"An Age Entry for Nasua narica." The Human Aging Genomic Resources: online databases and tools for biogerontologists. genomics.senescence.info. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Available at: http://genomics.senescence.info/species/entry.php?species=Nasua_narica

Bateman T.. (2008). The Frog with the Big Mouth. Albert Whitman & Co.

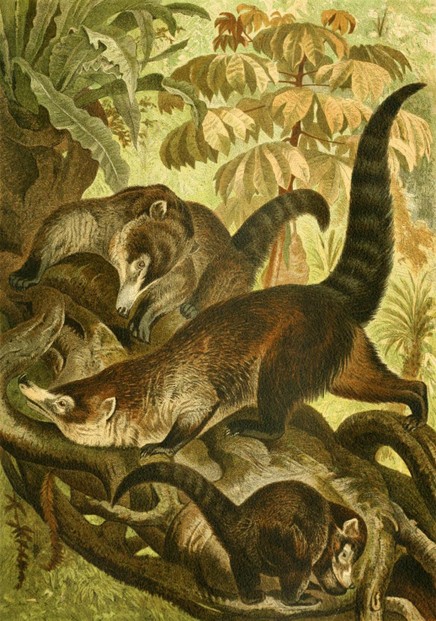

Brehm, Alfred Edmund. (1900). Brehms Tierleben; allgemeine kunde des thierreichs. Mit 1910 abbildungen im text, 11 karten und 180 tafeln in farbendruck und holzschnitt. Volume 2: Säugetiere. Leipzig and Wien (Vienna): Bibliographisches Institute.

- Available via Internet Archive at: https://archive.org/details/brehmstierlebena002breh

Burn B. (1984). North American Mammals. Bonanza Books: The National Audubon Society Collection Nature Series.

Burt W.H. (1980). A Field Guide to the Mammals. 3rd edition. Houghton Mifflin Co: Peterson Field Guide Series.

"Coati." en.wikipedia.org. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coati

"Coati (Nasua narica)." Pima Community College: Desert Ecology of Tucson A2. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Available at: http://wc.pima.edu/Bfiero/tucsonecology/animals/mamm_coat.htm

Decker D.M. (1991). "Systematics of The Coatis, Genus Nasua (Mammalia, Procyonidae)." Proceedings of The Biological Society of Washington 104:370-386. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Available at: http://biostor.org/cache/pdf/f8/c6/d7/f8c6d73ff3bab3dea9652afe0bb9b25f.pdf

Eisenberg J.F. (1989). Mammals of the Neotropics. Volume 1: The Northern Neotropics. University of Chicago Press.

Eisenberg, J.F. and K.H. Redford. (1999). Mammals of the Neotropics. Volume 3: The Central Neotropics. University of Chicago Press.

Perry S. and L. Rose. (1994). “Begging and Transfer of Coati Meat by White-faced Capuchin Monkeys, Cebus capucinus. Primates 35(4):409-415. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Available at: http://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/41610/10329_2006_Article_BF02381950.pdf;jsessionid=56D5926724D75CA5D0096FC1BDBBD022?sequence=1

"First Ever Mountain Coati in Captivity in Colombia." Wildlife Extra News, September 2010. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Available at: http://www.wildlifeextra.com/go/news/mountain-coati.html#cr

Gomper M.E. (23 June 1995). "Nasua narica." Mammalian Species 487:1-10. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Available at: http://www.science.smith.edu/departments/Biology/VHAYSSEN/msi/pdf/i0076-3519-487-01-0001.pdf

Grant S. (2006). "Coatimundi (coati) (Nasua sp.)." Exotic DVM 8(6):22. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Available at: http://www.ivis.org/journals/exoticdvm/8-6/Coatimundi.pdf

Guzman-Lenis A.R. (2004). "Revisión Preliminar de la Familia Procyonidae en Colombia: Preliminary Review of the Procyonidae in Colombia." Acta Biológica Colombiana 9(1):69-76. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Available at: http://scienti.colciencias.gov.co:8084/publindex/docs/articulos/0120-548X/2290574/2295170.pdf

Hamilton V. (1995). Jaguarundi. Blue Sky Press.

