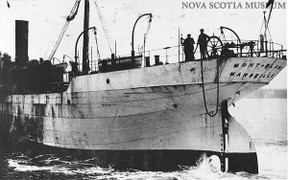

There's been a sneaking suspicion over the years that the crew of the SS Mont-Blanc just didn't try hard enough to put out its deck fire. That with a bit more effort, and a lot less cowardice, the Halifax Explosion could have been averted.

There's been a sneaking suspicion over the years that the crew of the SS Mont-Blanc just didn't try hard enough to put out its deck fire. That with a bit more effort, and a lot less cowardice, the Halifax Explosion could have been averted.

But a whole team of professionals did try and failed.

From the instant that flames were spotted on board, the 'Box 83' bell sounded in the docks. This was the signal for Halifax's fire fighters to drop what they were doing and prepare to respond to the emergency.

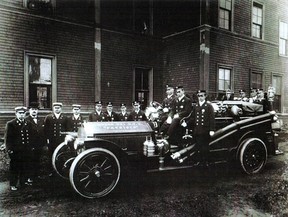

In 1917, being a member of the fire brigade was not a full time occupation. Trained volunteers left their ordinary workplaces and waited in pre-arranged places to leap onto Patricia, as she passed. Patricia was something special for Halifax. She was Canada's first fire engine and she served their city.

Painter and fire fighter Albert Brunt was humiliated that morning. He'd abandoned his trolley, laden with brushes and paint, at the first urgent peal of the Box 83 bell. Waiting on the corner of Gottingen Street, he'd stood poised as Patricia screamed down the street. He leapt, and missed. His colleagues were all jeering at him, as the fire engine went on without him.

He was not nearly as embarrassed as the unnamed fire fighter who, suffering from flu, had been throwing up in the West Street Station's toilet when the alarm sounded. He'd not been able to extract himself in time to climb onto Patricia while she was stationary.

Once on Pier 6, the ten strong Halifax Fire Department were joined by another brigade from Brunswick Street, who arrived in Chief Edward Condon's Buick. He took one look at the blaze and rang the dockyard bell again. More local fire fighters arrived, including retired Johnny Spruin, a respected veteran who brought his own water pump on a horse drawn carriage.

Overlooking them all was Constant Upham, the owner of the North End General Store. He was one of the few people in Halifax with a telephone and, discerning that this wasn't your average ship fire, he took it upon himself to call every fire station in the city.

Those too far away to have heard the bell now sounded their own. Fire personnel poured in from all four local brigades. They faced a blaze so intense that they couldn't even look directly at it. Nevertheless their hoses remained firmly trained on the raging inferno. It made no difference. The ship's fire could not be extinguished, even drenched consistently by the city's most powerful hoses.

All but Patricia's driver Billy Wells were killed when the SS Mont-Blanc exploded. The horses too.

Afterwards, there were only thirty trained fire-fighters left in the whole of Halifax, including Albert Brunt and his ill colleague. They were confronted by thousands of fires springing up throughout the ruined city and no chief left to lead them. Their ranks were swollen by 120 survivor volunteers, and they did their best.

It's difficult for any of us to know for certain what we would do in an emergency.

It's difficult for any of us to know for certain what we would do in an emergency.

When any ship is ablaze, the priority is to stifle the flames. When it's a munitions ship, that becomes even more urgent.

When any ship is ablaze, the priority is to stifle the flames. When it's a munitions ship, that becomes even more urgent.

There's been a sneaking suspicion over the years that the crew of the SS Mont-Blanc just didn't try hard enough to put out its deck fire. That with a bit more effort, and a lot less cowardice, the Halifax Explosion could have been averted.

There's been a sneaking suspicion over the years that the crew of the SS Mont-Blanc just didn't try hard enough to put out its deck fire. That with a bit more effort, and a lot less cowardice, the Halifax Explosion could have been averted.

