Allen J.A. (1877). "Additional note on Bassaricyon gabbii." Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 29:267-268. Retrieved on January 13, 2014.

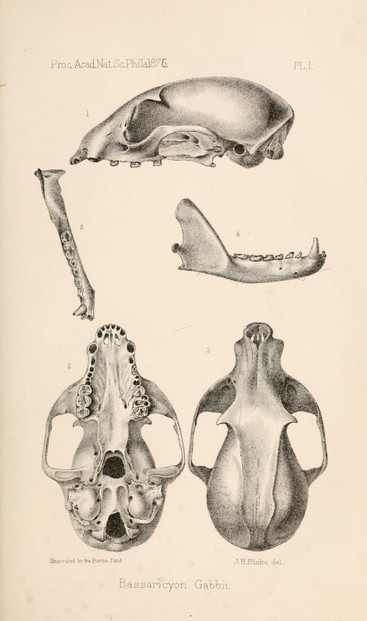

Allen J.A. (1876). "Description of a new generic type (Bassaricyon) of Procyonida, from Costa Rica." Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 28:20-23. Retrieved on January 13, 2014.

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/26298722

- Available via Internet Archive at: https://archive.org/details/proceedingsofaca28acad/page/20/mode/1up

"Bassaricyon alleni -- Allen's Olingo." InfoNatura: Animals and Ecosystems of Latin America [web application]. 2007. Version 5.0. Arlington, VA: NatureServe. Retrieved on January 13, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.natureserve.org/infonatura/servlet/InfoNatura?searchName=Bassaricyon+alleni

"Bassaricyon gabbii -- Bushy-tailed Olingo." Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved on January 13, 2014.

- Available via Encyclopedia of Life at: http://eol.org/pages/328060/details

"Bassaricyon gabbii -- Olingo." InfoNatura: Animals and Ecosystems of Latin America [web application]. 2007. Version 5.0. Arlington, VA: NatureServe. Retrieved on January 13, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.natureserve.org/infonatura/servlet/InfoNatura?searchName=Bassaricyon+gabbii

Berger L. (2004). "Bassaricyon gabbii - olingo." Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved on January 13, 2014.

- Available at: http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Bassaricyon_gabbii.html

Eisenberg J.F. (1989). Mammals of the Neotropics. Volume 1: The Northern Neotropics. University of Chicago Press.

Engstrom M.D.; Lim B.K.; Reid F.A. (1999). "Olingo." In: Guide to the Mammals of Iwokrama (Online Guide). Iwokrama International Centre for Rain Forest Conservation and Development. Retrieved on January 13, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.iwokrama.org/mammals/frame.html

González-Maya J.F. and Belant J.L. (December 2010). "Range extension and sociality of Bushy-tailed Olingo Bassaricyon gabbii in Costa Rica." Small Carnivore Conservation 43:37-39. Retrieved on January 13, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.academia.edu/388421/Range_extension_and_sociality_of_Bushy-tailed_Olingo_Bassaricyon_gabbii_in_Costa_Rica

