During the 18th century, the imperial super-powers of Europe were all in India, trying to carve it up to serve their ambitions. Poor Puducherry had once been a calm and reasonably prosperous fishing region, until the French arrived in 1673.

During the 18th century, the imperial super-powers of Europe were all in India, trying to carve it up to serve their ambitions. Poor Puducherry had once been a calm and reasonably prosperous fishing region, until the French arrived in 1673.

Since then, it had been the scene of much conflict, ranging from a brief skirmish through to full blown battles. The French had lost it to the Dutch, who had then been forced to hand back control. Now the British wanted the ports.

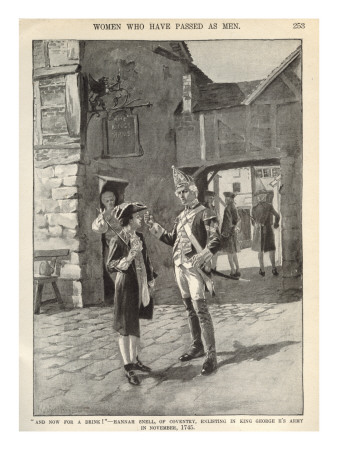

The Swallow was sent there in August 1748. The fighting was ferocious, but Hannah conducted herself with bravery and skill. The battle ended with a French win, but Hannah survived unscathed.

She wasn't so lucky at the Battle of Devicotta, aka the Seige of Devikottai, on 23rd June 1749.

There was a garrison of 5,000 people inside the fort. These weren't colonists from Europe, but local people with long historical roots in the area. Led by the Rajah of Tanjore, Pratap Singh, they were determined to not become part of anyone's Empire. They'd already repelled an earlier British invasion, just a couple of months before.

On that day in June, the scene was one of carnage. As each naval ship docked, it was bombarded by fire arrows from the fortress above. There was no way to disembark, except by rafts from ship to shoreline. All the while, death came swiftly at the hands of the defenders, inside and outside the Devi-Cottah gates.

Hannah was just one of 800 British soldiers and 1,500 sepoys (Indian soldiers pressed into service) that day. She traveled into that port and was ferried through the fire on a raft. Then, and in the fierce fighting that ensued, she was hit in the leg and groin no less than eleven times, and must have thought that her time had come to die.

She survived. Her injuries were severe, but they were treated and she was eventually carried safely away on the Swallow. The British took the fort and still no-one guessed that Hannah was female, even as she sought medical assistance.

For her valor and service, on that day and others, she would later be awarded a military pension. That was not given out lightly, and it was practically unheard of for it to be given to a woman. Hannah Snell got it though. She earned it.

Think of women in the Georgian Era and your mind wanders into a Jane Austen novel. These females are dainty in aspect and mercenary in the ways of love and marriage.

Think of women in the Georgian Era and your mind wanders into a Jane Austen novel. These females are dainty in aspect and mercenary in the ways of love and marriage.

Hannah married James Summs on January 6th 1744. The couple settled down in their own home in Wapping, close to her sister and her family.

Hannah married James Summs on January 6th 1744. The couple settled down in their own home in Wapping, close to her sister and her family.

During the 18th century, the imperial super-powers of Europe were all in India, trying to carve it up to serve their ambitions. Poor Puducherry had once been a calm and reasonably prosperous fishing region, until the French arrived in 1673.

During the 18th century, the imperial super-powers of Europe were all in India, trying to carve it up to serve their ambitions. Poor Puducherry had once been a calm and reasonably prosperous fishing region, until the French arrived in 1673.

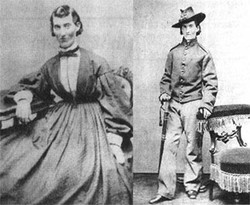

Throughout history, there have been countless examples of

Throughout history, there have been countless examples of

Hannah was an instant celebrity upon her return. The news spread out from the Portsmouth port into the rest of Britain.

Hannah was an instant celebrity upon her return. The news spread out from the Portsmouth port into the rest of Britain.

The history books are silent on why Hannah Snell moved to Berkshire. She'd run The Female Warrior for less than half a decade before she was gone. Maybe she'd made enough money to retire!

The history books are silent on why Hannah Snell moved to Berkshire. She'd run The Female Warrior for less than half a decade before she was gone. Maybe she'd made enough money to retire!

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Comments

I love hearing about women such is this one. She was living at a time, as Jo so accurately says where women were not expected to have any life or future. But women like Hannah bucked the trend.

A remarkable woman and a great example.

For some women, it was better than being at home looking after the kids and doing the housework. I don't know about Mary Walker. Perhaps I ought to read the book!

I like reading historical accounts of women doing unusual things. My sister, Carla Joinson, wrote a young adult book, "Civil War Doctor: The Story of Mary Walker", She also posed as a man.

Still it set her up for life!

No doubt....

She grew up in a military family. Her grandfather and father were both military men. Most of her siblings joined the military or married military men. I guess it was what she was raised to respect and want.

No doubt the reality proved somewhat less glorious.

Yay! I love it. I'm not sure why anyone would WANT to do that, but ya gotta follow your dreams, whatever they may be.

I thought that last was a good touch too. She must have been really good at what she did out there.

Thank you for reading.

Great Jo. I love the way you tell a story. I think it is extremely good that the Royal Navy not only pensioned her, but honored her request to be buried with other sailors.

It's horrific to think of it really, isn't it? Especially with how bloodied they must have been.