of the Mountain coati, Nasuella olivacea (Carnivora: Procyonidae). Small Carnivore Conservation 23:1-6.

Rodríguez-Bolaños, A., P. S·nchez. 2000. Trophic characteristics in social groups of the Mountain coati, *Nasuella olivacea* (Carnivora: Procyonidae). Small Carnivore Conservation, October 2000 Vol. 23: 1-6.

Rodríguez-Bolaños, A., P. S·nchez. 2000. Trophic characteristics in social groups of the Mountain coati, *Nasuella olivacea* (Carnivora: Procyonidae). Small Carnivore Conservation, October 2000 Vol. 23: 1-6.

Rodríguez-Bolaños, A., P. S·nchez. 2000. Trophic characteristics in social groups of the Mountain coati, *Nasuella olivacea* (Carnivora: Procyonidae). Small Carnivore Conservation, October 2000 Vol. 23: 1-6

WildlifeExtra. (September 2010). First ever Mountain coati in captivity in Colombia. Retrieved on December 31, 2013..

- Available at: http://www.wildlifeextra.com/go/news/mountain-coati.html#cr

Wilson D.E. and D.M. Reeder. (2005). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. 3rd edition. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Comments

VioletteRose, Mountain coatis sometimes seem to get lost in the shuffle, especially through misidentification for their more familiar relatives.

They are indeed interesting.

Interesting, I never knew about this animal.