Socotra's frankincense branches: Gerry and Bonni, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr @ https://www.flickr.com/photos/gerr-bon/6408183409/

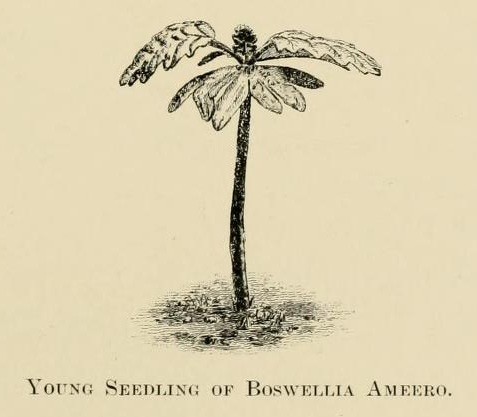

Boswellia ameero, another of Socotra's endemic frankincense trees: H.O. Forbes-Natural History (1903), page 461, Public Domain, via Biodiversity Heritage Library @ https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/24884726

Socotran Archipelago in Arabian Sea sector of Indian Ocean: Central Intelligence Agency, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons @ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Somali_map.jpg

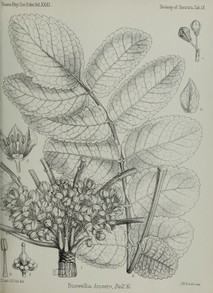

Boswellia ameero: Isaac Bayley Balfour-"Botany" (1888), Tab. IX, Public Domain, via Biodiversity Heritage Library @ http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/41401512

Socotra's camels are fond of frankincense tree's branches, leaves, and twigs: Gerry and Bonni, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr @ https://www.flickr.com/photos/gerr-bon/6408239431/

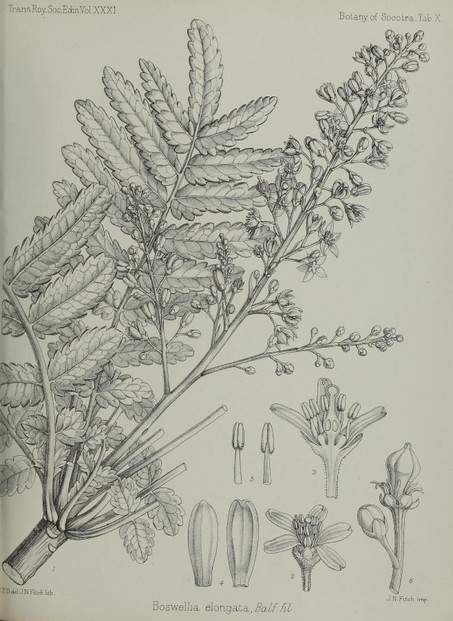

Boswellia elongata: Isaac Bayley Balfour-"Botany" (1888), Tab. X, Public Domain, via Internet Archive @ https://archive.org/details/transactionsofro311888roy/page/n570/mode/1up?view=theater

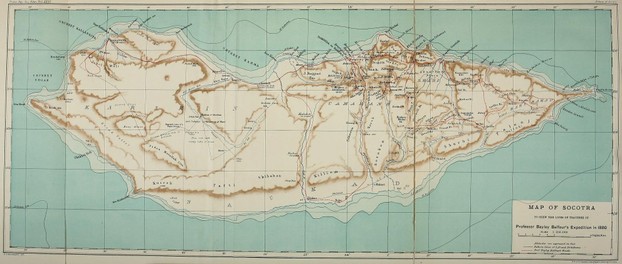

Socotra: Isaac Bayley Balfour-"Botany" (1888), frontispiece, Public Domain, via Biodiversity Heritage Library@ https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/41400959

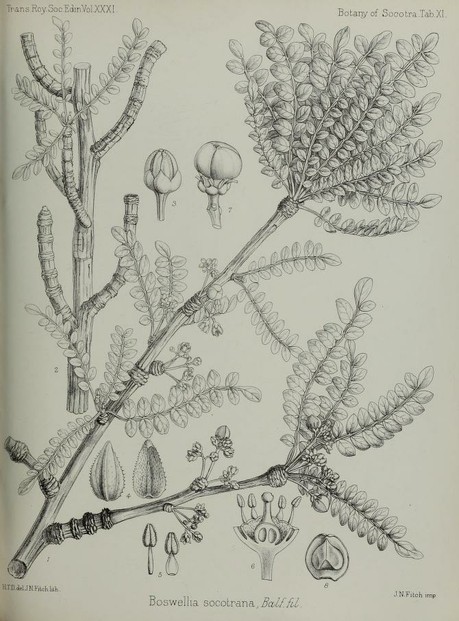

Socotra frankincense flowers and fruit: Isaac Bayley Balfour-"Botany" (1888), Tab. XI, Public Domain, via Biodiversity Heritage Library @ https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/41401520

