As soon as the daguerreotype was invented in 1839, families began to take photographs of their dead. It quickly became viewed as a respectful part of the funeral ritual; and a powerful aid to mourning.

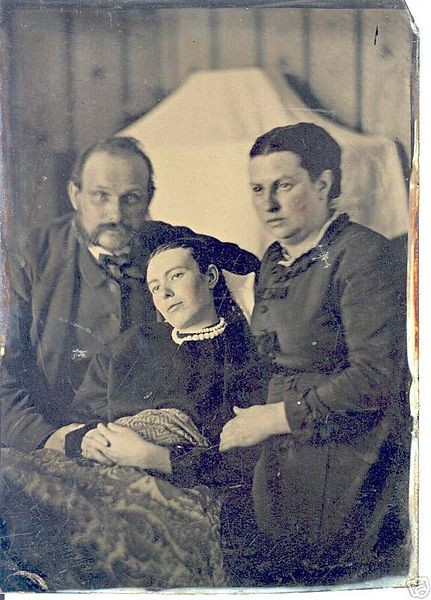

Until the latter part of the 19th century, the most common practice was to make the deceased appear as in life. They would be propped up by a hidden stand, or arranged on a chair. Children were usually laid out on a bed, as if they were merely asleep.

In order to aid this illusion, living family members and/or pets would pose with them. They would try desperately to keep the grief from their features. It would not do to give the game away.

However, as the decades went on, it was seen as more proper to give hints to the true status of the dead. Flowers covered beds, in elaborate tableaux, that could not be mistaken for a night's repose.

By the end of the 19th century, coffins were brought into view; or the deceased were pictured as they were, with no attempt made to arrange them in life-like positions.

After that, the practice slipped out of commonplace in Western society. It still did go on, but more rarely, until the fashion went away completely. Then it became taboo.

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Comments

It makes perfect sense, especially if there would never be another photo. Consider how we now take pictures of infants who are stillborn or pass soon after birth.... An image of a lost loved one is a powerful grieving tool... And a remembrance. If we had no other options, no other photos, I'm sure we would do the same thing today.....

Thank you, I'm glad you enjoyed it. This is why I love history so much. There are so many weird and wonderful stories.

Good information, I had never heard of this before

It's an unusual thing to do nowadays, but I don't think it's wrong. In some ways, it can be closure or a momento. It may also be a psychological thing. You can distance yourself from the reality by looking at it through a lens. Then you can learn to accept it in your own time, using the photograph to reaffirm that this incomprehensible thing (a death in the family) actually did happen.

After all of the family had left, my uncle returned and photographed my grandfather in the funeral home. (I don't think the rest of the family was really aware of what was going on but being a curious child with big ears...I knew) At 10, I didn't think this was odd, nor do I now. I can see how back then, it may have been a part of "closure" or the grieving process. If the loved one looked "peaceful" the photo may have brought comfort especially if the person had suffered during the end stages of life. I enjoyed your article...very interesting.

That is such a beautiful comment and very thought-provoking. I love that you practice post-mortem photography today too. Perhaps if more of us did, we wouldn't be so frightened by an inevitable end to life.

Hi Ember! It sounds to me like your parents had a really healthy approach to explaining death and encouraging questions.

I don't think you were alone in the type of questions either. I cringe now recalling some of the questions that my brother and I asked my Nan, the winter after my Grandad had died. Like 'is he cold in the ground?' and 'is he all bones now?' I remember my mortified mother telling us off for it, but can't picture my Nan's reaction. I think she was very dignified about it, else I really would have it lodged in my memory.

Taboo or unfashionable? You make some great points here. i know that forensics investigators and mortuary personal often still have to photograph corpses. They have a purpose and no qualms.

But would you feel confident requesting a photograph like the Victorian ones, if a member of your family died? How would you feel if a relative turned up to the death-bed with a camera? I think that would be incredibly awkward, hence my feeling that it's more taboo than unfashionable there.

Or perhaps the unfashionable nature means that we don't automatically know the etiquette, hence we shy away. You've given me plenty to think about here!

OH. And, I wrote you a comment last night but I guess I didn't post it properly, and I lost it. :C But I was wondering if it isn't so much a taboo as it just no longer serves its purpose, so it fell out of fashion. I think it's not as taboo as it really might seem at first, because when you consider the people in society today who are in the same place as many of these families might have been, I think a lot of times they do chose to take pictures. Back then, with the accessibility of photography being so low, that picture may be the only ones they have of their lost loved one, so it is a really good memento. If you think about it, most commonly the only families today that didn't have a chance to get a photograph of a family member or loved one, it is probably with a baby that was born really ill, and died soon after birth. And it isn't uncommon for the families of that child to take a picture with him or her, if they hadn't gotten one yet. And, I think, like if my sister or father passed away and I literally had no other photo of either, I know I would want a picture...And as perhaps as off-putting as the idea may come across at first, I think considering that, no one would think of me as incredibly creepy or look down on me. But because most families do have pictures, there isn't a need for such a practice. I dunno, it was a thought.

Sorry for multiple long comments :D

This was a really captivating article. I was reading it last night with Kenna, and she was really inspired by it and took off to write. I think it is beautiful and sad.

I agree that death doesn't get the respect it deserves. My mom was always really blunt with me about things I'd have to face in life, and death was one of them. It was a cat that died that sparked the conversation, and we buried it, and my mom explained death, how unexpected it can be, how everyone is going to die including her, my brothers, me, but how it isn't something I should spend my time worrying over. She let me ask whatever questions I wanted, and I came to understand and be quite comfortable with the fact that death is just as much a part of life as life itself is...But, my poor mom did get quite the disgusted looks from other parents, when I'd suddenly start popping off with another round of questions... you know, in the grocery store and the like, because they were things like "What would you look like dead?" "What would you feel like?" --and in response to the explanation to that one, I asked if a dead person was as cold as frozen peas. I was a delightful five-year-old.

When grass grew back over where we'd dug up a hole to bury the cat that had died, I remember I wanted to dig her up, as with most children the permanence of her departure was something I just couldn't grasp. My mom explained decomposition and how all we would find, if anything, was her bones. My dad told me how decomposing things gave nutrients to dirt that let plants grow. That put in my mind that my cat was now the grass that had grown. From that stemmed a Pocahontas-like understanding of nature. Everything was A LIVING THING. (Oh, and then my dad was like, yeah plants are alive, and I was like yesssssssssssss! Cue my love for nature, directly tied to my childlike fascination with death). I came to view death as a powerful force, which in truth awed me. My understanding of life and death changed as I grew, and interestingly enough the first time I feared death was when I was 8/9 ish when we first starting to go to church...

It still does evoke a full-range of emotion from me, from awe to fear, and definitely respect. My mom's choice may have been less-than-typical, but I personally don't see anything wrong with it.

Infant mortality was so high during the Victorian era that it was a rare parent who didn't lose at least one. I've seen some truly heart-breaking memorials, like one in Haworth, Yorkshire, where 12 infants were lost. None of them had made it past five, with the majority dying in the first year.

The quantity might have been remarkable, but the ages of the deceased children weren't.

I've read healthcare and parenting guidance from the period, which recommended that you didn't try to bound with your baby (nor really consider it a real thinking, feeling person) until at least one years of age. It was for this very reason.

My heart goes out to them too.