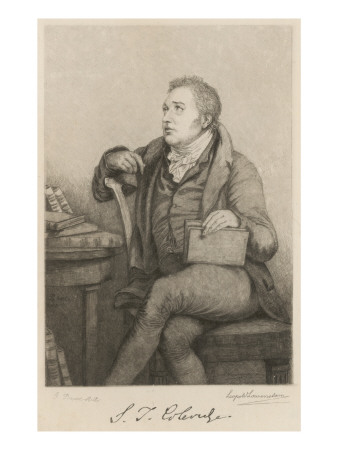

If Byron's Fragment of a Novel was the grandfather of the whole vampire genre, then Christabel was its grandmother. Yet the last thing that Coleridge wanted at that moment was to have another idea stolen from him. Christabel had already been plagiarized enough.

With Lord Byron's assistance, the unfinished stanzas were published within months. In May 1816, the first preface to Christabel made blatant all of Coleridge's frustrations and fears. He hoped that the reading public would not accuse him of having stolen anything about the poem, but he couldn't fault them if they did.

Coleridge began by clarifying that the first part had been written in 1797, with the second following in 1800. He went on to state,

'It is probable, that if the poem had been finished at either of the former periods, or if even the first and second part had been published in the year 1800, the impression of its originality would have been much greater than I dare at present expect. But for this, I have only my own indolence to blame.'

He continued to defend himself against possible claims of plagiarism, yet he intriguingly omitted the names involved.

Unlike his contemporary readers, we have the correspondence between Coleridge and Byron from 1815-1816. We know what was going on. Coleridge had shown his half-completed poem to William Wordsworth, who had promptly stolen its unusual meter (four beats to a line, rather than the more common syllable based poetic rhythm). He had also let Sir Walter Scott read it. Coleridge had since heard reports of Scott traveling around the Continent, reciting the poem in public readings, as if it was his own.

Lord Byron calmly read the complaints, then requested a copy of the stanzas himself. It duly arrived in October 1815.

A lot of Coleridge's poetry was included in the telling of ghost stories, during that wild week in Villa Diodati. (Mary Shelley mentioned The Rime of the Ancient Mariner twice in Frankenstein.) The turn of Christabel came shortly after midnight, when Byron read it aloud to his drug-addled guests. When it was left on an unresolved cliff-hanger, the idea came for them all to write stories of their own.

Christabel's Gothic themes informed Byron's Fragment of a Novel, then John Polidori's The Vampyre in its turn. All they really did was change the noble ladies into gentlemen on a Grand Tour of Europe. It was Coleridge who had already had the idea to make his vampire no Eastern European peasant, but a member of the aristocracy.

And it was Coleridge who, feeling that he was the victim of a real life vampire, turned that into stanzas for a poem. Then watched helplessly as others fed on the very life of that poem. The world was ready for a new monster, and if anyone lit the fuse for the subsequent explosion of vampiric literature, then it was Coleridge.

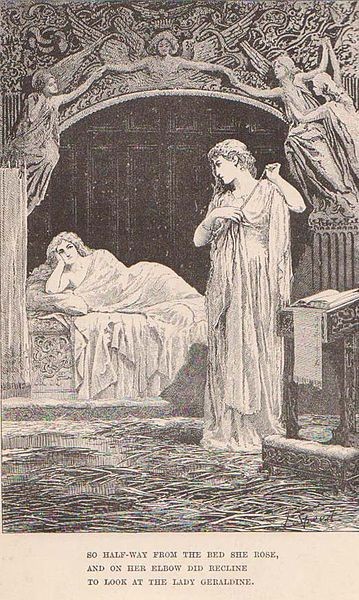

It's never once stated that Geraldine was a vampire. But Samuel Taylor Coleridge never completed his poem. He never reached the great reveal. But the old, well-worn tropes are all here. Many of them were heard for the first time in these verses.

It's never once stated that Geraldine was a vampire. But Samuel Taylor Coleridge never completed his poem. He never reached the great reveal. But the old, well-worn tropes are all here. Many of them were heard for the first time in these verses.

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Comments

LOL I like your version too.

But we do know about Wordsworth. Coleridge told us so.

Blood, blood everywhere, nor any drop to suck? Wordsworth wasn't a vampire. I think we would have known about it by now if he was.

LOL! I see what you did there. Clever! I'm guessing that you're going on the basis that Wordsworth wasn't a vampire then.

Daffodils, daffodils everywhere, nor any vampires to see!

Opium, opium everywhere, nor any sense to think. ;) Yes, he was quite the junkie. Most of the Romantic poets were.

I didn't know Coleridge was drug addict.