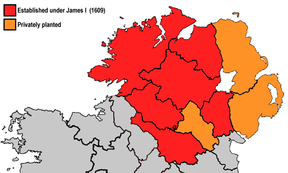

In 1609, an army belonging to King James escorted land surveyors through the counties of Donegal, Coleraine, Tyrone, Fermanagh, Cavan and Armagh. Their job was to map out the land, in order that it might be carved up for English settlers.

In 1609, an army belonging to King James escorted land surveyors through the counties of Donegal, Coleraine, Tyrone, Fermanagh, Cavan and Armagh. Their job was to map out the land, in order that it might be carved up for English settlers.

While the City of London companies set about recruiting farmers and traders willing to withstand the risks, in order to gain land of their own; King James was finalizing the way it should all proceed.

The six counties were each split into equal sections. Some portions were given to the Anglican Church in Ireland, in order to create ministries for the conversion of the native Irish from Catholicism. Some were given to veteran soldiers from the Nine Years' War, who could be expected to help protect their country-folk now too.

County Coleraine was handed over to the City of London companies. They promptly renamed the city of Derry as Londonderry, which became the name of the whole county. This would be the fortified center of British plantation.

As for the Loyalist Settlers, they were categorized in one of three ways:

Undertakers: Primarily rich London traders, these people were required to pay for the passage and settlement of ten English families on their land. There were no restrictions placed on the amount of Irish people allowed to stay as tenants to these landlords, but the native people were only to be given the least fertile land to encourage them to move on.

Servitors: These veteran soldiers were not asked to pay for those settlers on their land. But they were also permitted only five Irish tenants once there.

Both undertakers and servitors were required to build and maintain fortifications, in order to repel the Gaels and protect the settlers.

The Deserving Irish: (Yes, this category really was called that.) These people had to prove that they had taken no part in the recent rebellions against the English. They were to act as their overlords in language, culture and Protestant religion. They were allowed to retain Irish farmers on their land, who would be subservient to them. Again the native farmers could only have the least fertile ground to farm.

Many in this last category were actually ethnically British. They'd emigrated in earlier, failed plantations and had 'turned native' instead.

It's quite telling to read the terms of the Treaty of Mellifont in 1603. Agreed between Charles Blount, 8th Baron Mountjoy - the English Lord Deputy in Ireland - and Hugh Uí Néill (pictured), Ulster clan chief and nominally High King of Ireland, it is a study in dismantling a people.

It's quite telling to read the terms of the Treaty of Mellifont in 1603. Agreed between Charles Blount, 8th Baron Mountjoy - the English Lord Deputy in Ireland - and Hugh Uí Néill (pictured), Ulster clan chief and nominally High King of Ireland, it is a study in dismantling a people.

When Hugh Uí Néill was summoned to see King James in 1607, the Gaelic High King could see a future stretching out before him in the Tower of London. Or worse.

When Hugh Uí Néill was summoned to see King James in 1607, the Gaelic High King could see a future stretching out before him in the Tower of London. Or worse.

In 1609, an army belonging to King James escorted land surveyors through the counties of Donegal, Coleraine, Tyrone, Fermanagh, Cavan and Armagh. Their job was to map out the land, in order that it might be carved up for English settlers.

In 1609, an army belonging to King James escorted land surveyors through the counties of Donegal, Coleraine, Tyrone, Fermanagh, Cavan and Armagh. Their job was to map out the land, in order that it might be carved up for English settlers.

In the neighboring County Antrim and County Down, two Scottish private landlords had been doing the same since 1606. Those lands were already filling up with Lowland Scots. But the much bigger enterprise initiated from London was sluggish at best.

In the neighboring County Antrim and County Down, two Scottish private landlords had been doing the same since 1606. Those lands were already filling up with Lowland Scots. But the much bigger enterprise initiated from London was sluggish at best.

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Comments

It's not really something which could be forgotten, because it's all still right there. I was reading a couple of days ago that Belfast City Council have voted to stop flying the Union Flag.

As they did so, Loyalists (descendents of the English and Scottish settlers) began to riot outside. Cars and property were damaged, but fortunately there weren't too many injuries. Riot police were called and they were attacked too.

This was two days ago (December 2012), but it's a direct consequence of what was started in 1610.

Interesting wizzle, Jo. It's amazing how generations hold memories of injustice. Let's hope the peace lasts.

Ulster was extremely Gaelic speaking before 1610, but afterwards it went into some decline. Not immediately though. Obviously all those coming in spoke English; while all of the natives spoke Gaelic. As native people were pushed out, English came to the fore.

But in some ways, the Plantations failed as cultural genocide. There was supposed to be limits on the number of Irish people allowed on each plot, but that didn't happen in reality. The Irish could be charged huge rents, so they were favored by landlords out for cash. Also there weren't the numbers emigrating that James would have liked, so more Irish were needed to work the farmland.

Those Irish people all retained their Gaelic.

Really the death knoll for the Gaelic language as a whole came much, much later. The Irish genocide of 1845-1851 was the biggie, though only within the context of other things happening before and after. Too many Gaelic speakers died or emigrated; and the schools would only teach in English.

However, Gaelic never completely went away. There are still Gaelic speaking areas in Ireland now, though granted not in Ulster. But there are still individuals there who are fluent.

What happened to Gaelic after the Ulster plantations?

I've never even heard of that play. I'll have to look it out. But I'm sure that I've been Brian Friel's name on something today. I'm currently writing about the Nine Years' War, which happened in the decade before the Ulster Plantations. I wonder if he wrote about that too?

in A level English we studied 'translations' a play by Brian Friel. It explored these issues and I really enjoyed it. You never seen to see it performed anywhere these days though.