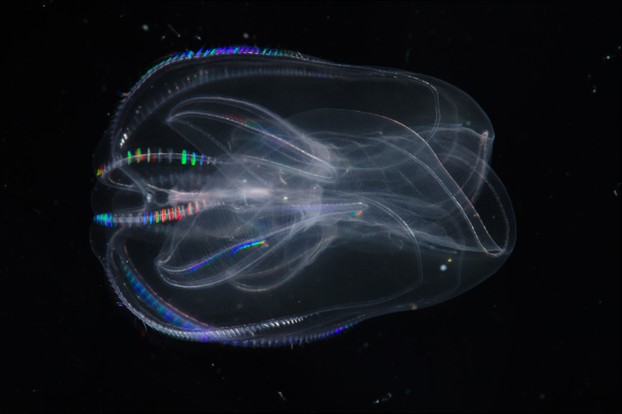

Mnemiopsis leidyi; Bergen, southwestern coastal Norway: CC BY SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sea_Walnut.tif

ca. 1870 portrait by Gilbert Studios, Philadelphia: Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Joseph_Leidy_by_Gilbert_Studios_c1870.jpg

tail of a whale: Edith Schreurs, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tail_of_a_whale_near_Valdes_Peninsula.jpg?uselang=fr

Cape Cod Railroad Bridge: Pete (Peter Gene), CC BY-SA 2.0, via Flickr @ https://www.flickr.com/photos/petebackwards/328208684/

"Hypoxic event in Greenwich Cove"; photo by Chris Deacutis, IAN (Integration and Application Network, Univ. Maryland Center for Environmental Science): eutrophication&hypoxia, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr @ https://www.flickr.com/photos/48722974@N07/4523955262/

"The Thomas Point Shoal Lighthouse in Chesapeake Bay, Maryland": PA1 Pete Milnes/US Coast Guard, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons @ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Thomas_Point_Lighthouse_Chesapeake_Bay.jpg

"Sea walnut, Boston Aquarium": Steven G. Johnson/Flickr, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fichier:Sea_walnut,_Boston_Aquarium.jpg

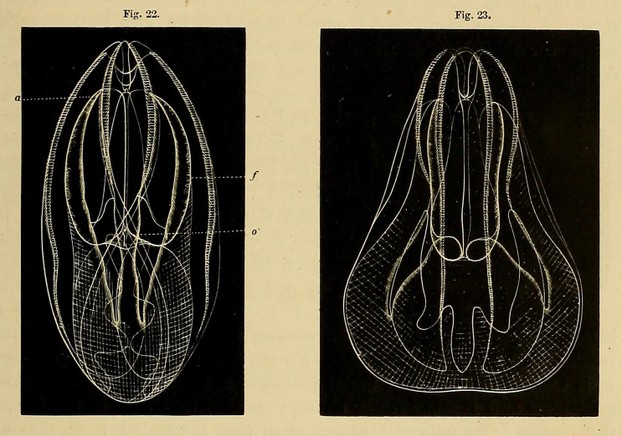

Figure 22 broad side; a=auricles; f=furrow; o=actinostome (oral opening); Figure 23 narrow side: Public Domain, via Biodiversity Heritage Library @ https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/28070415

Northern quahogs thrive in estuarial muddy sands, Winyah Bay Estuarine Research Reserve, South Carolina: NOAA Photo Library, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr @ http://www.flickr.com/photos/noaaphotolib/5114728190/

brine shrimp (Artemia salina): Hans Hallewaert, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Artemia_salina_1.jpg

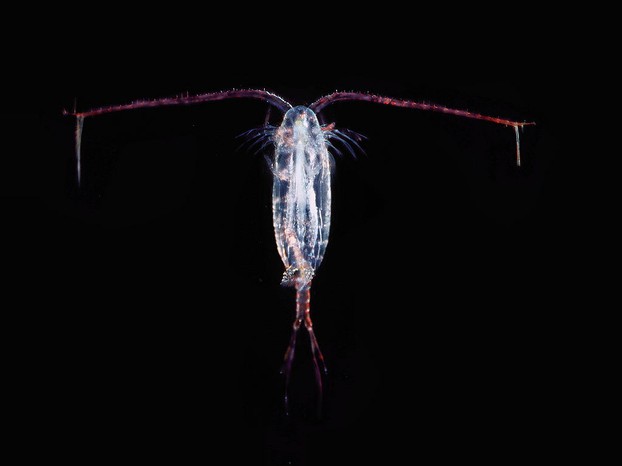

copepod: Uwe Kils, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Copepodkils.jpg

