Alston, Diane G., Shawn Olsen, and James Barnhill. “Corn Earworm (Helicoverpa zea (Boddie).” Utah Pests Fact Sheet, ENT-156-98. December 2011. Utah State University Cooperative Extension. Web. extension.usu.edu

- Available at: http://extension.usu.edu/?search=corn+earworms&searchType=2

Boisduval, Jean Alphonse, and John LeConte. Histoire générale et iconographie des lépidoptères et des chenilles de l'Amérique Septentrionale. Paris: Roret, 1833.

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/38244

- Available via BnF Gallica at: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k9619554m/f1.item.texteImage

- Available via Internet Archive at: https://archive.org/details/histoiregnra00bois

"Broad-tailed Hummingbird Selasphorus platycercus." World Bird Info > Birds Search > Scientific Name. John Penhallurick. Web. worldbirdinfo.net

- Available at: http://worldbirdinfo.net/Pages/BirdCitationView.aspx?BirdID=34834

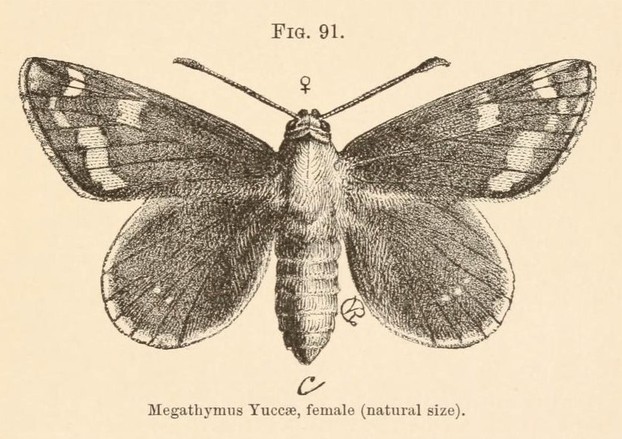

Calhoun, John V. "Notes on Megathymus yuccae as Illustrated by Boisduval & LeConte ([1837]), with Remarks about the Holotype of M. cofaqui." News of the Lepidopterists' Society, Vol. 54, No. 1 (2012): 8-13.

- Available via Butterflies of America at: http://butterfliesofamerica.com/megathymus_y_yuccae.htm

- Available via ResearchGate at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337544941_From_Oak_Woods_and_Swamps_The_Butterflies_Recorded_in_Georgia_by_John_Abbot_1751-C1840_Based_on_His_Drawings_and_Specimens

Christman, Steve. "Yucca filamentosa." Floridata > Plant Profile List. Last updated 09/17/03. Floridata.com: Jack Scheper. Web. www.floridata.com

- http://www.floridata.com/ref/y/yucc_fil.cfm

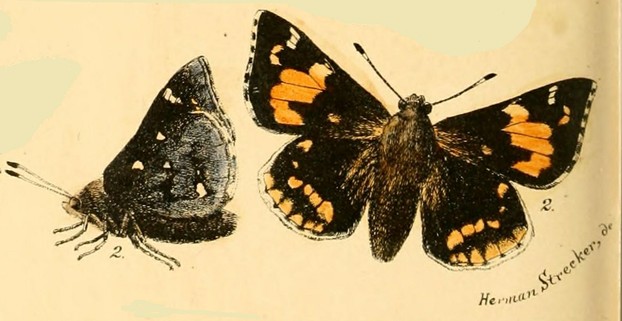

"Cofaqui Giant-Skipper Megathymus cofaqui (Strecker, 1876)." Butterflies and Moths of North America. Butterfly and Moth Information Network, Kelly Lotts and Thomas Naberhaus. Web. www.butterfliesandmoths.org

- Available at: http://www.butterfliesandmoths.org/species/Megathymus-cofaqui

Daniels, Jaret C. Yucca Giant-Skipper Butterfly, Megathymus yuccae (Boisduval & Leconte) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae). IFAS Publication Number EENY-427. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, 2009.

- Available at: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/in800

Flora: A Gardener’s Encyclopedia. Volume II: L-Z. Portland OR: Timber Press, 2003.

