March 24th 1847: British people, led by Queen Victoria, held a National Day of Atonement, fasting and doing penance, for the Irish famine.[16]

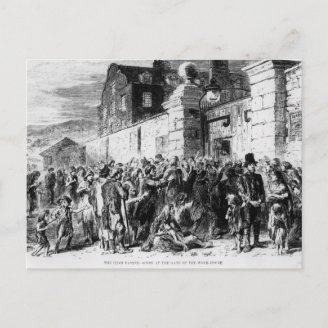

April 1847: A report, to the Central Board of Health from Killarney, showed that people were literally dropping dead in the street. 130 people were crammed into the local hospital, which had been designed to accommodate 54 patients, and the workhouse was full.[17]

April 3rd 1847: The London Times complained that ‘Pauperism in Ireland is now draining ten million (pounds) a year from the English exchequer, to that the Irish legislators make no objection; it is quite according to ‘sound principles’. Englishmen think the drain can be stopped, and (want to) fix Irish property with a rate, as they themselves were saddled with one between two and three centuries ago.'[18]

1847: William Gregory, Galway landowner and MP for Dublin, argued in Parliament against proposed legislation which would place the emphasis for relief from the British government onto the Irish landlords. He said that ‘the whole rental of Ireland would not suffice for the relief which must be required under this bill’. He claimed that it would demoralize the rural population, whilst absorbing the capital of the country, diminishing wages and reducing the laborers to paupers. In short, it would be ‘more prejudicial to the poor than the rich’.[19]

May 15th 1847: Daniel O’Connell, the famous Irish Republican politician, died.[20] He had fought long and hard for Irish freedom from Britain. But he had failed in both that and in persuading the British Parliament to take early action to stave off Irish starvation in 1845. With his health failing, he'd undertaken a pilgrimage to Rome, but only got as far as Genoa before dying.

May 1847: Public works stopped.[21] Food prices started falling just when public relief works are being stopped.[22]

June 1847: The Poor Law Amendment Act, including the Gregory Clause, was passed. This shifted the responsibility for the relief of the Irish onto the Irish landowners (usually absentee owners living in Britain) from the British Treasury. It authorized relief outside workhouses in a broad spectrum of areas. However the Gregory Clause stated that those who owned a quarter of an acre of land need not be helped. The landowners reacted by mass clearances of tenants on their lands, so the acres could be used for the more profitable cattle grazing. Those with an acre of land quickly lost it. They couldn’t use it to stop their families starving, thus it helped to consolidate land for the larger land-owners. Public opinion in Britain saw this act as benevolent.[23]

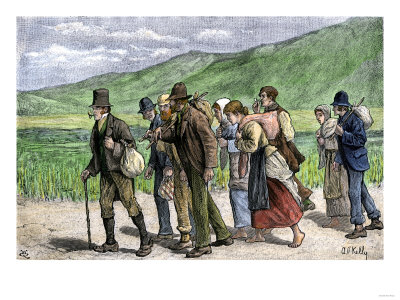

1847: There were 17,465 documented deaths in this year on the emigration ‘coffin ships’.[24] Of these, 4,572 occurred within a two-month period.[25]

June 1847: The MP for Rochdale, William Sharman Crawford, proposed a bill based on the Devon Commission, which recommended that landlords compensate outgoing tenants for any improvements done to their property. It failed by 112 votes to 25.[26]

1847: 40 Protestant clergymen died of typhus or relapsing fever, while the number of dead Catholic clergymen was double that of the year before.[27] (NB Source doesn’t give figure for the previous year.)

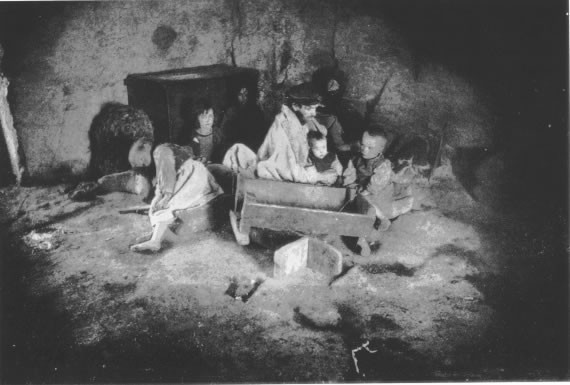

June 1847: William Kingsley, physician to the Roscrea fever hospital, in County Tipperary, wrote to the Board of Health complaining that the cabins of the poor were ‘a constant, fertile and permanent source of typhus fever, in consequence of the putrid effluvia exhaled from (the cess-pools) and blown by the wind into the interior of those filthy habitations’.[28]