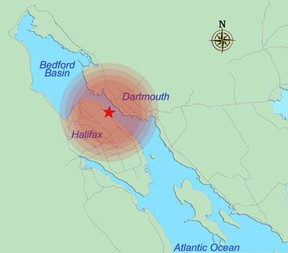

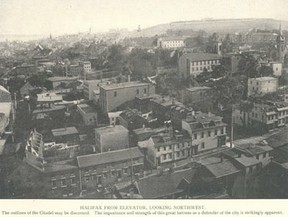

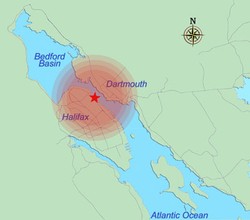

There was no saving the SS Mont-Blanc before she exploded. But the sheer scale of the catastrophe was dictated by where the blast occurred.

There was no saving the SS Mont-Blanc before she exploded. But the sheer scale of the catastrophe was dictated by where the blast occurred.

If it was inevitable that the inextinguishable SS Mont-Blanc would explode, and it could not be towed away in time, then the obvious third solution would be to clear the blast site. That is a lot easier said than done.

If it was inevitable that the inextinguishable SS Mont-Blanc would explode, and it could not be towed away in time, then the obvious third solution would be to clear the blast site. That is a lot easier said than done.

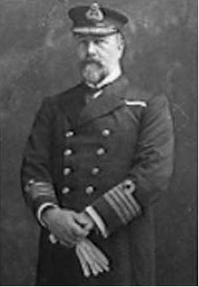

Dockyard Superintendent Captain Edward Harrington Martin was away in England at the time of the Halifax Disaster.

Dockyard Superintendent Captain Edward Harrington Martin was away in England at the time of the Halifax Disaster.

Mate Terrence Freeman RNCVR was aware that there were explosives on board the blazing munitions ship. But he wasn't at his desk, nor even on dry land.

Mate Terrence Freeman RNCVR was aware that there were explosives on board the blazing munitions ship. But he wasn't at his desk, nor even on dry land.

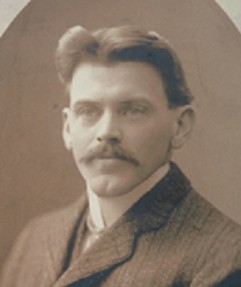

Freeman's overall superior was RCN Commander Frederick Evan Wyatt.

Freeman's overall superior was RCN Commander Frederick Evan Wyatt. At the foot of Richmond Street, in the rail master's yard, sat the telegraph dispatch office of the Canadian Government Railway. The tiny wooden shack was surrounded by freight storage space and tracks. It afforded the two men inside a clear view of the harbor.

At the foot of Richmond Street, in the rail master's yard, sat the telegraph dispatch office of the Canadian Government Railway. The tiny wooden shack was surrounded by freight storage space and tracks. It afforded the two men inside a clear view of the harbor.

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Comments

I just happened to revisit this web page after 2 years. I certainly did not mean to sound high-handed regarding the errors in your posts. However, as the author of this page, the onus is on you to present viable sources other than simply showing the books and websites that your information may have come from. By now, you may have read my book Scapegoat, the extraordinary legal proceedings following the 1917 Halifax Explosion. My extensive notes and bibliography address many of the detailed primary sources for the majority of my comments you questioned in your rebuttal. In addition to those pointed out, there still exists no definitive evidence that the Vince Coleman story occurred as you describe. As a matter of fact, the evidence from the Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry as well as eye witness accounts of people on the train itself and at Rockingham Station puts into question much of the story surrounding the myth. Being willing to examine details to the nth degree is what any good research is all about. It is also important not to let a good story stand in the way of the facts.

2/2

I do hope you'll forgive my rebuttal. It would be so much easier - and desirable - for me to simply make any amendments. I do wish to have the most accurate historical record that I can produce, otherwise what's the point? But I have no guarantee that you're even the author that you claim to be.

I've written an article based on a week long survey of primary and secondary sources, and - with all due respect - you're someone who's merely written a comment without citing any sources. Naturally I'm going to double-check anything before incorporating it.