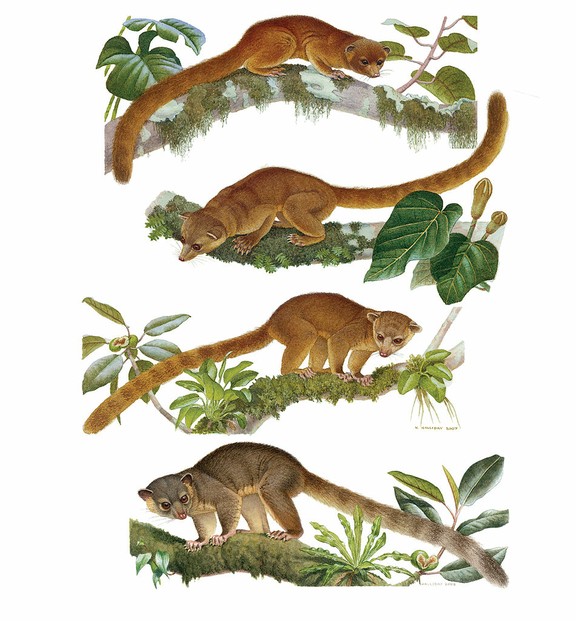

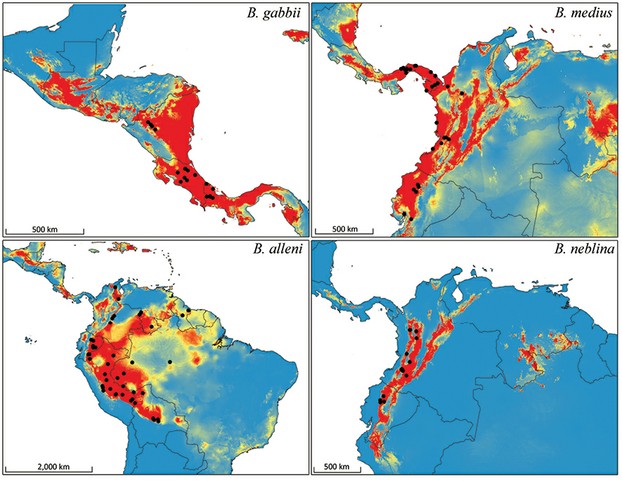

Helgen, K. M., M. Pinto, R. Kays, L. Helgen, M. Tsuchiya, A. Quinn, D. Wilson, J. Maldonado. (15 August 2013). "Taxonomic Revision of the Olingos (Bassaricyon), with Description of a New Species, the Olinguito." ZooKeys 324:1-83. Retrieved on January 4, 2014. DOI:10.3897/zookeys.324.5827

- Available via National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3760134/

- Available via Pensoft Publishers/ZooKeys @ https://zookeys.pensoft.net/articles.php?id=3550

"John F. Kennedy Speeches: Radio and Television Address to the American People on the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, July 26, 1963." John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Retrieved on January 13, 2013.

- Available at: http://www.jfklibrary.org/Research/Research-Aids/JFK-Speeches/Nuclear-Test-Ban-Treaty_19630726.aspx

Kays R.W. (2000). "The behavior and ecology of olingos (Bassaricyon gabbii) and their competition with kinkajous (Potos flavus) in central Panama." Mammalia 64:1-10.

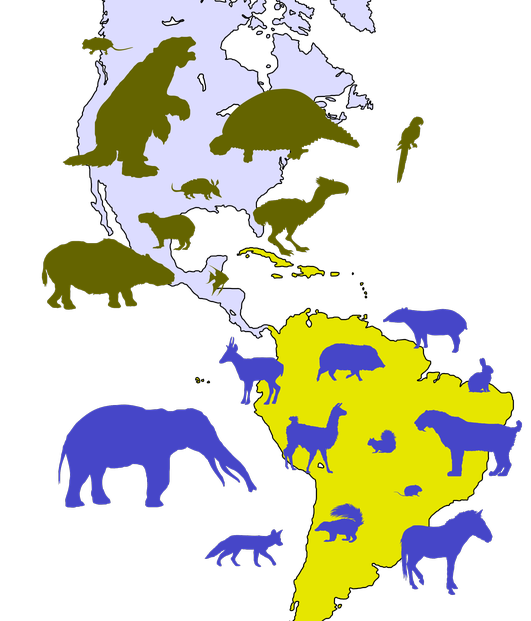

Koepfli K.-P.; Gompper M.E.; Eizirik E.; Ho C.-C.; Linden L.; Maldonado J.E.; Wayne R.K. (2007). "Phylogeny of the Procyonidae (Mammalia: Carnivora): Molecules, morphology and the Great American Interchange." Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 43(3):1076-1095. Retrieved on January 13, 2014.

- Available at: http://web.missouri.edu/~gompperm/Koepfli%20et%20al%202007%20MPE%20%28procyonid%20phylogenetics%29.pdf

"Olingo (Bassaricyon gabbii)." Pró-Carnívoros. Retrieved on January 13, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.procarnivoros.org.br/en/animais1.asp?cod=33

Pontes, A. R. M. and Chivers, D. J. (2002). "Abundance, habitat use and conservation of the olingo Bassaricyon sp in Maraca Ecological Station, Roraima, Brazilian Amazonia. Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment 37:105-109.

Prange S. and Prange T.J. (26 February 2009). "Bassaricyon gabbii (Carnivora: Procyonidae)." Mammalian Species 826:1-7. Retrieved on January 13, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.science.smith.edu/msi/pdf/i1545-1410-826-1-1.pdf

Reid F. and Helgen K. (2008). Bassaricyon alleni. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved on January 13, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/41678/0

Reid F. and Helgen K. (2008). Bassaricyon gabbii. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved on January 13, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/2609/0

Sampaio R.; Munari D.P.; Röhe F.; Ravetta A.L.; Rubim P.; Farias I.P.; da Silva M.F.F.; Cohn-Haft M. (2010). "New distribution limits of Bassaricyon alleni Thomas 1880 and insights on an overlooked species in the Western Brazilian Amazon." Mammalia 74(3):323-327.

Wozencraft W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora: Genus Bassaricyon." In: Wilson D.E. and Reeder D.M. (Eds.) Mammal Species of the World: a taxonomic and geographic reference, third edition. Johns Hopkins University Press. Retrieved on January 13, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.departments.bucknell.edu/biology/resources/msw3/browse.asp?id=14001596

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Comments

VioletteRose, Olingos definitely give the impression, when looking into their eyes, that they are looking back. They are charmers.

wow great eyes he has, interesting article!