Allen, Joel Asaph. (1916). Autobiographical Notes and A Bibliography of the Scientific Publications of Joel Aseph Allen. New York: The Museum.

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/44824456

- Available via Internet Archive at: https://archive.org/details/autobiographical00alleiala

"Bassaricyon neblina." es.wikipedia.org. Retrieved on January 4, 2014.

- Available at: http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bassaricyon_neblina

"Bassaricyon neblina." Wikispecies. Retrieved on January 4, 2014.

- Available at: http://species.wikimedia.org/wiki/Bassaricyon_neblina

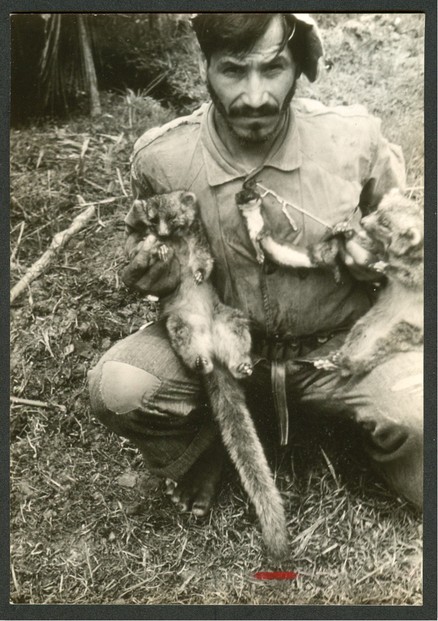

Becker, Dr. Marty. "Baby Olinguito Found in Colombia." MSN Living:

Family & Kids, Pets. Retrieved on January 4, 2014.

- Available at: http://living.msn.com/family-parenting/pets/baby-olinguito-found-in-colombia

Bittel, Jason. (22 August 2013). "Seznamte se, to je olinguito." TabletMedia. Retrieved on January 4, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.tabletmedia.cz/cz/seznamte-se-to-je-olinguito/#

Borenstein, Seth. (15 August 2013). "Adorable New Mammal Species Found in 'Plain Sight'." Internet Archive Wayback Machine: ABC News. Retrieved on January 4, 2014.

- Available at: http://web.archive.org/web/20130816013321/http://abcnews.go.com/Technology/wireStory/adorable-mammal-species-found-plain-sight-19967921

Collins, Nick. (15 August 2013). "Olinguito is First New Carnivore in 35 Years." The Daily Telegraph: Science News. Retrieved on January 4, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/science/science-news/10245618/Olinguito-is-first-new-carnivore-in-35-years.html

"Cutest Carnivora Mammal Discovered Called 'Olinguito'." W3GK: Animals, Wildlife. Retrieved on January 4, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.w3gk.com/2013/08/cutest-carnivora-mammal-olinguito.html

"Dite ciao all'olinguito." Il Post: Scienza. Retrieved on January 4, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.ilpost.it/2013/08/15/olinguito/

Griffiths, Sarah. (15 August 2013). "Meet the Olinguito, the Shy 'Bear Cat' That's the First New Carnivore to be Discovered in the West for 35 Years." The Daily Mail: Science. Retrieved on January 4, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-2394475/Meet-olinguito-shy-bear-cat-thats-new-carnivore-discovered-West-35-years.html

Hance, Jeremy. (18 August 2013). "Meet the BABY Olinguito." Mongabay Environmental News. Retrieved on January 4, 2014.

- Available at: http://news.mongabay.com/2013/0818-hance-baby-olinguito.html

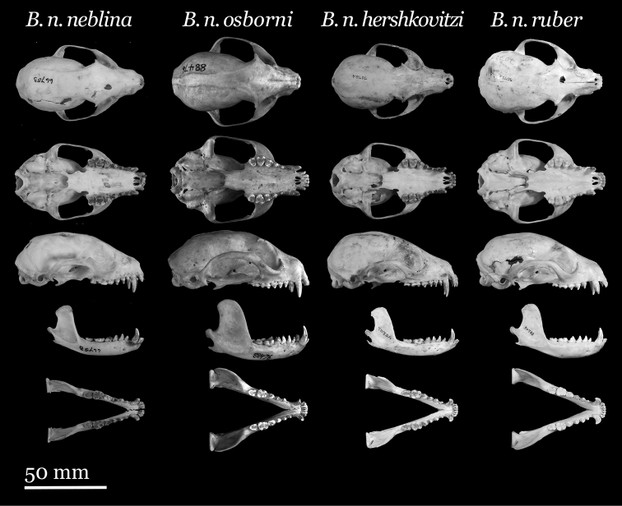

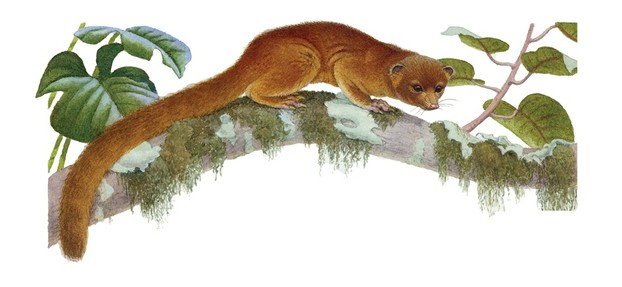

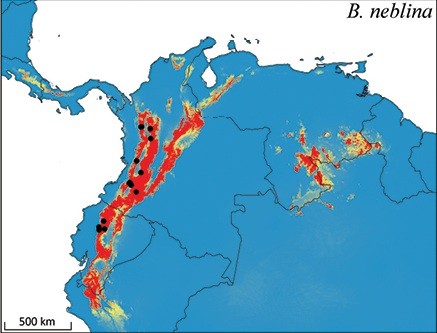

Helgen, K. M., M. Pinto, R. Kays, L. Helgen, M. Tsuchiya, A. Quinn, D. Wilson, J. Maldonado. (15 August 2013). "Taxonomic Revision of the Olingos (Bassaricyon), with Description of a New Species, the Olinguito." ZooKeys 324:1-83. Retrieved on January 4, 2014. DOI:10.3897/zookeys.324.5827