I do thank you for correcting the date on the Mackey interview though. I'd read a transcript, where someone had scribbled 1967 on top. You're quite right, it was 1958.

I'm happy to have included your YouTube lecture. I found it interesting when I watched it as part of my research for this series. I do hope you will list your book 'Scapegoat' on Amazon though, so I can add it to the book module here.

Despite your rather high-handed denunciation of my work as having 'too many errors to mention', I was still grateful for your corrections. (I count an accurate rendering of events for my readers above my pride.) Until I came to make the amendments. Then I found myself quite flabbergasted.

The majority of what you've written is either stated already in the narrative, or contradicts the historical/scientific record elsewhere.

For example, I've written that Wyatt 'served as a member of the British Royal Naval Reserve, before relocating to Halifax. When the Great War was declared, Wyatt enlisted in the Royal Canadian Navy.' You claim that's in error, as he was a retired RNR officer, who was assigned to the RCN in 1917. The only difference is that you've used acronyms, and I've spelled it out.

Another example, I've stated that Mackey tried but failed to communicate with Stella Maris. The noise was too loud for him to be heard by Captain Brennan. You've listed that as being in error, as Mackey had no verbal communication with the tugboat's captain. Can you see my confusion on what precisely you're calling me out on here?

Then again, you've said that we can't be certain of the time-frame. It was approximately 20 minutes. But we can be quite approximate. We know from harbor records that the ships collided at 8.45am. Geophysicists have determined the precise time that the explosion occurred: http://www.cbc.ca/archives/categories...

At best, you are quibbling over 25 seconds. Had it been a few seconds either way, it would not affect the series of events.

1/2

I appreciate being mentioned on your website but I would be remiss if I were not to point out a few of the historical errors in your essay the least of which is the date of Francis Mackey's CBC interview. It took place in1958 not 1967. Mackey died in 1961.

There are too many errors to mention but some of the stand-outs are as follows: Acting Commander F. Evan Wyatt was a retired R. N. R. officer assigned to the RCN. Le Medec and Mackay were arrested and charged with manslaughter and criminal negligence following the inquiry. Le Medec did not return to France until after the preliminary hearing. He and Mackey were released on a writ habeas corpus. Wyatt went to trial but was acquitted. The accepted timeframe between the collision and the explosion was not definite - approximately 20 minutes. Francis Mackey never had any vocal communication with the Stella Maris. The tug had no fire-fighting equipment to speak of and had no intention of towing Mont Blanc to sea or anywhere else. They just wanted to move the ship's burning stern away from Pier 6. Henry Dustan's office was not at the North Street Station. Wyatt did not simply suspect there were explosives aboard Mont Blanc - he knew of the TNT though not the picric acid or guncotton. There was never any preposterous perception or suggestion by anyone - ever - that Commander Wyatt ran away from anything. Lieutenant James Anderson Murray was on the telephone with Acting Captain James Turnbull at the Port Convoy Office at the time of the explosion. Murray died in his office. It was not Commander Wyatt's job to arrange for convoys.

Ah! I noticed that earlier, then got side-tracked before doing something about it. I'm on the case now.

Yippee. something to keep me going through another day of cut-paste-proofread. Can you please delete that first comment of mine, by the way? I appear to have double double posted posted.

That Dockyard Super looks quite like my cousin too. I didn't think much of it, when i first saw his name, as Harrington isn't that rare. But that likeness upped the stakes a little more.

I started part 3 today, but didn't finish it. It should be along tomorrow. :)

You should check the family tree. That Dockyard Super could be related to you. And hurry up with part 3 already! I'm hooked...

You're welcome. A Canadian friend mentioned it to me a few weeks ago and I was stunned that I hadn't heard about it before. You'd think that something like this would be on world-wide history curricula.

I don't think I know anyone from Halifax, but I can certainly vouch for people further west in Canada. :)

Hey Jo, thanks for writing about this. The Halifax Explosion is a painful part of Canadian history--the destruction, the death, on a scale that no Maritimer could ever imagine. The people of Halifax are gentle, easy-going folk and deeply mourn this event.