The Hancock farmhouse no longer stands, but those seven graves still do.

You can just discern a patch of darker ground where the house should be. The walled graveyard would have been practically on the doorstep. The agreement that the people of Eyam made in 1666 was that they would not flee, and they would bury their own dead in land made hallowed by their sacrifice.

Elizabeth Hancock did just that. She cared for her family, then single-handedly dug their graves.

It's difficult to imagine what she went through. Her children must have started with the fever and open sores by August 1st.

On August 3rd 1666, she buried seven year old Elizabeth and five year old John. It can hardly be expected that she had help from her husband, as he would have already been sickening himself by then.

On August 3rd 1666, she buried seven year old Elizabeth and five year old John. It can hardly be expected that she had help from her husband, as he would have already been sickening himself by then.

John Hancock died on August 7th 1666. His wife, stupefied with mourning her earlier losses, had to contend with both that and the death of two more children. Sixteen year old William and three year old Oner went with their father into the Riley graves.

Still there was no respite, because by now the two remaining daughters had begun showing symptoms of plague.

Fourteen year old Alice died on August 9th. Her nine year old sister Anne followed the next day.

The Riley Field was so high up and exposed, that the villagers in Stoney Middleton would have been able to observe Elizabeth's desperate plight. But they couldn't help her. To do so would be to undo all the sacrifices that the people of Eyam had made. The plague would simply have spread.

No doubt Elizabeth Hancock was in some degree of shock by now. The Black Death is not an easy nor pretty way to die. She had tended those she loved dearest through it all, then consigned them to the ground.

But she didn't stop there. Back over on the Talbot farm, seventy-eight year old Bridget fell to the plague too. The baby was alone, so Elizabeth brought her back to her home. The ad hoc adoption didn't last long. Within days, the Black Death had taken the infant too.

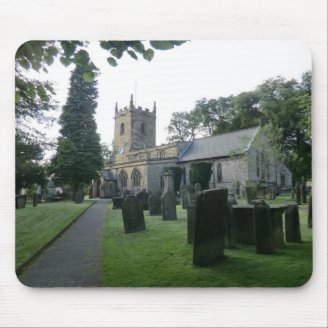

It is easy to imagine the 17th century in this place. So little has changed.

It is easy to imagine the 17th century in this place. So little has changed.

On August 3rd 1666, she buried seven year old Elizabeth and five year old John. It can hardly be expected that she had help from her husband, as he would have already been sickening himself by then.

On August 3rd 1666, she buried seven year old Elizabeth and five year old John. It can hardly be expected that she had help from her husband, as he would have already been sickening himself by then.

Being up at the Riley graves helps contextualize Eyam's history, like nothing down in the village could do.

Being up at the Riley graves helps contextualize Eyam's history, like nothing down in the village could do.

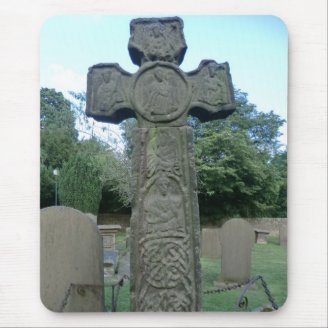

There has been a church on this spot since Saxon times. An 8th century Celtic cross in the grounds attests to the presence of Christianity even earlier.

There has been a church on this spot since Saxon times. An 8th century Celtic cross in the grounds attests to the presence of Christianity even earlier.

Despite what you may have read in Geraldine Brooks's

Despite what you may have read in Geraldine Brooks's

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Comments

Then my job has been done here. It's worth going there to walk them for yourself too. Eyam is a fascinating village to visit.

Excellent article Jo, easy to imagine walking the same steps along with you!

no u and gtfo meh article!!1!!

stfu

I'm glad to have made history come alive for you. :D These were real people, just as you and I, that's the most important thing to remember, when hearing the historical stories.

I have massive respect for Elizabeth Hancock. I can't imagine having to go through that.

The story of Elizabeth Hancock is incredible, and you told it so well. And then the quarantine. Your article makes one more interested in actually looking at stories unfolding in various families since the Middle Ages. Nice work! I really enjoyed it.

I wasn't sad, just fascinated and in awe of the villagers, right up until I went to the Riley graves. Then the reality hit me and, yes, that was upsetting.

Another place for your itinerary, when you tour Britain? I'll come too!

Beautiful place. I'd love to visit. And what a history!

Many people did. She wasn't unique by any stretch in Eyam at the time. I was quite struck, walking around, how many plaques showed a sole survivor. It was usually the mother of the family, though it couldn't be a gender thing, as so many adult daughters died too. It was noticeable enough that my friend and I were pondering on why later on.

But since coming home, I've studied the historical population records for the time. It wasn't just the women that this happened to. It's just coincidental that so many plaques (and the Riley Graves) had that scenario. There were just as many houses where the sole survivor was male.

Apparently the phenomenon has been subject to debate amongst scientists. It appears that some people have a natural immunity to bubonic plague. There are others who had already contracted it in childhood and recovered. This also immunized them against this outbreak. Death was likely for those who got it in 1665-1666, but there was a slim chance of survival too. That did happen.

A few years ago, there was DNA testing amongst those residents of Eyam, who could trace their ancestry back to the village in the 17th century. These were obviously the descendents of survivors. It was found that they had an above average genetic mutation called CCR5-Delta 32. This would probably leave them immune in another outbreak. It's highly likely that Elizabeth Hancock had the strain, but unfortunately hadn't passed it onto any of her children. (http://www.eyammuseum.demon.co.uk/DEL...)

Sorry, I went off on one, but this whole subject is really fascinating me right now! I'm glad that it interested you too. Thank you for reading.