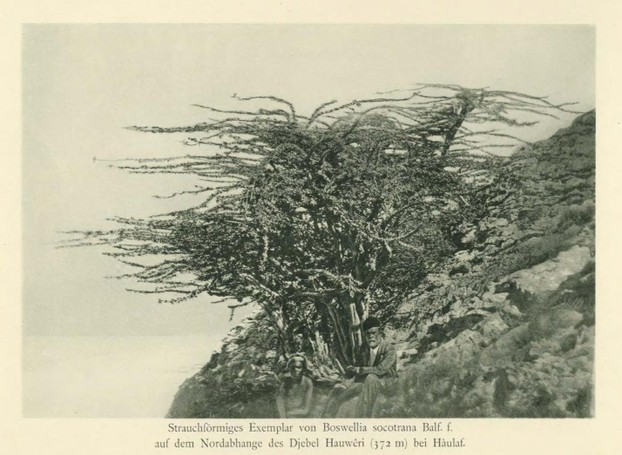

1899 photo by Captain H.E. Rosengreen: Richard von Wettstein-Sokótra 1905, page 30, Public Domain, via Internet Archive @ https://archive.org/details/Soktra1905/page/n21/mode/2up?view=theater

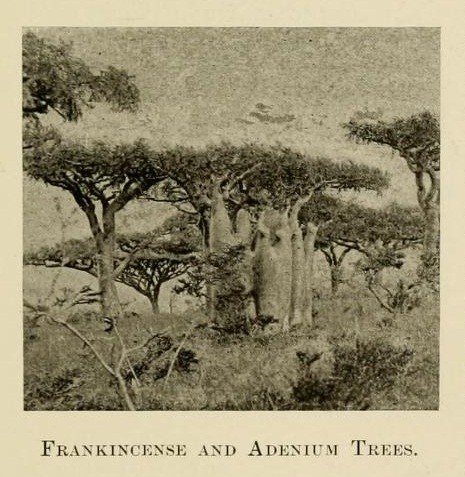

Socotra frankincense tree (left, foreground) with Adenium (center): HO Forbes-Natural History (1903), page xli, Public Domain, via Biodiversity Heritage Library @ https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/24884197

Scops socotranus: engraving by Bale & Danielsson, Ltd. after an original by Henrik Grönvold (1858–1940): HO Forbes-Natural History (1903), Plate V, page 69, Public Domain, via Biodiversity Heritage Library @ https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/24884298

Phoenix rising from its fiery ashes: Aberdeen Bestiary illuminated manuscript, ca. 12th century, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Phoenix_detail_from_Aberdeen_Bestiary.jpg

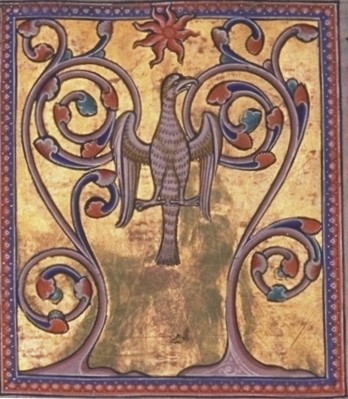

Phoenix, risen from its ashes, between two trees, frankincense and myrrh: Aberdeen Bestiary, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Phoenix_rising_from_its_ashes.jpg