French, G. (George). H. (Hazen). The Butterflies of the Eastern United States. For the Use of Classes in Zoology and Private Students. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co., 1886.

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/979891

- Available via Internet Archive at: https://archive.org/details/butterfliesofeas00fren/

Garrett, J.T. The Cherokee Herbal: Native Plant Medicine from the Four Directions. Rochester VT: Bear & Co., 2003.

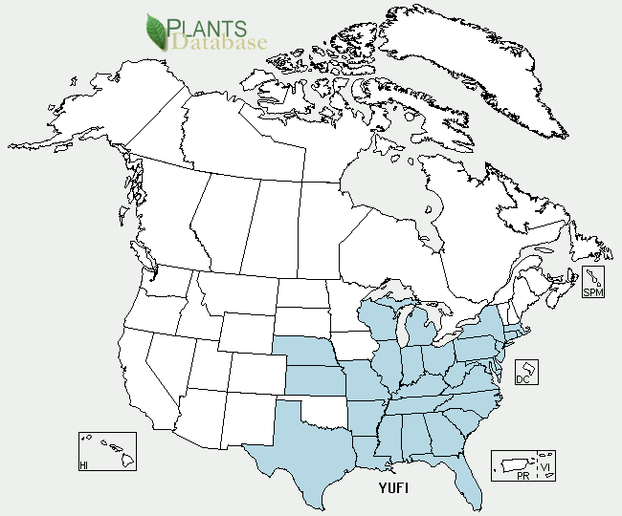

Immel, Diana L. "Adam's Needle, Yucca filamentosa L." U.S.D.A. PLANTS Database > Plant Guide. U.S.D.A. Natural Resources Conservation Service Plant Data Center. Edited September 27, 2001. Web. plants.usda.gov

- Available via USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service Fact Sheets and Plant Guides at: http://plants.usda.gov/java/factSheet

Kerner von Marilaun, Anton. The Natural History of Plants: Their Forms, Growth, Reproduction, and Distribution. Volume II: The History of Plants. Translated and Edited by F.W. Oliver. With the Assistance of Marian Busk and Mary F. Ewart. London, Glasgow and Dublin: Blackie & Son, Ltd., 1902.

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/ia/cu31924024757746

- Available via Internet Archive at: http://archive.org/details/cu31924024757746

Loewer, H. Peter. The Evening Garden: Flowers and Fragrance from Dusk Till Dawn. Portland OR: Timber Press, 1993.

Lovell, John H. The Flower and the Bee: Plant Life and Pollination. Illustrated from Photographs by the Author. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1918.

- Available via Internet Archive at: http://archive.org/details/flowerbeeplant00love

Mails, Thomas E. The Cherokee People: The Story of the Cherokees from Earliest Origins to Contemporary Times. Tulsa OK: Council Oak Books, 1992.

Missouri Botanical Garden. First Annual Report of the Director, for 1889. St. Louis, MO: Board of Trustees of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 1890.

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/15206

Moerman, Daniel E. Native American Ethnobotany. Portland OR: Timber Press, 1998.

Moerman, Daniel. Native American Medicinal Plants: An Ethnobotanical Dictionary. Portland OR: Timber Press, 2009.

Moisset, Beatriz. “Yucca Moths (Tegeticula sp.).” Celebrating Wildflowers > Pollinators > Pollinator of the Month. U.S. Forest Service. Web. www.fs.fed.us

- Available at: http://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/pollinators/pollinator-of-themonth/yucca_moths.shtml

Ortho's All About Attracting Hummingbirds and Butterflies. Des Moines IA: Meredith Books, 2001.

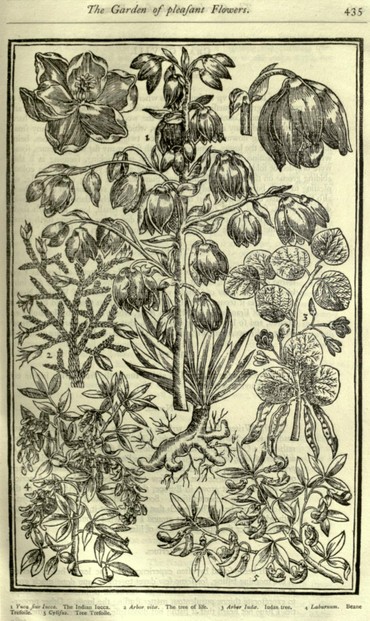

Parkinson, John. Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris. Faithfully Reprinted from the Edition of 1629. London: Methuen & Co., 1904.