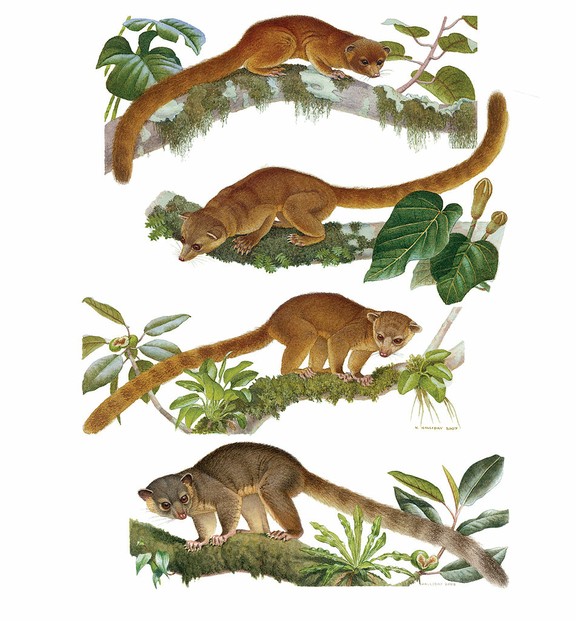

Helgen K.M., R. Kays, L.E. Helgen, M.T.N. Tsuchiya-Jerep, C.M. Pinto, K.P. Koepfli, E. Eizirik, J.E. Maldonado. (2009). "Taxonomic boundaries and geographic distributions revealed by an integrative systematic overview of the mountain coatis, Nasuella (Carnivora: Procyonidae)." Small Carnivore Conservation 41:65-74. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Available at: http://www.smallcarnivoreconservation.org/sccwiki/images/1/14/SCC41_Helgen_et_al_2009.pdf

Landau E. (1996). Tropical Forest Mammals.Children's Press.

Layne J.M. (1997). "Nonindigenous Mammals." In: Strangers in Paradise: Impact and Management of Nonindigenous Species in Florida Edited by D. Simberloff, D.C. Schmitz and T.C. Brown. Island Press, pp. 170-171.

Lydekker, Richard, ed. (1894). The Royal Natural History. Illustrated with Seventy-two Coloured Plates and Sixteen Hundred Engravings. Vol. II Section III. London and New York: Frederick Warne & Co. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: http://biodiversitylibrary.org/item/54514#page/9/mode/1up

Marceau J. (2001). Nasua narica white-nosed coati. In: Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Press. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Available at: http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Nasua_narica.html

Murie O.J. (1982). Animal Tracks. Houghton Mifflin Co: Peterson Field Guide Series.

"Nasua narica." Integrated Taxonomic Information System Collection of Life. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Available at: http://www.catalogueoflife.org/col/details/species/id/6862825

"Nasua narica." Integrated Taxonomic Information System Report. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Available at: http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=552462

"Nasua narica white-nosed coati." Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Available at: http://eol.org/pages/311953/overview

"North American Mammals: Nasua narica White-nosed coati." Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Available at: http://www.mnh.si.edu/mna/image_info.cfm?species_id=208

Perkins M. (2006). "Mammals of North America: Land of the Coati-Mundi." Mutual of Omaha's Wild Kingdom: The Definitive 50-Episode Collection. Brentwood Home Video: Disc 4 Side B.

"Procyonids: Raccoons, Ringtails & Coatis." Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Available at: http://www.desertmuseum.org/books/nhsd_procyonids.html

Quiroga, Horacio. (2003). Cuentos de la Selva. Reysa Ediciones.

Reid F.A. (2009). A Field Guide to the Mammals of Central America and Southeast Mexico. Oxford University Press.

Schindler, S.D. (2013). Spike and Ike Take a Hike. Nancy Paulsen Books.

Schmidly D.J. and W.B. Davis. (2004). The Mammals of Texas. University of Texas Press.

Sullivan, Pat Harvey. (2002). Raccoons and Their Relatives. World Book.

"Tábąąh mąʼii bíchį́į́h nineezí." nv.wikipedia.org. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Available at: http://nv.wikipedia.org/wiki/T%C3%A1b%C4%85%C4%85h_m%C4%85%CA%BCii_b%C3%ADch%C4%AF%CC%81%C4%AF%CC%81h_nineez%C3%AD

Taylor D. (2009). Predators of North America. Boston Mills Press.

"White-nosed coati." en.wikipedia.org. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White-nosed_Coati

"White-nosed coati (Nasua narica)." Comparative Mammalian Brain Collections. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Available at: http://brainmuseum.org/Specimens/carnivora/coatimundi/index.html

"White-nosed coati Nasua narica." eNature.com. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Available at: http://www.enature.com/fieldguides/detail.asp?allSpecies=y&searchText=nasua%20narica&curGroupID=5&lgfromWhere=&curPageNum=1

"White-nosed coati (Nasua narica)." Discovery Travel World, SA: Costa Rica Expeditions. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Available at: http://www.1-costaricalink.com/costa_rica_fauna/white_nosed_coati.htm

Wilson D.E. and D.M. Reeder. (2005). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. 3rd edition. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Comments

AbbyFitz, Me, too: I'd welcome a scampering coati in my yard, as well.

These are so cute. I don't think I'd mind having one of these scamper through my yard