"American Harrier (Circus hudsonius) (Linnaeus, 1766)." Avibase the world bird database managed by D. Lepage. Retrieved on February 6, 2014.

- Available at: http://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/species.jsp?avibaseid=A091D50AA92D949C

Audubon, John James. The Birds of America, From Drawings Made in the United States and Their Territories. Volume I. New York: J.J. Audubon; Philadelphia: J.B. Chevalier, 1840. Retrieved on February 6, 2014.

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/40383032

Baicich P.; C. Harrison. (1997). A Guide to the Nests, Eggs, and Nestlings of North American Birds. New York City, NY: Academic Press.

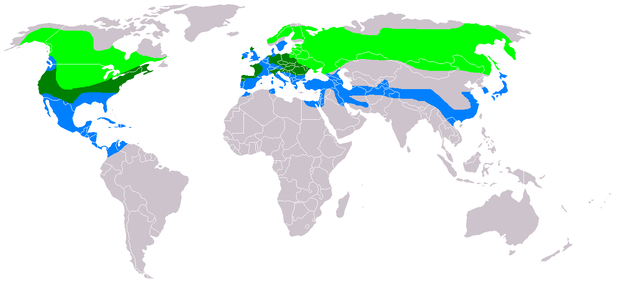

BirdLife International. (2013). "Circus cyaneus." IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved on February 6, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/22695384/0

BirdLife International. (2014). "Species factsheet: Circus cyaneus." Threatened Birds of the World. Retrieved on February 6, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/speciesfactsheet.php?id=3407

Hamerstrom, Frances. 1986. Harrier, Hawk of the Marshes: The Hawk That Is Ruled by a Mouse. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1986.

"The Harrier Hawk." The Wonder of Birds. Retrieved on February 6, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.thewonderofbirds.com/harrier-hawk/

"Hen harrier Circus cyaneus." In: Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia, 2nd edition. Volume 8, Birds I, edited by M. Hutchins, J.A. Jackson, W.J. Bock, and D. Olendorf. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group, 2002.

"Hen or American Harrier." (Circus [cyaneus or hudsonius]) (Linnaeus, 1766)." Avibase the world bird database managed by D. Lepage. Retrieved on February 6, 2014.

- Available at: http://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/species.jsp?avibaseid=82745BAA8BE0E1BE

Limas, B. 2001. "Circus cyaneus" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web

Limas B. (2001). "Circus cyaneus (On-line)." Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved on February 6, 2014.

Limas, B. 2001. "Circus cyaneus" (On-line), Animal Diversity WebRetrieved on January 29, 2014.

- Available at: http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Circus_cyaneus.html

Merrill J. (1998). "Marsh Hawk." Great Salt Lake Food Web. Retrieved on February 6, 2014.

- Available at: http://people.westminstercollege.edu/faculty/tharrison/gslfood/studentpages/hawk.htm

"Northern harrier (Circus cyaneus)." ARKive. Retrieved on February 6, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.arkive.org/northern-harrier/circus-cyaneus/#src=portletV3api

"Northern Harrier (Circus cyaneus). Wildlife Fact Sheets. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Retrieved on February 6, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/huntwild/wild/species/harrier/

"Northern Harrier Circus hudsonius." The Peregrine Fund. Global Raptor Information Network, 2014. Retrieved on February 6, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.globalraptors.org/grin/SpeciesResults.asp?specID=8366

"Northern Harrier, Life History." All About Birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved on February 6, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/northern_harrier/lifehistory

"Northern Harriers." Avian Web. Retrieved on February 6, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.avianweb.com/northernharriers.html

"Raptors Order Accipitriformes: Kites, Hawks and Eagles Family Accipitridae. In: IOC World Bird List, version 4.1, edited by F. Gill and D. Donsker. International Ornithologists' Union, 2014. Retrieved on February 6, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.worldbirdnames.org/n-raptors.html

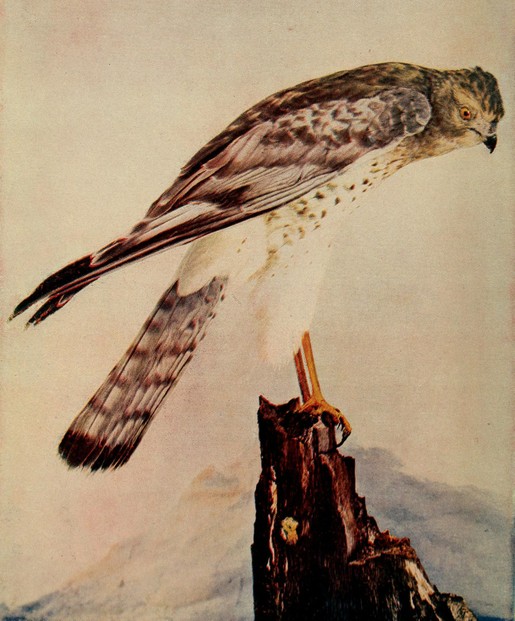

Thurber, Collins. "The Marsh Hawk (Circus hudsonius)." Pages 201-202. In: William Kerr Higley, ed., Birds and Nature in Natural Colors. Forty Illustrations by Color Photography. A Guide in the Study of Nature. Volume I. Chicago IL: A.W. Mumford, 1905. Retrieved on February 6, 2014.

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/36105841

Warren, B.H. (Benjamin Harry). Report on the Birds of Pennsylvania. With Special Reference to the Food-Habits, Based on Over Three Thousand Stomach Examinations. Harrisburg PA: Edwin K. Meyers, 1888. Retrieved on February 6, 2014.

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/14463745

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Comments

Mira, In kleptoparasitism, one predator steals the prey that has been captured by another predator. Ringtail marsh hawks and short-eared owls have a history of buzzing around one another about prey, and usually the ringtails win: they let short-eared owls do all the work of capturing prey, and then ringtails pester the owls into abandoning or dropping their prey.

It's one of those games that predators prey -- I mean: play. :-)

So why are they called kleptoparasitic again? One of them lays the pray somewhere and the other steals it?

VioletteRose, Me, too, I agree that ring-tail marsh hawks look great.

Nature is filled with beautiful, interesting creatures and plants, so I enjoy sharing my favorites. Ringtails are special favorites for me.

They look great! I really enjoy reading your articles on many different animals and birds, they are very informative. Thank you.