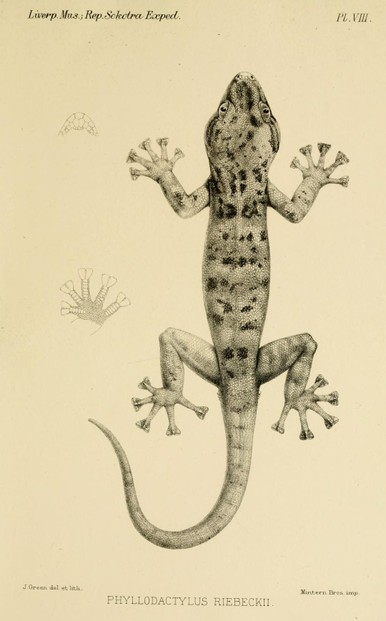

illustration/lithograph by John Green: HO Forbes-Natural History (1903), Plate VIII, page 99, Public Domain, via Internet Archive @ https://archive.org/details/naturalhistoryof00forb/page/99/mode/1up?view=theater

Socotra's aloe: Gerry and Bonni, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr @ https://www.flickr.com/photos/gerr-bon/6407177435/

Yemeni riches: frankincense, gold, oil: snotch, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Frankincense_2005-12-31.jpg

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Comments

The last subheading, Armageddon or the rise of the incense phoenix on Socotra?, alerts us that "Mythically, a saving grace inheres in the Socotran Frankincense Tree's legendary linkage to the fabled Incense Route. The early marine routes, which preceded the overland route and by which incense was traded to the ancient Egyptians over 3,500 years ago, were organized and navigated by the mysterious Phoenicians, who were unequalled anciently in their enthusiastic, skillful, and undaunted seafaring. In their careful mythology, Phoenicians believed that the nest of the phoenix, the colorfully plumed mythical bird that rises from its own ashes, was made from frankincense and myrrh (Commiphora spp) trees and was located on the highest peak of Socotra's Haggeher Mountains."

Isn't it interesting, isn't it intriguing to imagine other information that inspired ancient inhabitants to instill such invocations as the Phoenician phoenix on Socotran soil?

What else is there for us to identify?

Not only the Three Magi but also the Queen of Sheba brought frankincense, gold, myrrh gifts, respectively to the Jesus Christ child and to King Solomon.

Might it not be possible to mull the Sheba gold and spices as fine insular manifestations of metal, mineral, natural resource-rich Socotra?

The island Socotra amazes me and appeals to me so much that I appreciate it as a biogeography-, mineral and natural resource-rich area whose woody plants particularly attract me.

The tree attraction directs me to Christmas and Epiphany, to the Holy Family of Jesus, Joseph and Mary and to the Magi and their frankincense, gold and myrrh.

The comment immediately below features whether or not fabulous Socotra furnished the frankincense and myrrh of the Three Magi.

But how about going a step further with Magi gold?

The island Socotra has Medden-area gold reserves and Seiga and Shashoba gold-mining areas!

The computer crashed before I communicated another component of my observation and question in the box immediately below.

Socotran island vegetation encompasses the myrrh-enabling spiny shrubs and small trees scientifically expressed as Commiphora socotrana and Commiphora kua.

Mightn't the below-mentioned tea time manifest more magnificently, marvelously, miraculously with both frankincense and myrrh scents?

Wouldn't that work wonderfully -- as I wonder whether or not Magi frankincense and myrrh were Socotran ;-D -- during the Christmas season?

Socotra wildlife amazes me with its drinkable, edible products.

For example, isn't it interesting and intriguing to imagine a tea time with all things drinkable and edible from Socotra cucumber, dragon's blood, fig and pomegranate trees?

It would be wonderful to work Socotra-frankincense products in too, wouldn't it?

What wondrous scents, tastes and textures!

Socotran trees are so amazing that they called for ancient comments even as they command current commentaries.

Isn't it interesting to investigate such ancient languages as hieroglyphics, Hittite and Sanskrit for such information about the impressive Socotra cucumber, dragon's blood, fig, frankincense, pomegranate trees?

Online sources consider the frankincense, the gold and the myrrh of the Three Wise Men as gifts that respectively count among the considerable characteristics of Jesus Christ kingship, priesthood and death.

Isn't it intriguing to imagine anciently invoked Socotran frankincense as the source of the afore-indicated frankincense?

As with all the other Socotra woody plants that are among my wizzlies, Socotra frankincense trees cooperate with garden-museum, province- or state-, national-, international-modeled gardens.

As with all other Socotra woody plants that are among my wizzlies, Socotra frankincense cooperates with assembling all like tree-product sources to avow their similar attributes from somewhat to most awesome.

Isn't it interesting to imagine how each frankincense species iterates appearance- and efficacy- and scent- and texture-wise?