July 1847: Lord Clarendon became Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.[29]

1847: The Quakers set up the British Relief Association appealing to the populations of America, England and Australia to help save the Irish. The charity benefited from two letters penned by Queen Victoria, at the beginning and later on in the year, supporting aid. The Quakers raised £470,000. Donors included £16,500 from Calcutta, £3,000 from Bombay, other amounts from Florence, Italy, Antigua, France, Jamaica and Barbados. A Native American tribe, the Choctaw, sent $710; while Jewish synagogues in Britain and America contributed generously. The British Secretary for the Treasury reacted with horror. He warned against ‘lavish charity’.[30]

1847: The Tenants’ Organization was set up in Holycross, Tipperary, by Fintan Lalor, but it remained a local affair.[31]

Aug 4th 1847: The Toronto Globe reported that, on the latest emigration ship to arrive, 158 passengers were already dead and 180 were sick. The newspaper predicted that half of the original passengers would never ‘see their home in the New World.’[32]

August 1847: Three million Irish people were being fed daily in government run soup kitchens.[33] However, the British government lost several seats in Parliament to a ‘small majority of Whig-Liberals’ opposing these soup kitchens.[34]

Aug 30th 1847: The London Times wrote: "In no other country have men talked treason until they are hoarse, and then gone about begging for sympathy from their oppressors. In no other country have the people been so liberally and unthriftily helped by the nation they denounced and defied."[35]

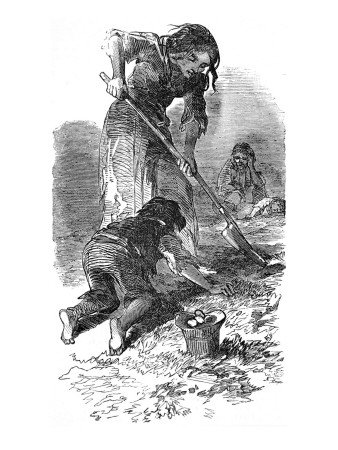

Autumn 1847: The crop blight was less severe, but little had been planted the previous year, as the seed potatoes had been eaten as food.[36] Lord Trevelyan declared that famine was over and ‘no further extraordinary measures could be justified’. [37] Government run soup kitchens, seen only as a short-term measure, closed and mortality rates rose.[38] Lord Russell commented ‘we have in the opinion of Great Britain done too much for Ireland and have lost elections for doing so.’[39]

Oct 1847: There was a British banking crisis and financial crash. Popular opinion in Britain targeted Irish relief as the cause.[40]

Late 1847: There was an upsurge in agrarian violence in Ireland.[41]

Nov 2nd 1847: John Ross Mahon, an Irish landowner, was fatally shot by the lover of a young woman whom he had forcefully evicted. The woman was now suspected drowned after leaving on one of the coffin ships, which Mahon had commissioned for his ex-tenants.[42]

Nov 1847: A Coercion Act was passed to protect landlords against the ‘murderous revenge’ of their tenants.[43]

Nov 1847: Seán Ó Dálaigh, a schoolteacher, warned in a lecture to the Dublin Confederate Club, that the Famine could see the survival of the Gaelic language brought into doubt.[44] Too many Gaelic speakers were either dying or emigrating to countries where Gaelic was not the first language.

End of 1847: Republican John Mitchel urged the Irish to arm themselves, for which he was expelled from the Young Ireland group. Mitchel then established his own republican newspaper, the ‘United Irishman’. His slogan was for ‘Ireland her own, and all therein, from the sod to the sky. The soil of Ireland for the people of Ireland, to have and to hold from God alone.’[45]

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Comments

The truth is that we'll never know precisely how many people were lost during that time. Though they can certainly be numbered in their millions.

Babies were born and died without ever being registered. Hungry people fell down in the lanes and were buried in the banks. There was a large amount of displacement going on, as people headed from the country to the larger towns and cities.

The usual figures given are over 1.5m dead and 2m emigrated, though that should be considered a minimum.

When I get chance, I'll see what I can uncover about your Mary Harrington. I'm currently writing another Wizzle about the Irish genocide, which should be published later today.

And yes, the story about what happened to the Irish, when they arrived in the new world, is a whole new testimony of horrors.

I was wrong about the 4 million said to survive. It was said to be 6 million. That doesn't account for any births during that time. I was checking out my tree and I realize a lot of my ancestors were born during those horrific 5 years and managed to live through it.

