Arizona Capitol Museum. "Arizona State Mammal: Ringtail (Bassariscus astutus)." Arizona State Library. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- Available at: http://www.azlibrary.gov/museum/symb-mamm.aspx

"Arizona State Mammal." Arizona State Symbols. statesymbolsusa.org. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- Available at: http://www.statesymbolsusa.org/Arizona/mammal_ringtail.html

Audubon J.J. and J. Bachman. (1849-1854). The Quadrupeds of North America. Edited and with new text by Victor H. Cahalane in 1967. Hammond Incorporated: The Imperial Collection of Audubon Animals.

"Bassariscus astutus." es.wikipedia.org. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- Available at: http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bassariscus_astutus

Bassariscus astutus. Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- Available at: http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=180577

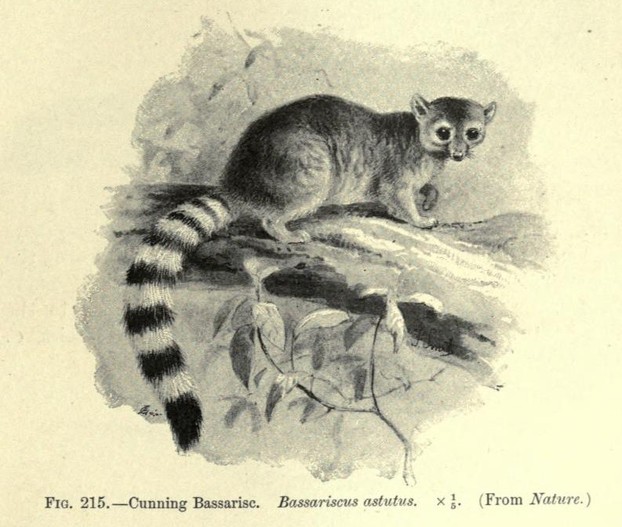

Beddard, F. (Frank Evers). "Fam. 6 Procyonidae." Pages 426-431. Mammalia. Illustrations by Mr. Dixon and to Mr. M. P. Parker. In: S. F. Harmer and A. E. Shipley, eds., The Cambridge Natural History, Vol. X. New York City: Macmillan Company, 1902.

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/1005810

- Available via Project Gutenberg at: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/39887/39887-h/39887-h.htm

Childers M.K. "Ringtail." whozoo.org. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- Available at: http://www.whozoo.org/Intro2002/MeliChild/MKC_Ringtail.htm

de Magalhaes J.P., Budovsky A., Lehmann G., Costa J., Li Y., Fraifeld V., Church G.M. (2009). "AnAge Entry for Bassariscus astutus." The Human Aging Genomic Resources: online databases and tools for biogerontologists. genomics.senescence.info. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- Available at: http://genomics.senescence.info/species/entry.php?species=Bassariscus_astutus

Goldberg, Jeffrey. (2003). Bassariscus astutus. In: Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Press. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- Available at: http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Bassariscus_astutus.html

Hunter, Luke. (2011). Carnivores of the World. Princeton University Press.

"Mąʼii dootłʼizhí." nv.wikipedia.org. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- Available at: http://nv.wikipedia.org/wiki/M%C4%85%CA%BCii_doot%C5%82%CA%BCizh%C3%AD

Nowak, Ronald M. (2005). Walker's Carnivores of the World. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Rhoads, Samuel N. (1893). "Geographic Variation in Bassariscus astutus, with Description of a New Subspecies." Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences at Philadelphia, Vol. 45: 413-418.

- Available via Internet Archive at: https://archive.org/details/jstor-4062043

"Ring-tailed Cat." en.wikipedia.org. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- Available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ring-tailed_cat

Ringtail Bassariscus astutus. enature.com. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- Available at: http://www.enature.com/fieldguides/detail.asp?allSpecies=y&searchText=bassariscus&curGroupID=5&lgfromWhere=&curPageNum=1

"Ringtail (Bassariscus astutus)." The Mammals of Texas -- Online Edition. nsrl.ttu.edu. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- Available at: http://www.nsrl.ttu.edu/tmot1/bassastu.htm

"Ringtail (Bassariscus astutus)." Pima Community College: Desert Ecology of Tucson A2. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- Available at: http://wc.pima.edu/Bfiero/tucsonecology/animals/mamm_ring.htm

Ringtail (Bassariscus astutus). vivanatura.org. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- Available at: http://www.vivanatura.org/Bassariscus_astutus.html

- Available at: http://www.vivanatura.org/Bassariscus_astutusPhotos.html

Timm R., Reid F., and Helgen K. (2008). Bassariscus astutus. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- Available at: http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/41680/0

Williams, David B. "Ringtails Cat (Bassariscus astutus)." DesertUSA.com. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- Available at: http://www.desertusa.com/mag01/mar/papr/ringt.html

Wilson D.E. and Reeder D.M. (2005). Bassariscus astutus. In: Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. 3rd edition. Johns Hopkins University Press. bucknell.edu. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- http://www.departments.bucknell.edu/biology/resources/msw3/browse.asp?id=14001603

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Comments

Elsewhere, I consider museum, school, world gardens of wild animal and plant sentients.

A designated ringtail garden of such a type delights me in the ringtail-host plants and in the ringtail-predator and prey animals.

For example, a ringtail garden includes such woody-plant iterations as chaparral shrublands; juniper, oak, pinyon-pine woodlands; and mountain-conifer forests.

Wouldn't such a model garden, perhaps as bonsai, be wonderfully wondrous with lego or plush-toy ringtails?

Hackberries and persimmons appeal to ringtails and ... -- ;-D -- to me!

The ringtail diet of moistly edible berries and fruits and of clean, clear water can be so easily configured into our diets, can't they?

Hackberry and persimmon fruits ensure us of delicious, healthy jams, jellies, juices and salads fresh and of delicious, healthy trail mixes dried.

A ringtail sentient as family member appeals to me.

Feline sentients in the wild are team members. My Gusty Gus sometimes came for food and water at unexpected times. She always "fronted" at those times for someone else, such as a hungry, orphaned opossum and -- ! -- a hungry, orphaned rooster!

So feline and ringtail sentients together probably get along. Has anyone had any experience with feline and ringtail sentients "hobnobbing" in the wild or under one roof?

Ringtails consuming painted buntings intrigues me.

Is it not said that red implies inedible scents, tastes and textures for would-be predators?

cmoneyspinner, Me, too: "I really wish they would leave the painted buntings alone." :-)

Bible fauna and flora is an area which I have researched. It's especially fascinating, with many creatures and trees, etc., mentioned. Go for it!

uptanabe, You never know! You might one day have the pleasure of meeting a ringtail. They are happy as pets.

AbbyFitz, Me, too: ring-tailed cats do have an exotic aura!

I'm OK with all the other stuff the ring tails eat. But I really wish they would leave the painted buntings alone. This article caused me to look up the state mammal for Texas. I thought it was the armadillo. Turns out we have several official mammals - armadillo, long horns, bats, etc. UM ... not enough for me to write about though. :) (Just kidding.)

( http://www.netstate.com/states/tables... )

I'm not really into animals. It would take a lot of research to write about some. Although I toyed with the idea of Bible creatures - leviathan, behemoth, stuff like that. I'll think on it some more. Good article!!

Oh cute indeed! I didn't know much about these little "cats" - of course they don't live in the Northeast like me so I doubt I'll meet one.

They are so cute! But they look like they would not be native to the US, they look exotic to me.