Dermochelys coriacea: Hannes Grobe/AWI, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lederschildkr_dermochelys-coriacea-senkenberg_hg.jpg

Atlantic sea nettle (Chrysaora quinquecirrha); Grey's Reef National Marine Sanctuary, Georgia; photo by Greg McFall, Gray's Reef NMS, NOS, NOAA: NOAA Photo Library, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr @ https://www.flickr.com/photos/noaaphotolib/5029593133/

lion's mane jellyfish: Erik Solheim (erikso), CC BY-SA 2.0, via Flickr @ https://www.flickr.com/photos/eirikso/4848845443/

view of Atlantic Ocean from Beavertail State Park, southern Conanicut Island, Rhode Island: Roger LeJeune (dadofliz), CC BY-ND 2.0, via Flickr @ https://www.flickr.com/photos/dadofliz/5487032207/

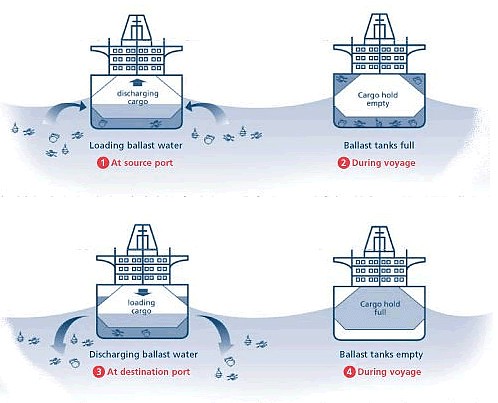

concept, content and design: Steve Raaymakers and Daniel West and Associates, London: International Maritime Organization, CC BY 2.0, via NOAA @ http://stateofthecoast.noaa.gov/invasives/ballast_water.html

How the comb-jelly (Mnemiopsis leidyi) is spreading through European seas (invasive species): Philippe Rekacewicz, CC BY NC SA 2.0, via UNEP/GRID-Arendal @ http://www.grida.no/graphicslib/detail/how-the-comb-jelly-mnemiopsis-leidyi-is-spreading-through-european-seas-invasive-species_727d

European anchovies (Engraulis encrasicolus), Ligurian Sea, Italy: Etrusko25, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Acciughe_2.jpg

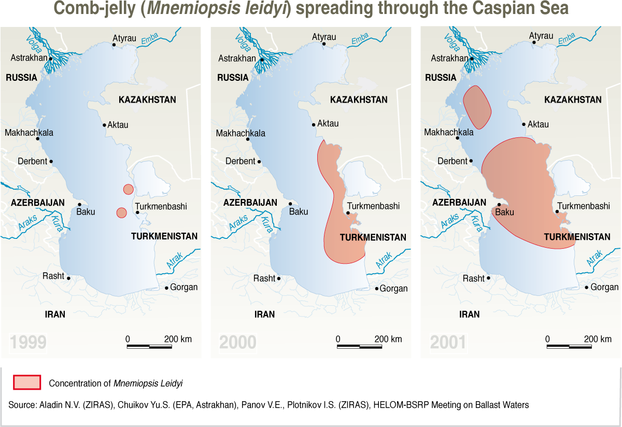

Comb-jelly (Mnemiopsis leidyi) spreading through the Caspian Sea (invasive species): Hugh Ahlenius, CC BY NC SA 2.0, via UNEP/GRID-Arendal @ http://www.grida.no/graphicslib/detail/comb-jelly-mnemiopsis-leidyi-spreading-through-the-caspian-sea-invasive-species_11bd

Beroe ovata on the Black sea offshore: CristianChirita, GNU 1.2, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Medusa010.jpg

western Caspian Sea along Baku Boulevard (Azerbaijani: Dənizkənarı Milli Park): Samir Rəsulov, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Baku_Bulvar.jpg

view of Atlantic Ocean from Caleta Valdés, inlet on Valdes Peninsula's east coast, near Punta Norte (northernmost point): Zuarin, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Caleta_Valdés_2.JPG

aboral (away from or opposite mouth) view of adult Mnemiopsis leidyi, caught off southern New Jersey coast: The jt, CC BY SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MLeidyi_headon_10082015.png

Baltic Sea's southern waters off Royal City of Darłowo, northwestern Poland: Argonowski, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Baltic_Sea_(Darlowo).JPG

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Comments