My Harrington was Mary Harrington born in or near West Meath in 1825 ish. I cannot find out what happened to her. For those who stayed, they probably could keep their feudal positions with the landlord since they really needed the farmers.

I think my tenement reading is now finished. That was a wee bit too much for me. I started with Jacob Riis' book and also read quite a bit on the net, and said....that's enough of that.

'The Great Irish Potato Famine'? If I recall rightly, that one was just as shocking in the detail, but it was a little more layered under statistics than Woodham-Smith.

I do recall looking at lists of figures and not quite seeing the picture. Then I let my mind wonder onto what these figures actually represented. In some ways, that was worse than Woodham-Smith spelling it out.

Simple maths does tell most of a picture there, but we still have to be careful not to assign it all to starvation. Just because there's a huge genocide going on, it doesn't mean that people aren't also dying in unrelated ways. Much smaller numbers, obviously, but nevertheless there.

Plus there were the devastating pandemics that accompanied the potato blight. Those in, say Antrim, were more likely to have died of typhus or cholera during this time.

There are also those dying on the coffin ships. The emigration figures tend to look at those who arrived, not those who left. The latter was a much bigger number!

No-one can ever say that the Irish population wasn't horrifically hit though. Even today, their numbers haven't quite recovered; and the demographics were utterly changed.

I'm familiar with the situation in the New York tenements too. May I recommend 'Five Points' by Tyler Anbinder for more information about that?

Harrington was/is a big surname in Ireland, but comes from two roots. One is an English plantation family, who were landowners and probably not people that either of us hope to be related to. The other comes from Anglocizing a Gaelic surname that was prevalent in the Cork area. They actually were Irish. :)

I'm reading Donnelly's book now. I'm a tad over the shock I experienced when reading Woodham-Smith. I get frustrated when I read low stats of how many perished. 9 million were alive in 1841, 4 million remained, and 1 1/2 million emigrated. Simple math that nobody can seem to do. Nor will we ever know the real numbers.

BTW, I have a Harrington in my tree. Have you read about the tenements in New York? It's the stuff they make movies out of. Doing family research can be an eye-opener.

The Irish coming from the worst conditions in the world wound up in the next to worst conditions in the world upon arrival here. It's been some journey for me, especially when I can put names to the people who suffered so much. Not all them though. Just one limb of the tree, the others landed softer.

Cecil Woodham-Smith's 'The Great Hunger' owned my world, when I first started researching this period in history. My history lecturer had to step in and remind me that you did need to refer to several texts, not just rely on one source. LOL

I agree that it's not for the faint of heart. It's a downright devastating testimony to what happened then.

It's horrific that any country should know the meaning of marasmus, except in an historical context. Unfortunately, way too many still do.

As your family were Catholic, I'm going to assume that they didn't buy their way out of the genocide. Their story is certainly one worth uncovering.

They were all Irish Catholics, so no help there for them. The book that I read, authored by Cecil Woodham-Smith, was a real eye opener. It's not for the faint of heart. She spent 10 years researching and found quite a bit of correspondence between all the parties involved.

After reading her book, I came away feeling and knowing more could have been done to save them. I learned a new word from all this reading...marasmus. It's an almost forgotten word now in our part of the world. Not in others.

The first thing that I'd say is that it could have been geographical. The famine was very widespread, but not completely so. It may have been that your ancestors lived in one of the lucky pockets of Ireland which largely escaped the famine.

They may also have been rich. Only the potato crops were blighted, there was other food in Eire at the time. The majority of it was being sent to England, under a military escort; but the wealthy Irish (usually Protestant Anglo-Irish) could afford to eat.

Otherwise, you are looking at a massive struggle. Your people could have been kept barely alive under the work programs, or through charitable organizations. They might have managed to keep hold of their fishing equipment and eaten fish. They could have used wild, edible plants. There are a myriad of individual stories of survival here, but none are pleasant to explore.

It is a very dark time in Ireland's history.

There must be two stories of the famine going on at the same time. The survivors who stayed after 1850. How did they survive? I have Ggrandparents who left in 1850, and another set who were born in 1850 and the family didn't emigrate till the mid 1860's. Why would one survive and thrive, and the other lose everything including three kids?

It's hard to read the books on the famine. Especially since I know now it was the story of my family who had to manage each day to find something to eat.

That's very true and a poignant quotation there from Rabbie Burns.

I'm glad that you found it informative. This was not a shining moment on the part of the British; and the Irish are still recovering from this devastation, especially in terms of population and language.