- Available via Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/paradisiinsolepa00parkrich

Rau, Phil. “The Yucca Plant, Yucca filamentosa, and the Yucca Moth, Tegeticula (Pronuba) yuccasella Riley: An Ecologico-Behavior Study.” Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, Vol. 32, No. 4 (November 1945): 373-394.

Redouté, Pierre Joseph. Les Liliacées. Tome cinquième. Paris: L'Imprimerie de Didot Jeune, 1809.

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/300094

- Available via Internet Archive at: http://archive.org/details/mobot31753002806708

Riley, Charles V. "The Yucca Moth and Yucca Pollination." Popular Science Monthly, Vol. XLI (June 1892): 171-182. Also in: Missouri Botanical Garden Third Annual Report (1892): 99-158.

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/675320

Roth, Sally. Attracting Butterflies & Hummingbirds to Your Backyard. Rodale Organic Gardening Book. Emmaus PA: Rodale, 2001.

Skinner, Henry. "Pupal Differences in Megathymus (Lep.)." Entomological News, Vol. xxviii, No. 5 (May 1917): 232.

Strecker, Herman. "Description of a New Species of Aegiale and Notes on Some Other Species of North American Lepidoptera." Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, Vol. XXVIII (1876): 148-153.

- Available via Internet Archive at: https://archive.org/details/proceedingsofaca28acad

Strecker, Herman. Lepidoptera Rhopaloceres and Heteroceres, Indigenous and Exotic, with Descriptions and Colored Illustrations. Reading, PA: Owen’s Steam Book & Job Printing Office, 1872.

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/40156

- Available via Internet Archive at: http://archive.org/details/lepidopterarhopa00stre

Swainson, William. A Selection of the Birds of Brazil and Mexico. London: Henry G. Bohn, 1841.

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: http://biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/49941#/summary

“The Yucca Cactus and Yucca Moth: A Perfect Example of Co-Evolution.” National Biological Information Infrastructure > Ecological Topics: Pollinators. U.S. Geological Survey Biological Informatics Program. Web. www.nbii.gov

- Available at: http://www.nbii.gov/portal/server.pt/community/butterflies_and_moths/856/yucca_moths/4933

Trelease, William. "Notes and Observations. 1. Detail Illustrations of Yucca." Missouri Botanical Garden Third Annual Report (1892): 159-166.

- Available via Biodiversity Heritage Library at: http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/675521

Witthoft, John. “The Cherokee green corn medicine and the green corn festival.” Journal of Washington Academy of Sciences, Vol. 36 (July 1946): 213-219.

"Yucca Giant-Skipper Megathymus yuccae (Boisduval & Leconte, [1837])." Butterflies and Moths of North America. Butterfly and Moth Information Network, Kelly Lotts and Thomas Naberhaus. Web. www.butterfliesandmoths.org

- Available at: http://www.butterfliesandmoths.org/species/Megathymus-yuccae

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Are Hawaiian Huakai Po Nightmarchers Avenging Halloween Thursday?on 10/02/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 15, 2024, Due Dateon 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2023 Forms 1040 and 1040SR Filed in 2024on 04/15/2024

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Mailing Addresses for 2022 Form 4868 Extending 1040 and 1040SR April 18, 2023, Due Dateon 04/13/2023

Comments

WriterArtist, Yucca filamentosa is definitely a beautiful plant! It's a treat to find Magnolias with Y. filamentosa nearby, and both in full bloom.

Me, too, I love Yucca filamentosa. It seems to grow and bloom overnight!

Yucca filamentosa seems similar to the lovely magnolia blooms. The images are beautiful and the details are great. Love this beautiful plant.