- Available via National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3760134/

- Available via Pensoft Publishers/ZooKeys @ https://zookeys.pensoft.net/articles.php?id=3550

"Kleinbär Olinguito." Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung: Gesellschaft. Retrieved on January 4, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.faz.net/aktuell/gesellschaft/kleinbaer-olinguito-forscher-entdecken-neue-raubtierart-12533435.html

Landau, Elizabeth. (15 August 2013). "New Cute Furry Mammal Species Discovered." CNN: Trends. Retrieved on January 4, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.cnn.com/2013/08/15/world/americas/new-mammal-smithsonian/

Meeri, Kim. (16 August 2013). "Smithsonian Unearths a New Species of Mammal: The Olinguito." Washington Post: Health & Science. Retrieved on January 4, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/smithsonian-unearths-a-new-species-of-carnivore---the-olinguito/2013/08/15/2fb13b6c-051a-11e3-a07f-49ddc7417125_story.html

Mole, Beth. (15 August 2013). "Cute Mammal is First Carnivore Discovered in Western Hemisphere in 35 Years." Nature News & Comment. Retrieved on January 4, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.nature.com/news/cute-mammal-is-first-carnivore-discovered-in-western-hemisphere-for-35-years-1.13565

"A New Animal: Peekaboo." The Economist: Science & Technology. Retrieved on January 4, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.economist.com/news/science-and-technology/21583594-peekaboo

"New Mammal Discovered in Andean Cloud Forest." CBC News: Technology & Science. Retrieved on January 4, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.cbc.ca/news/technology/new-mammal-discovered-in-andean-cloud-forest-1.1378835

"Nova espécie de carnívoro descoberto na América do Sul." O Globo: Ciência. Retrieved on January 4, 2014.

- Available at: http://oglobo.globo.com/ciencia/nova-especie-de-carnivoro-descoberto-na-america-do-sul-9552712

O'Brien, Jane. (15 August 2013). "Olinguito: 'Overlooked' Mammal Carnivore is Major Discovery." BBC News: Science and Environment. Retrieved on January 4, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-23701151

"Olinguito." en.wikipedia.org. Retrieved on January 4, 2014.

- Available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Olinguito

"Olinguito, primer descubrimento de especie carnívora en las Américas en 35 años." ABC: Actualidad. Retrieved on January 4, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.abc.es/ciencia/20130815/abci-nueva-especie-carnivora-olinguito-201308151703.html

Ramos, Graça Andrade. (15 August 2013). "Descoberta nova espécie de mamífero, o Olinguito." RTP Notícias: Mundo. Retrieved on January 4, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.rtp.pt/noticias/index.php?article=673910&tm=7&layout=121&visual=49

Sample, Ian. (15 August 2013). "Carnivore 'Teddy Bear' Emerges from the Mists of Ecuador." The Guardian: Taxonomy. Retrieved on January 4, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/science/2013/aug/15/teddy-bear-olinguito-ecuador-carnivore

Silva Herrera, Javier. (15 August 2013). "Nace un olinguito para nuestra biodiversidad." El Tiempo: Vida de Hoy Ciencia. Retrieved on January 4, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.eltiempo.com/vida-de-hoy/ciencia/ARTICULO-WEB-NEW_NOTA_INTERIOR-12992722.html

"Smithsonian Scientists Discover New Carnivore: The Olinguito." Smithsonian Science: Conservation Biology. Retrieved on January 4, 2014.

- Available at: http://smithsonianscience.org/2013/08/olinguito/

Stromberg, Joseph. (15 August 2013). "For the First Time in 35 Years, A New Carnivorous Mammal Species is Discovered in the American Continents." Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved on January 4, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/For-the-First-Time-in-35-Years-A-New-Carnivorous-Mammal-Species-is-Discovered-in-the-Western-Hemisphere--219762981.html#New-Mammal-Olinguito-1.png

Velástegui, Cecilia. (2013). "Olinguito Speaks Up / Olinguito Alza la Voz." Libros Publishing LLC.

Wells. Georgia. "House Cat + Teddy Bear = The Olinguito." The Wall Street Journal: Arts & Entertainment Speakeasy. Retrieved on January 4, 2014.

- Available at: http://blogs.wsj.com/speakeasy/2013/08/15/house-cat-teddy-bear-the-olinguito/

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Comments

AbbyFitz, It's fun to spotlight all these ringtails, so I'm happy that you're enjoying this series. These adorable critters have often been misidentified, so I'm enjoying clearing the confusion.

It's especially exciting to spotlight Olinguitos, which have been hiding in plain sight for so long.

I love all these animals you're introducing me too. There's so many I haven't heard of before